Abundantly clearSalps appear to be gaining dominance over more nutritious krillPosted June 18, 2010

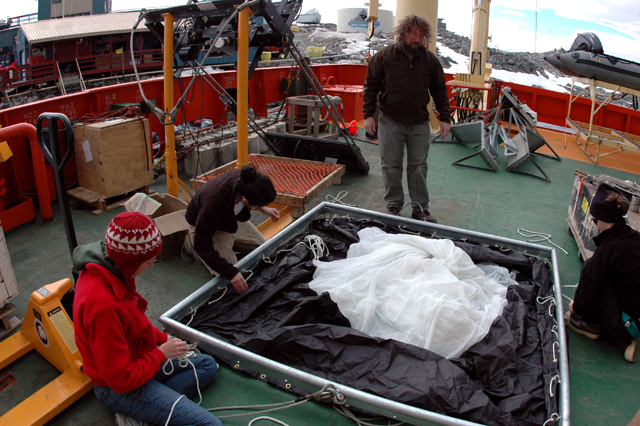

Joe Cope bellows out a rallying cry in the wet lab, causing even the gelatinous salps splayed out on a table for counting to quiver. At least it seems that way. “ZOO-OH-PLANKTON!” The mostly young group of researchers replies with hoots and hollers as they start to pick through the day’s samples with tweezers. It’s the first day of the Palmer Longer Term Ecological Research (PAL LTER) Sporting an unruly beard and a mop of curly hair, Cope looks more the role of 16th century pirate than scientist. But he is the point man on this year’s cruise for the zooplankton component of the PAL LTER program. The PAL LTER is a nearly 20-year study of the marine ecosystem off the western coast of the Antarctic Peninsula, which is one of the fastest warming places on the planet. The scientists in the program have observed extreme changes along the northern end of their research grid. Sea ice is disappearing. The composition of the food web is changing. There are several dozen species of zooplankton in this part of the Southern Ocean. One of the most important is Euphausia superba, a species of krill eaten by penguins, seals and whales. “Superba appears to be decreasing over time, and shifting closer inshore. Salpa thompsoni, on the other hand, is increasing in some parts of our study area,” said Cope, the senior technician for Debbie Steinberg’s Salps are gelatinous tunicates that filter feed in the open ocean. Their emerging dominance in some parts of the peninsula is another sign of a subantarctic climate migrating south. That trend — salps expanding their range and slipping past krill in abundance in some areas — is only one aspect of zooplankton ecology that the group is studying along a 700-kilometer-long grid that stretches from the near coast to just beyond the edge of the continental shelf. “What we’re trying to look at is how the zooplankton community is varying from north to south and from near-shore to offshore,” explained Kim Bernard, a postdoctoral researcher from South Africa with Steinberg’s lab. “It will give us an idea of what’s going to happen in the future.” Added Steinberg, who was not on the 28-day January cruise this year: “I’m really interested in all of the different groups [of zooplankton], and how they may be changing over time.” One of the newest principal investigators on the PAL LTER, Steinberg’s expertise involves studying the role zooplankton play in the cycling of nutrients in a marine ecosystem. In particular, her team is interested in how much carbon sinks out of the upper ocean into the deep as zooplankton fecal pellets. “That information is very important because it helps us figure out if a particular area is a carbon source or a carbon sink,” said Bernard, whose experiments aboard the ship included measuring how quickly the tiny marine critters digest and egest, or excrete, their food. Ironically, salps are prodigious producers of larger, faster-sinking fecal pellets, compared to krill, though most of the material found in a large sediment trap moored at the bottom of the ocean on the peninsula’s continental shelf is from the latter, according to Steinberg. But perhaps that might change with the changing population dynamics. Zooplankton, like krill and salps, represent some of the larger species in that part of the polar food web. Steinberg said her team, particularly graduate student Lori Price, is also working to characterize the tiniest species as well. “Across the world’s oceans a lot of the grazing is done by the microzooplankton, the little one-celled protozoans,” she said. “There’s very little work on that along the western Antarctic Peninsula.” Still, there is much interest in the krill as the main prey species for the megafauna. For example, Adélie penguins are particularly reliant on the shrimplike critters, especially since another prey, silverfish, has disappeared from the northern end of the Antarctic Peninsula. Steinberg’s team is working with the PAL LTER scientists studying penguins and other seabirds under Bill Fraser with the Polar Oceans Research Group. Specifically, master’s student Kate Ruck is comparing the lipid content of krill found in the north of the peninsula to those in the south, where the climate hasn’t changed. Northern penguin chicks weigh about 300 grams less than those fledged in the south, she said. “What we’re interested in seeing is if it’s the quality of the food or the quantity of the food,” said Ruck, who was also on last year’s cruise as a volunteer. “If the krill are there in the north, maybe they have a lower nutritional value.” The Southern Ocean is only the latest place where Steinberg has studied zooplankton communities. She’s worked in the North Pacific Ocean and the Atlantic Ocean off Bermuda. A recent project involves looking at zooplankton in the water plumes created by the Amazon River as it empties into the Atlantic. “It will be interesting to look at comparisons [of zooplankton] between all of these different places,” she said. “We’re already starting to do some of that. There are very different zooplankton communities in all of these different places, so it’s neat to compare them. “I look to do work in places that are interesting and relevant.” NSF-funded research in this story: Deborah Steinberg, College of William & Mary, Award No. 0823101 (includes Bill Fraser, Hugh Ducklow and Oscar Schofield). Return to main Palmer LTER story: Back in Time |

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsNational Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |