Thwaites Glacier – FutureScientists Work to Predict the Future of the Glacier of Greatest ConcernPosted May 17, 2021

The massive Thwaites Glacier on the coast of West Antarctica is falling to pieces because of climate change.

Photo Credit: The Polar Geospatial Center

The Thwaites Glacier is a vast expanse of ice in West Antarctica, covering an area about the size of Florida.

Shifting ocean currents are bringing warm sea water up under its vulnerable underside, melting out the ice at its base and accelerating its movement into the ocean. “Thwaites has been changing dramatically over the past three decades,” said Mathieu Morlighem, a glaciologist at the University of California, Irvine. “We have observations of that from space and also from the field, [using] many different ways of measuring what the ice sheet is doing. We know it’s not in good shape.” In response, researchers around the world are teaming up to answer fundamental questions about the glacier and better predict its future. The United States Antarctic Program (USAP) and the British Antarctic Survey (BAS) are working together, along with other international partners, to study the glacier up close like never before. Under the banner of the International Thwaites Glacier Collaboration (ITGC), the programs are bringing researchers to the remote region of Antarctica to analyze the mass of ice from the land, sea and air and use that data to predict what the glacier likely to do in the future. “If we can understand what the ice sheet is doing today, and we think we can understand what the ice sheet has done in the past, it gives us a lot more confidence in saying that we have an idea of what it will do in the future,” said Jeremy Bassis, a glaciologist at the University of Michigan. This is part three of a three-part series taking a deep look at the past, present and future of the Thwaites Glacier, its potential impact on the planet and the international effort to understand “The Glacier of Greatest Concern.” These projects are part of the International Thwaites Glacier Collaboration and are supported by the National Science Foundation, which manages the U.S. Antarctic Program, and the Natural Environment Research Council, which operates the British Antarctic Survey. The combined science effort, including meetings, discussion, outreach and supporting data, is being facilitated by the ITGC Science Coordination Office. Sea Levels RisingFor years, satellite data have shown that Thwaites Glacier is melting and speeding up as it streams into the Amundsen Sea. As more of it falls into the ocean, it releases the water that was once frozen within it and raises sea levels the world over.

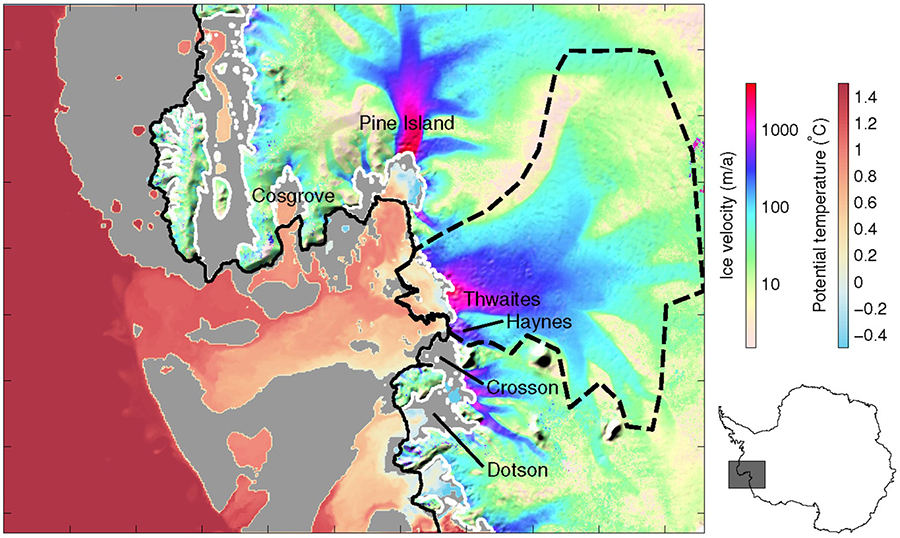

Photo Credit: Mathieu Morlighem

A combined computer model shows warm ocean water along the coast of Antarctica and the speed of glaciers flowing into the sea.

“We know at this point with pretty good certainty that sea level is going to rise. The question is how much and how fast,” Bassis said. “If we have a much better idea of how much and how fast, then we can significantly improve the ability to plan and mitigate those changes.” Though the glaciers of Antarctica are thousands of miles from the nearest city, the water they’re adding to the oceans will affect coastlines around the world. “Thwaites is huge. It holds a lot of ice, and it is changing dramatically. If we want to understand and constrain how sea level is going to change over the coming century, we need to study this glacier,” Morlighem said. “Everything that we’re learning from Thwaites can then be applied to the rest of the coast of Antarctica.” So far Thwaites Glacier has only contributed a few millimeters to sea level rise, but the Florida-sized glacier is big enough that if it completely collapses, it could raise sea levels by up to a meter, or possibly more if it takes its neighboring glaciers down with it as it goes. “Even though Thwaites is one glacier, it has a huge potential contribution to sea level rise,” Bassis said. “We would like to know what kind of contribution it’s going to make in the next century and then apply that knowledge to glaciers across Antarctica that might not be quite as sensitive as Thwaites, but once Thwaites starts to go and you go further out in the future, they could be the next tipping points.” Likely a complete collapse would take centuries. However scientists worry that because of its precarious position, its melting could speed up dramatically in the next few decades and cause serious problems the world over. Two of the teams in the International Thwaites Glacier Collaboration are working to develop computer models to predict what Thwaites is likely to look like in the future. PROPHET and LossMorlighem, along with Hilmar Gudmundsson at Northumbria University, are the principal investigators on PROPHET, short for Processes, drivers, Prediction: modeling the History and Evolution of Thwaites.

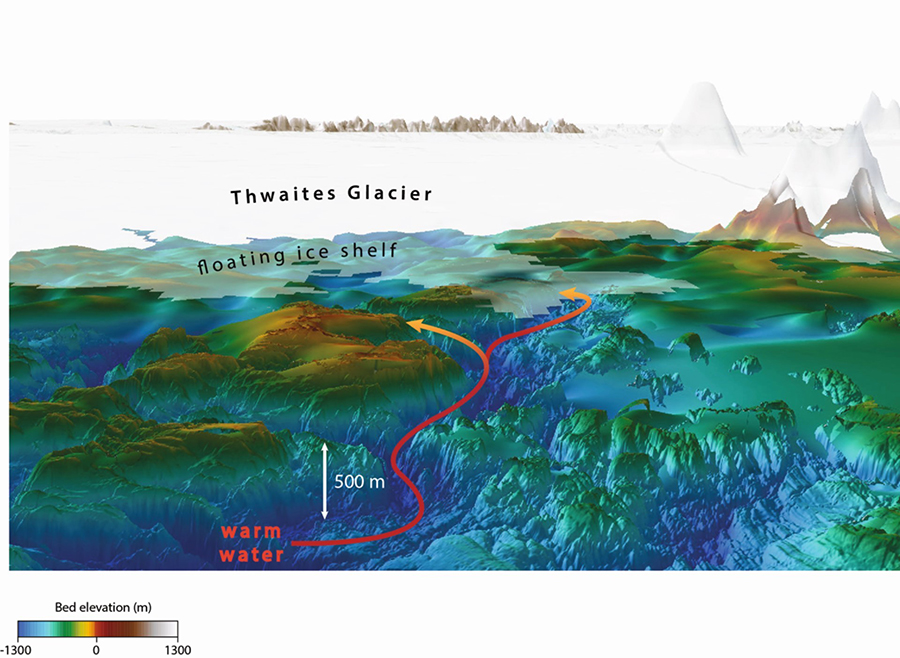

Photo Credit: The International Thwaites Glacier Collaboration

A 3D view of Antarctica looking towards Thwaites Glacier showing how warm ocean water flow up under the ice, melting it out from below.

“For PROPHET, what we’re trying to do is look at all the observations that we have, take some of the best numerical models that we have and try to improve the projections of how this glacier is going to change over the coming centuries,” Morlighem said. They’re developing computer models and simulations of the glacier to better predict overall how much of it is likely to collapse, and how soon. “We can actually already model Thwaites, we have the tools to do that,” Morlighem said. “But there are some physical processes that we would like to understand better in order for the model to be more realistic and to reduce the uncertainty in projections.” Morlighem and his team are bringing together satellite imagery along with data collected in the field by other teams in the ITGC to improve numerical models of ice flow and ocean circulation to get a more accurate simulation of the future of the glacier. “Our goal is to really tighten these uncertainties,” Morlighem said. “We’re hoping to be able to give projections that are significantly more realistic than what we can today.” There are a lot of details that only a close-up look at the glacier can capture. In particular, the team is looking to data collected in the field on what the seafloor underneath the glacier looks like. “The first thing that we need the most is seafloor bathymetry data and data of bed topography under the glacier,” Morlighem said. “It’s the geometry of these glaciers. If we don’t have the geometry right, it’s impossible to make accurate projections.” Correctly representing this bottom geometry is important because the ground that Thwaites is resting on is particularly precarious. The glacier’s grounding zone, the region where the ice first meets the ocean, is perched on bedrock along a series of ridges under the ice. Scientists worry that if the warm ocean water melts the grounding zone far enough back, it will cause the glacier to detach from the ground and dramatically increase its discharge of icebergs into the ocean. “We need to know where these ridges are, where the pathways for that warm water to reach the bottom of the ice shelf and the grounding zone,” Morlighem said. “Through ITGC, there has been a lot of data collection in that sector, so it has really been amazing.” In addition, the team is modeling the damage to the ice shelf, the thinner, floating section of the glacier that extends out into the ocean and acts as a buttress holding back the flow of the ice. “It’s not an intact block of ice; it is cracked everywhere,” Morlighem said. “The number of cracks, their size, their density, affect how much of what we call buttressing the ice shelf is producing onto the grounded ice. We can think about the ice shelf as kind of preventing the flow of the glacier from being faster.” Despite the delay in fieldwork because of the pandemic, computer-based modeling projects like PROPHET have largely been able to continue much of their work. The team is making progress developing simulations of the ice flow of the glacier and is working towards bringing together more complicated ocean models to run with the simulations. Falling Like DOMINOSOne of the least understood areas of a glacier are the tall ice cliffs that sometimes meet the sea, known as the calving front. These cliffs are the main modeling focus of the the other modeling team.

Photo Credit: Rob Larter

The high ice cliffs along Thwaites Glacier. Scientists worry that ice cliffs that are too high could crumble under their own weight, creating a cascading collapse of the glacier.

“We’re really trying to model how the ice might break,” Bassis said. Bassis, along with Doug Benn of St. Andrews University, are the principal investigators on DOMINOS, short for Disintegration of Marine Ice-sheets Using Novel Optimised Simulations. They’re using computer models to understand how tall a glacier’s cliffs can get before collapsing under their own weight. “Ice has a finite strength. As you build up cliffs taller and taller and taller, you increase the stress and eventually they’ll just disintegrate,” Bassis said. “Our part of the project is really to try and better understand if that process is likely to happen and how fast it could possibly start to disintegrate once triggered.” It’s a theorized tipping point called the “marine ice cliff instability” that scientists think might happen where a thick glacier meets the ocean. It is when the sheer front face of the glacier is so tall, and gets so heavy, that the ice strength can’t hold it and it collapses into pieces that fall into the sea. Inland glaciers and those with ice shelves sticking out into the ocean—as Thwaites currently is—are thought to be protected from this kind of collapse because of how the floating ice buttresses them. The instability arises when a sheer cliff of ice enters the ocean with nothing reinforcing its foundation. Bassis and his team want to know how tall the ice cliff has to be before the ice making up its base can’t support it anymore. “Based on observations, there aren’t any cliffs that are much higher than a kilometer from the top all the way to the bottom. It doesn’t seem like they grow too much bigger than that,” Bassis said. The real danger with Thwaites is that, if it loses its buttressing ice shelf, the marine ice cliff instability could bring about a cascade collapse of much of the ice sheet. Glaciers, including Thwaites, tend to get thicker farther upstream and away from the coast. Scientists worry that if the section abutting the ocean disintegrates, it then exposes an even bigger, more unstable cliff farther upstream, which then collapses too. This exposes another bigger cliff which then also falls into the ocean, and this disintegration continues unchecked along vast stretches of the glacier relatively quickly. “What DOMINOS really evokes is what could potentially happen, in which you line up the dominos and one starts to fall and it causes all of the rest of them to fall down,” Bassis said. A runaway collapse like that is one of the major ways that Thwaites could contribute significantly and rapidly to rising ocean levels around the world. However the marine ice cliff instability is still a theory, and no one has ever actually seen it in action. “We don’t have a modern observation that it happens,” Bassis said. “We don’t really know what really is the threshold. Is it really the kilometer, or does it kick in at two kilometers thick? Are there other things that are slowing it down? So all of these things are pretty uncertain.” To get a complete understanding of the potential instability means simulating ice on scales ranging from kilometers across to the molecular level, over timescales of just seconds to centuries. These calculations are deeply complex individually and bringing them all together increases that complexity exponentially. Ultimately, the final full simulations will take weeks or even months to run on supercomputers to get a final result. “Part of what we‘d like to do is really better understand the physical processes for it so we can have a better theoretical understanding, and then link that with all of these other observations – what [Thwaites] has done in the past, what’s the ocean doing – to try and get a better idea of whether Thwaites Glacier is likely to continue to retreat relatively slowly at a steady rate, or just to all of the sudden spectacular collapse leading to potential for large sea level rise over pretty short time scales,” Bassis said. Building these intricate models until they’re ready for the final simulation takes a long time. Over the last three years, the team has continually worked to refine their equations and compare their predictions to observations from the lab, as well as ones taken from the field. Like the PROPHET team, the DOMINOS team has been less impacted by the pandemic and largely able to continue their work. “We’re starting to get an idea of how quickly cliffs could collapse if they start to collapse, and we think we’ve got a handle on how thick the glacier has to be before it starts to collapse,” Bassis said. “There’s uncertainty in all of those things of course. The next thing to do is to try and refine that and see if we can get better constraints on it.” NSF-funded research in this story: Jeremy Bassis, University of Michigan, Award No. 1738896; Mathieu Molighem, University of California, Irvine, Award No. 1739031. |

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsNational Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |