Traverse on trackUse of tractors to transport cargo, fuel back in voguePosted August 7, 2009

McMurdo to South Pole. South Pole to AGAP South. Byrd Surface Camp to Pine Island Glacier. WAIS Divide field camp to McMurdo. McMurdo to Whillans Ice Stream. Paul Thur rattles off the different combinations of possible routes that a fleet of tractors may some day make across the Antarctic continent, to shuttle cargo and fuel to remote locations in support of science. “There are a lot of traverses planned, and who knows what else people have been talking about that I haven’t even heard of,” said Thur, Traverse Operations manager for Raytheon Polar Services Co. (RPSC) The thousand-mile haul between the U.S. Antarctic Program (USAP) Other traverses, such as one planned from Byrd Surface Camp to the dynamic Pine Island Glacier, are deep in the planning stages and on the books. [See previous article: Byrd Camp resurfaces.] A few others are ideas still in need of study and development. Rolling back the clock

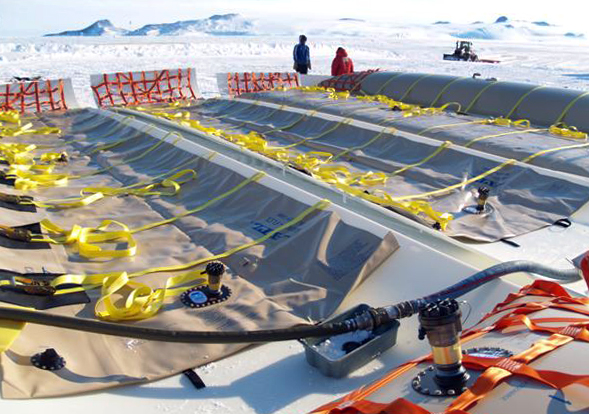

Photo Credit: Paul Thur/Antarctic Photo Library

Explosives are used to close a crevasse for safe passage of the South Pole Traverse.

“This is the way they did it before. It’s come full circle,” agreed Thur, who has made two round-trips between McMurdo and South Pole over the last two field seasons. “It’s about the same — just improved technology,” he said of today’s method of moving over snow-flattened routes by Caterpillar and Case farm tractors. “[The Navy men] got in their tractors, had all of their support gear with them, and drove as far as they could. The basic principle hasn’t changed.” The NSF sees the traverse as a cheaper, more efficient method for supplying the South Pole with fuel and materials, as well as oversized cargo that doesn’t fit in the belly of a ski-equipped LC-130. Flown by the New York Air National Guard “The introduction of heavy ski-equipped aircraft, in particular the LC-130, allowed the USAP to range widely on the continent, and caused surface traversing to fall into hibernation,” explained George Blaisdell, NSF Operations manager for the USAP. Blaisdell noted that the ski-equipped airplanes have their own limitations, such as surface roughness and sloping terrain. In fact, a Twin Otter that landed on Pine Island Ice Shelf in 2008 found the terrain too tough to return, forcing the science team to delay their plans for studying the region until a traverse can be organized next year to establish a helicopter field camp. [See previous article: Pine Island Glacier.] The aircraft limitations, “coupled with recent research interests in Antarctica needing access to access a very wide range of areas, [means] some projects are better prosecuted from a surface traverse platform,” Blaisdell said. “Thus, a revival of science traverses has occurred in the USAP.” Last year’s traverse team delivered 115,000 gallons of fuel to the South Pole, the equivalent of about 36 LC-130 flights. It costs nearly triple as much to fly cargo to South Pole on an aircraft versus hauling it overland. “The science community has been a big advocate of USAP re-developing its traversing capabilities,” Blaisdell said. “ Not only do researchers understand that logistics traverses like the McMurdo-South Pole swing produce economies with [NSF] funds, but they see that these traverse routes create new corridors of access for scientific exploration.” Driving forwardThur said the team is still learning how to maximize both the load and the speed. Last year, the tractors hauled too much, requiring the operators to shuttle cargo over steep or uneven terrain. That meant for every mile traveled, the machines actually logged three miles. It took 39 days to travel between McMurdo and South Pole, a trip Thur estimates should take 23. “We’ve got to be light and fast, and we have to average a lot better than we did this year,” he said, adding that the team will cut back on the number of fuel bladders it carries to South Pole this upcoming season. That’s because the long-term plan is to make two roundtrip deliveries each season to South Pole, each trip taking 50 days. The total traverse season is only about 110 days, so there’s little leeway in the proposed schedule. One improvement should be the switch from white- to black-colored sleds that hold the fuel bladders. Engineers with the U.S. Army Cold Regions Research and Engineering Laboratory (CRREL) “If these sleds can retain heat better, maybe we could go back up to a full 62 bladders,” Thur said. “That would be great, because we want to go as heavy as possible but still be fast.” However, next season’s schedule isn’t too tight, with only one traverse planned to South Pole, with a second, shorter trip to the base of the Leverett Glacier, which serves as the welcome mat to the polar plateau for the long-haul cargo train. On the second trip, a nine-member crew will stage and cache about 50,000 gallons of fuel for future traverses or use by scientists in the field. Meanwhile, Thur will be busy at the end of the 2009-2010 season overseeing the receipt of an entire new traverse platform on the annual re-supply vessel that visits McMurdo each January. The additional tractors, HMW sheets, living modules, fuel bladders and other equipment were purchased using about $7.5 million in stimulus money from the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act The second train should be ready to roll for the 2010-11 summer field season. Its first mission will be to widen the snow route over a short, crevasse-ridden area dubbed the Shear Zone. It will then make a trip to South Pole later in the season. To prepare for the future, Thur will sit out this year’s fieldwork. “It’s hard to let go and turn the reins over to someone else,” he conceded. “It’s exciting the first time you do it. It gets monotonous. Still, you can’t complain.” |

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsNational Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |