Deconstruction of the DomeIconic South Pole building to come down during 2009-10 seasonPosted December 11, 2009

It was never supposed to hang around this long. Ten years, maybe 15 at most. Perhaps that’s why the South Pole Dome — a modestly sized structure spanning 164 feet and topping out at about 52 feet high — has loomed so large in the lore and legacy of polar history. The final chapter in that story will be completed 35 years after the U.S. Antarctic Program’s “That means [that] icon will no longer be there, and it’s really sad to know that it’s coming down, and I won’t be there this year to be part of it,” said Jerry Marty. More on the Dome

Check back here often for more pictures on the deconstruction of the South Pole Dome.

Related Articles: ♦ Technical Details ♦ Dome FAQs A longtime Polie (as South Pole residents are called), Marty retired earlier this year from the National Science Foundation (NSF) after devoting the last 15 years of his life to the construction of the third and latest South Pole Station The new station, a two-story structure built atop stilts on a moving ice sheet, officially entered into service on Jan. 12, 2008. But even before then the geodesic dome, erected by U.S. Naval Construction Battalion 71 (the Seabees), had been relieved of duty. Civilian construction crews had finished disassembling the modular buildings under the protective aluminum shell a couple of winters ago after all operations had moved to the elevated station. More recently, the dome had been used for cold storage. Completion of a new logistics facility, an arched building near the elevated station, over this past winter means all those frozen goods now have a dedicated warehouse for storage.

Photo Credit: Forest Banks

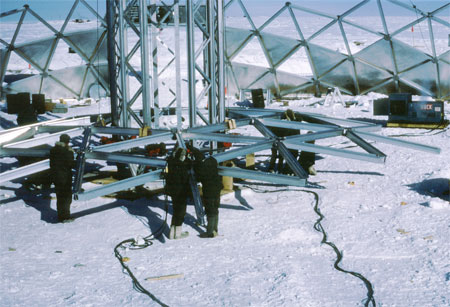

Several panels were first removed from the dome entrance to make room for work inside the building.

The dome, half buried by drifted snow and empty of everything but memories, must go as part of the South Pole long-term modernization plan. Veteran Polies like Paddy Douglas are sad to see it come down. “I have been around long enough to have lived under the dome … While the new station is grander, the old station had more character,” said Douglas, South Pole logistics supervisor. “The new station has yet to develop its own character.” Building at PoleNavy Seabees built the first South Pole Station during a frenzy of scientific activity known as the International Geophysical Year (IGY)

Photo Credit: John Perry/Antarctic Photo Library

Construction of the geodesic dome during the 1972-73 season.

Navy Seabees assembled the first South Pole Station in less than two months over the 1956-57 field season for what was to be a temporary science campaign. In reality, IGY never really ended. And no one had predicted the collection of hastily built Jamesway tents and connecting tunnels would need to last nearly 20 years. Snow quickly buried the first station, commonly referred to as Old Pole. Eventually, the crushing weight of the snow on the ice-entombed structures meant time was running out before the station would become uninhabitable. The Navy Facilities Engineering Command had determined that a new design was required for continued research by the National Science Foundation at the South Pole, according to a 1977 document published by the dome design and manufacture company, Temcor of Torrance, Calif. A dome “would be large enough to enclose and protect three buildings for quarters and operations, two of them two stories high. All these buildings were supported above the snow floor of the dome for cross ventilation,” wrote Temcor vice president Don L. Richter in the 1977 dome design document. “The dome was to offer shelter from the wind and snow, but not the cold. The need is to keep the inside temperature below 0 [degrees] F to prevent deformation of the snow support and settlement destruction of the buildings. Five vent holes were opened in the top of the dome to bleed off warm air.” Lee Mattis was the Temcor project engineer who designed the specialized erection equipment and the scheme of how to build a geodesic dome on ice. “I was the guy who said, ‘OK, here’s the dome, but here’s how we’re going to put it up,’” said Mattis, who spent two seasons at South Pole during the dome construction between 1971 and 1973. Why a dome? Mattis said a dome is a very efficient structure in terms of stability and the protection it offers from the snow. “The problem was the snow build-up [with Old Pole]. They felt if they could keep the snow off the buildings, they could extend the life, and that turned out to be true. “The dome is a unique structure. It is very strong. It has a low profile,” added Mattis, who returned to the South Pole in 2005 to advise the NSF about possible ways to bring the dome safely down.1 2 3 Next |

"News about the USAP, the Ice, and the People"

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsNational Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |