Page 2/2 - Posted May 6, 2011

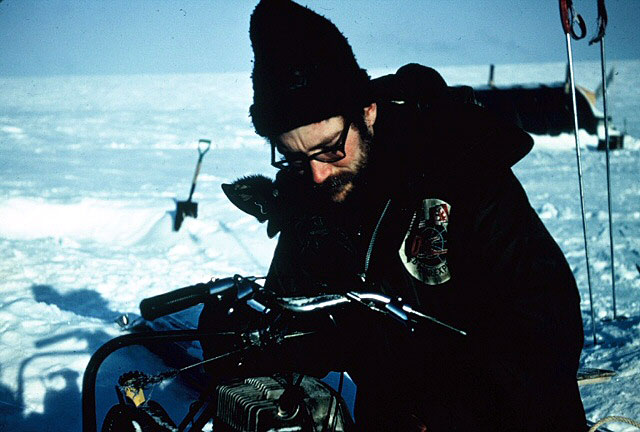

North Pole expedition was adventure of a lifetimeFour men would eventually make the final bid for the North Pole — Plaisted, navigator and radioman Gerry Pitzl, mechanic Walt Pederson, and Jean-Luc Bombardier, the nephew of Ski-Doo inventor Joseph-Armand Bombardier, whose snowmobiles the team rode to the Pole. (Aufderheide had started with the traverse team, but had later swapped places with Pitzl, because of the latter’s navigational skills.) Moriarty and several others would be at base camp at Ward Hunt Island, supporting the traverse with a Twin Otter airplane, which was often an adventure in itself. “In those days, it was much more dangerous flying up there because there were no satellite links or satellite navigation. All of the navigation was kind of dicey. It was done by sextant,” Moriarty said. It was the adventure he dreamed about — and more. But it began with some misfortune. Before reaching base camp, Moriarty had ruptured a disc in his back moving 55-gallon fuel drums, and he could hardly walk. But that didn’t stop him from joining the team shortly before the snowmobilers left on March 7. It was a sudden and chaotic departure, Moriarty recalled, as Plaisted started tossing gear into sleds and ordering the team to prepare to leave. At the same time, a storm was approaching. The pilot decided to head back to Eureka on Ellesmere Island to retrieve more fuel. “All of a sudden everyone is gone except me. I’m all alone at the base camp, and this storm came up, and it’s blowing like hell,” Moriarty said. Wind blasted through holes in the canvas covering the small Jamesway, with the temperature around minus 60 degrees Fahrenheit. Moriarty was alone for about four days. “It was pretty tough business. “We were always cold. Always cold,” he added. “I can remember getting back to Resolute Bay. They had showers. I remember walking into a building and thinking, ‘I don’t have to keep this warm anymore.’” That moment was still weeks away. Nearly two months of bitter cold, bad weather and dodgy Twin Otter missions lay ahead. The expedition members were mostly amateur adventurers — though certainly with the requisite outdoor skills — but organization was a bit on the fly, according Moriarty. “They really didn’t realize what we were getting into,” he said. For instance, the team needed to erect a 40-foot-tall radio tower for communications at the base camp. But no one had thought out how to build such a structure on ground frozen solid as rock. The MacGyver solution was to use 55-gallon drums as anchors by filling them with rocks and water, and then allowing it to freeze like an epoxy. Moriarty had the unfortunate task of climbing the tower to secure the antenna on top. “It was kind of scary,” he said. On April 19, 1968, the four snowmobilers reach 90 degrees north. Both Robert Peary and Frederick Cook had claimed the honor of being the first to reach the top of the world — Cook in 1908 and Perry in 1909. History doubts both claims, meaning the 1968 Plaisted expedition may have been the first overland traverse of any kind to the North Pole. Moriarty had gotten as close as 50 miles or so to the North Pole on a support sortie aboard the Twin Otter, but never set foot at the final destination. However, the South Pole hasn’t eluded the white-haired and lanky Minnesota native, who finally got a chance to visit the bottom of the planet this past summer after four seasons working in Antarctica. All four stints have been at McMurdo Station, the first coming in 2003-04 when he took a leave of absence from his job with the city of St. Paul, where he worked as a street light engineer for 20 years before retiring in 2009. But one suspects Moriarty is also one of those people who prefer the journey to the destination. “I just like the community down here, and I like the work, too. Of course, it’s an adventure to come down here,” he said.Back 1 2 |

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsNational Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |