Waves likely trigger to ice shelf break-ups and rapid disintegrationsPage 2/2 - Posted May 1, 2009

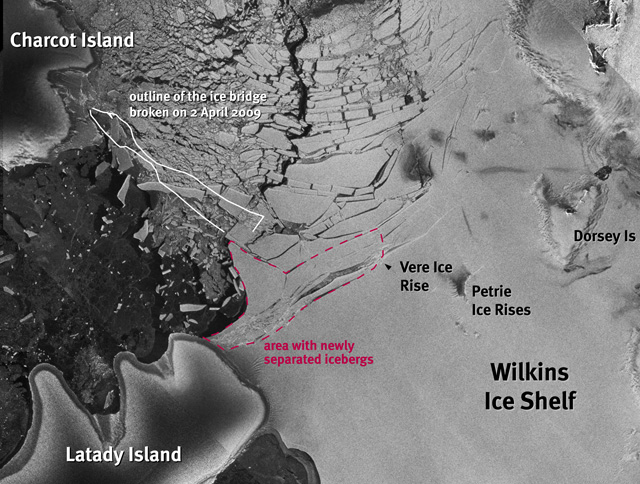

NSIDC scientists and others have previously noted that the collapse appears to be part of a pattern, and additional ice shelves in the region may be at risk. Several have retreated in the past 30 years, and at least six of them have collapsed completely — Prince Gustav Channel, Larsen Inlet, Larsen A, Wordie, Muller and the Jones ice shelves. The Larsen B has lost about three-quarters of its area, much of it in a spectacular disintegration in 2002, but a small southern patch still remains. The collapse and disappearance of these ice shelves are occurring at a historic rate, Scambos said. “They are not once-in-a-century events. They are once in several [centuries], or once in several millennia, events,” he said. The Wilkins was built over several centuries, perhaps as long as 1,500 years, he added, while the Larsen Ice Shelf at its southern extreme likely dates back well before the pyramids, more than 10,000 years. “It is climate warming that is driving the disintegrations,” Scambos explained, “driven by changes in airflow and ocean currents that are completely consistent with anthropogenic increases in greenhouse gases.” Some scientists believe the relative absence of sea ice Scambos said sea ice in the region was phenomenally low in the region of the Wilkins when the ice bridge shattered, but the latest break-up began in the center of the bridge plate and not the edges. “I’d expect that if waves were the trigger, the event would have begun at the edges,” he explained. “That is not to say that waves are not a factor in other break-up events. The shelves, when nearing their climate limit, are like racks of standing dominos — any significant stimulus, like waves, or winds, or stresses, could start a toppling runaway.” Another well-known Antarctic researcher believes it may not have been simple wave action but ocean swells from a major storm that first caused the Wilkins to break up last year. Doug MacAyeal, with the University of Chicago Distant storm waves may have been the initial trigger last year that first sent the Wilkins to pieces. “The real big waves that the surfers like, they are these long waves — these 30- to 100-second waves — that have huge wave lengths, meaning the crests will be more than a kilometer apart. Those are the waves that surfers like and the waves that ice shelves respond to the most.” Localized wave action is then responsible for the rapid break up that occurs as the ice shelf crumbles, as icebergs flip, drop and pop, creating a storm of tsunami waves that becomes self-perpetuating. As more icebergs crash about, more waves form, which causes more destruction to the ice shelf in a positive feedback loop. “The ocean became extremely rough. It was like a mosh pit of waves,” said MacAyeal, who has been studying the process of rapid disintegration for the last 10 years. What ice shelf might fall next? Scambos said that outside of the Antarctic Peninsula and the north coast of West Antarctica, the rest of the continent is responding more slowly to climate change. The South Pole is even experiencing a slight cooling trend. “So regions outside the Peninsula and Pine Island Bay are not under immediate threat,” he said. “It will continue to be the Peninsula and Pine Island [Glacier] ‘in the headlines’ for climate change for a while.”Back 1 2 |

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsNational Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |