American ingenuityU.S. conservators help preserve history in AntarcticaPosted February 27, 2015

The stories of struggle, triumph and tragedy borne out of the adventures of men like Robert F. Scott and Ernest Shackleton have captured the imagination of many people since the early days of Antarctic exploration more than a hundred years ago. Two of the people inspired by such tales – Cricket Harbeck, an objects conservator from Milwaukee, and Julie Unruh, an art and archaeological conservator from Austin – had a hand in ensuring that part of Antarctica’s history will stand the test of time well into this century. They were among 62 specialists – including five Americans – recruited from 11 countries to conserve a trio of expedition huts on Ross Island by the New Zealand Antarctic Heritage Trust. The non-profit organization recently wrapped up a decade-long conservation effort on all three structures and more than 18,000 artifacts. [See related article — Project complete: NZAHT finishes conservation of three historic huts in Antarctica.] The huts were all built during the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration, which began at the end of the 19th century and ended in 1917 when the survivors from Shackleton’s failed Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition were rescued by the great polar explorer himself. “The idea that Antarctica was the last frontier and so little was known about it in the early 1900s, and yet all these men went down there anyway not knowing what they were getting into and not necessarily expecting to come back is incredible,” said Harbeck, who spent six months in Antarctica during the 2010-11 austral summer.

Photo Credit: NZAHT

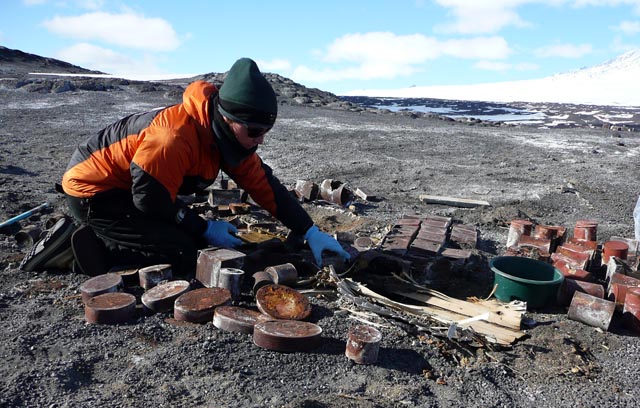

Conservator Cricket Harbeck carries out excavation at a Cape Royds food cache site.

Her job was to treat objects on site at Shackleton’s base at Cape Royds and Scott’s Hut at Cape Evans. Both expeditions involved in building the huts were scientific in nature, with the bolder and broader goal of reaching the farthest south point on the planet. Scott would reach the South Pole in 1912, but he perished from hunger and exposure with four compatriots on the journey back after losing the race to Norwegian Roald Amundsen by six weeks. There was no danger of starvation for the conservators who worked on the huts, but the long days and constant cold were just a couple of the challenges faced by Harbeck and her companions during the Southern Hemisphere summer. “What surprised me was the challenge of constant daylight, and how that played with sleep patterns and sense of time,” she recalled through an e-mail interview. “Work could be physically challenging, and sometimes it was difficult to maneuver inside the huts with all the weight and awkwardness of our gear,” she added. “You really had to move slowly and always practice self-awareness, and that was an added complexity to doing our job.” Unruh was not just fascinated with the history of Antarctica but the specific challenges it presented to conserve objects, from Antarctic’s first bicycle to boxes of moldy foodstuffs. “I was interested from the scientific viewpoint as to what happens in this environment,” said Unruh, who spent the six-month-long winter in a lab at New Zealand’s Scott Base working on objects that had been removed from the huts for treatment. “A lot of things you would worry about in other environments don’t happen here. On the other hand, strange things do happen here.” One particular problem that Unruh tackled with her fellow winter-overs involved desalinization of objects, an area of expertise that she had some experience working on from excavations in the Middle East. “The problem is that a lot of things were buried in the ground, and there are a lot of salts in the ground,” she explained, referring to the Antarctic artifacts. That’s not your typical table salt, she noted, but chemical compounds that can leach into water and make their way into porous objects stuck in the ground. When the materials dry out, the salts crystallize and can expand at extremely high pressures – hundreds or thousands of pounds per square inch. “That will just blow an object apart,” Unruh said. Much the fieldwork was a lot like archaeological conservation, according to Harbeck. “You make do with what you have, and you improvise when needed,” she said. “Though, unlike archaeological conservation, which always seems to have the constraints of resources, [Antarctic Heritage Trust] had already developed a thoughtful plan for treatment, and [we] were well provisioned.” Unruh agreed: “It’s better than some of the field labs I’ve worked in.” Originally an art historian and artist, Unruh was also drawn to the natural beauty of Antarctica. So much, in fact, that she returned to work another year in 2014-15, taking a job with the U.S. Antarctic Program as a materialsperson at McMurdo Station’s science laboratory. During the upcoming winter, she’ll work as a lab assistant at the Albert P. Crary Science and Engineering Center. “The environment is unbelievably beautiful,” she said. “I’ve never been anywhere else that looks like this. It’s just fantastic to be here.” An opportunity to go to Cape Evans earlier in the summer offered Unruh a chance to see the objects she had conserved after they had been returned to their rightful place – much changed but still the same. “A lot of the structural work they did on the building is pretty much not visible,” she said. “You have to know about it to know it happened. That’s fantastic. That means they achieved their goal of not altering the historic appearance of anything.” Other Americans who have worked on the historic huts include Josiah Wagener, Gene Wixson and Susanne Grieve. |

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsNational Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |