Photo Credit: Peter Rejcek

|

Diver Rob Robbins, left, prepares to lead Lily Simonson on a dive into McMurdo Sound. Robbins first

came to Antarctica in 1979 and has been back every year since – one of four people still working

in the U.S. Antarctic Program 35 years later.

|

Those were the days

Four USARP — er, USAP — participants recall the summer of 1979

By Jim Mastro, Special to the Sun

Posted December 12, 2014

It was called the U.S. Antarctic Research Program, or USARP, not the USAP.

Dorms 201 (the Salmon River Inn) and 202 had been completed the previous season to augment the USARP Hotel (now called Hotel California) and the Mammoth Mountain Inn.

It had only been 24 years since the U.S. Navy’s Operation Deep Freeze I, and McMurdo Station was still largely a random assortment of Jamesways (modular, cloth-covered Quonset huts), T-5s (modular wooden buildings), and metal-skinned Quonset huts. The hub of station life, known simply as Building 155, was only ten years old. The Navy was still the dominant presence.

The year was 1979.

Of the many people who stepped off a plane at the sea-ice runway or at Williams Field that year, four of them are still working here – 35 years later. For all of them, it was a year they will never forget.

Rae Spain, now in her 18th year as Lake Hoare camp manager, still remembers seeing the Royal Society mountain range for the first time. “I had no idea [Antarctica] would be that beautiful,” she says. For Julia “Jules” Uberuaga, currently a heavy equipment operator, the scene was stunning. “It was this huge, vast panorama,” she says, “like a big screen.”

Photo Credit: Jim Mastro

Rick Campbell first came to the Ice with the U.S. Navy 35 years ago. Today he helps run the USAP's traverse program.

It was decidedly less inspiring for Rob Robbins, now in his 18th year as the lead Dive Services supervisor. His first impression was that it was heavily overcast and “really cold.” When Rick Campbell, Traverse coordinator, stepped off the plane, it was a clear day, with everything white and blue. But what struck him most was the clear, fresh quality of the air. “There were no smells at all,” he recalls.

Rick had come down as a U.S. Naval Mobile Construction Battalion (SeaBee) mechanic. Rae, Jules, and Rob were all hired by the civilian contractor, Holmes & Narver Inc., as general field assistants (GFAs), which was a catch-all term for “doing whatever needed to be done.”

Rae found herself assigned as a carpenter’s helper, but that still meant being assigned a few less-desirable jobs. Rob worked out of the National Science Foundation’s administrative headquarters, the Chalet, doing anything and everything, from shoveling snow to driving heavy equipment. Jules was assigned to Williams Field, doing much the same.

Training was somewhat abbreviated in those days. Rob remembers being shown how to start a Caterpillar 944 forklift – and then being left on his own to figure out how to operate it. There were few civilians as a percentage of the total population, and jobs were also much less specialized. He could be working on a research project with a scientist one day and emptying trash bins the next.

In fact, a lot about McMurdo was learn-as-you-go. Rick calls this “McMurdo VoTech.” Jobs today are narrower in scope, but in the ’70s, people could start with one job and within a few weeks, find themselves in charge of doing several others. Though Rick started as a mechanic, he was soon driving heavy equipment, repairing utility equipment, and maintaining facilities.

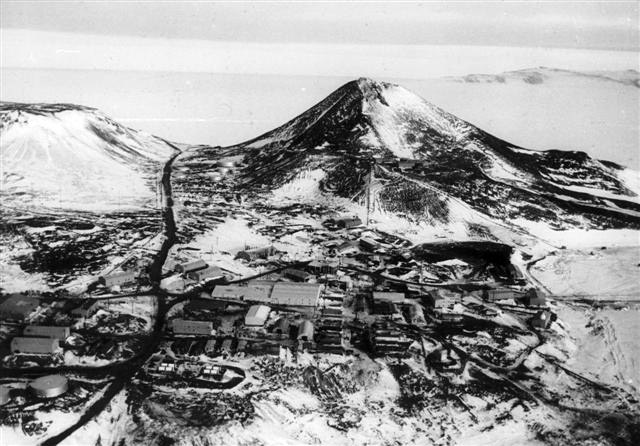

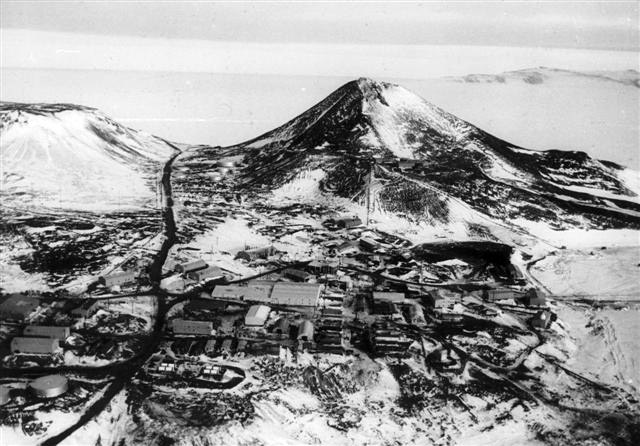

Photo Credit: K.K. Thornsley/U.S. Navy

McMurdo Station in the 1970s.

A loosely defined job structure wasn’t the only difference between now and then. According to Rae, 1979 was only the second year that H&N had hired women to work in Antarctica. Out of a total population of 913, there were only 23 women in McMurdo that year. Thirteen of them worked for H&N, while the rest were scientists or NSF employees.

It was a bit strange being such a small part of the population, and a recent part at that. (The first women arrived at McMurdo in 1969.) A few of the men groused that women didn’t belong in Antarctica, and sexism was rampant.

“It wasn’t easy,” Jules says. It was a struggle to get opportunities for advancement, especially in what were considered “non-traditional” fields for women, but, “I never felt like I wasn’t safe.” H&N also had a rule that the women weren’t allowed to have boyfriends on the Ice, but many of them did anyway.

All the women were housed on the upper floor of the relatively luxurious Mammoth Mountain Inn (though a couple, including Jules, went to South Pole for a few weeks). Most men lived in Jamesways or T-5s, both of which were distinctly down-market. Rob was one of the lucky ones housed in the USARP Hotel. Or perhaps not so lucky. Though it seemed much more upscale than the Jamesways, it was decidedly less comfortable. His room was so cold that beer consistently froze.

During that 1979-80 austral summer, there were 461 military and 147 civilian support personnel in McMurdo. All four of the ’79 alumni recalled that civilians and military personnel didn’t mingle much, but when they did, everyone seemed to get along.

Previous

1

2

Next