|

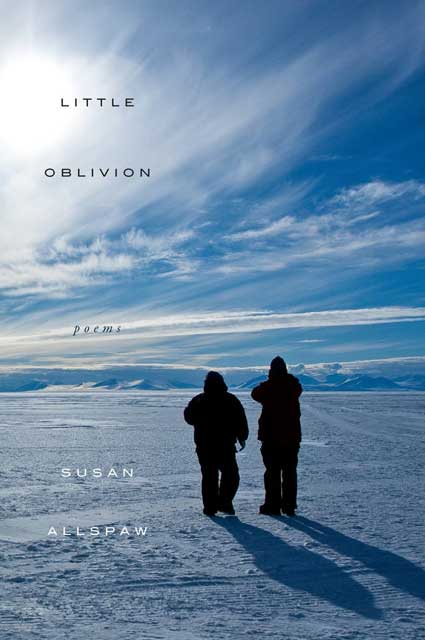

Little OblivionDebut poetry book by USAP participant a meditative love affair with AntarcticaPosted February 14, 2014

After graduating with a Masters of Fine Arts degree, Susan J. Allspaw Pomeroy That was more than a dozen years ago. Today, Pomeroy works as an information security professional for the U.S. Antarctic Program (USAP) She joins a growing number of “homegrown” USAP artists, writers and filmmakers such as Anthony Powell, whose documentary Antarctica: A Year on Ice has won numerous film festival awards, and Jason Anthony 1. What’s your history in the U.S Antarctic Program? Everyone has a story about how she or he started. What’s yours? I fell in love with the Ice before I fell in love with the man who introduced me to the Ice. … While I was in Arizona at Arizona State University Even while I took a break from the Ice and taught in Boston and Seattle for three years, I didn’t let go of the Ice in my writing. I taught a course on analytical writing that focused on Antarctic literature, and eventually found myself, and my husband, back in the program in 2003. I was even thrilled one day to walk through the lobby in our building in Centennial to see one of my former students from that class. She told me that because of that class, she, too, became obsessed with the idea of the Ice, and got a job as a dining attendant to go see it for herself. 2. How did you come to write poetry? How would you describe your style, your particular poetic aesthetic? I started writing poetry when I was around 10, but didn’t get serious about it until college. I wrote fiction throughout high school, and in college thought I wanted to pursue fiction until one semester when I took both a fiction and a poetry workshop. A snarky, yet astute student in both my classes asked me why I bothered with fiction, and I really never went back. It’s a little hard to nail down a particular style for the poetry I write, especially as I’ve moved on from the tone in a long project such as Little Oblivion. I dabble in poetic forms when the subject matter lends itself to the form – sonnet, sestina, and rondelle are some of my favorites – but I primarily write free verse. I have a background in slam poetry, so audience and sound are really important to me. I want people who read my poetry to want to read more poetry, and not think that it’s so cryptic or inaccessible. 3. Please talk about the process of putting a book of poetry together like Little Oblivion. What binds these poems together aside from being inspired by Antarctica? The book had quite a few revolutions before it found its current life. In early drafts, all it had was Antarctica, but like any good story, the main character isn’t enough to carry it. I probably wrote an additional 20 or so poems that ended up being cut from the manuscript to focus on not only the external landscape, but how that landscape is reflected in the interior of the people who work there, contractors and scientists alike, and through whose eyes the continent will always be perceived – including the limited perspective of that gaze. The progression of the intrinsic human connection to the Ice, and the way the Ice reflects our humanity back at us, became the force that drives the poems forward through the book.

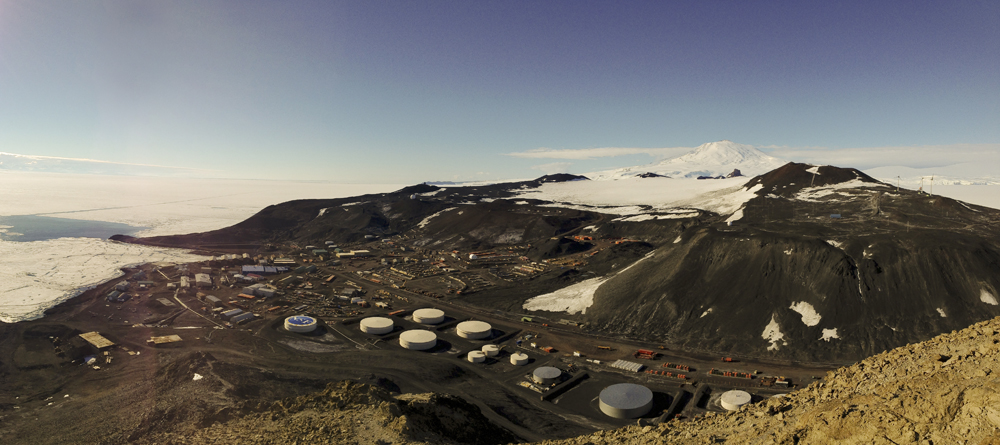

Photo Credit: Holly Gingles/Antarctic Photo Library

Riding on the research vessel NATHANIEL B. PALMER was Pomeroy's first experience in Antarctica.

At one point, I really wanted a section to focus on the early explorers – Shackleton, Scott, Amundsen, Mawson – but those poems that really focused on their histories rang too false. It felt better to let those figures be the ghosts they are, who haunt the people who are on the Ice today. When I say, “haunt,” I mean that their nature of exploration and fervor to ever excel, whether we know it or not, really does influence all of us. 4. There is a growing body of modern literature and art about Antarctica. How do you see Little Oblivion fitting into that? I’m thrilled to be included among so many amazing writers and poets who are paying attention to this forgotten landscape. Poets such as Katharine Coles, Elizabeth Bradford, and Charles Hood have brought Antarctica to life through poetry too, and I love that even among Antarctic poets, each body of work highlights a different corner of the frozen continent that we all have loved. There have even been panels in recent years at the Associated Writing Program’s Annual Conference My goal for Little Oblivion is to give readers a real sense of the internal Antarctica that everyone who has the privilege of experiencing carries with them. 5. You’re working on a new book of poetry. What’s that about? The new book, tentatively titled With Gravity, Fall, is a study on relationship and femininity, on motherhood and individualism, and the way women somehow fail but survive and thrive past those failures. That sounds pretty abstract, I imagine, so I’ll say that echoes of the internal landscape that Little Oblivion explores can be found in this new manuscript, but the images move beyond the Ice, to more down-home, domestic images, although I think this book is a bit darker than Little Oblivion. |

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsNational Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |