Island timeScientists pursue paleoclimate, deglaciation records from atop Roosevelt ice domePosted July 13, 2012

Roosevelt Island isn’t a place you go for vacation unless you’re really into cold and snowy places sans the après-ski amenities. Or any amenities whatsoever. Not much more than a large, icy bump on the northern edge of the nearly Texas-sized Ross Ice Shelf The study is called the Roosevelt Island Climate Evolution (RICE) project “What gives RICE, in my opinion, such remarkable potential is its location,” said Paul Mayewski

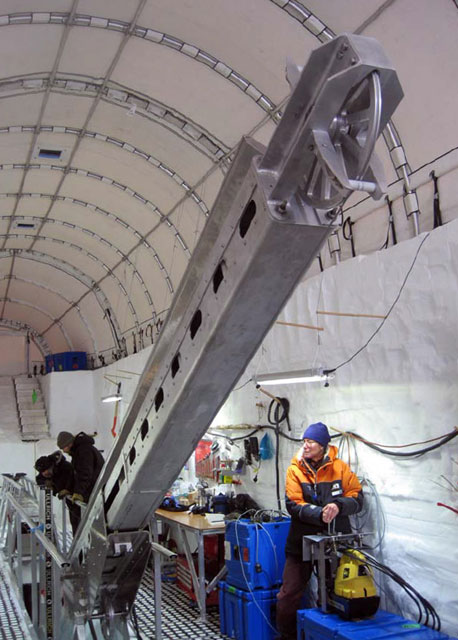

Photo Credit: Thomas Beers

Hedley Berge, Darcy Mandeno and Lou Albershardt finish an ice core drilling run and tilt the mast to retreive the core.

“It is right on the edge of an awful lot of the current climate impacting Antarctica,” he explained. “Sea ice extent has changed dramatically over the last few years. [It’s] a place where the invasion of marine air masses and the impact of the warming ocean has become very important. “It’s in a very sensitive spot,” he added. About 18,000 years ago, during the Last Glacial Maximum when ice extent in both hemispheres reached much farther than today, the Ross Ice Shelf was actually part of a much greater ice sheet. Then the world started to warm, and the ice sheet that once protruded into the Ross Sea retreated back rapidly over just a few thousands of years. The grounding line where ice meets bedrock for the West Antarctic Ice Sheet in the Ross Sea region finally stabilized about 2,000 years ago, leaving behind Antarctica’s largest ice shelf — a vital plug into which numerous glaciers and ice streams flow. Its disappearance would unleash a great deal of ice into the ocean, raising sea level and likely flooding coastal areas around the world. And there’s evidence that the Ross Ice Shelf has disintegrated numerous times in the past, with hints that it has happened even within the last million years, according to Howard “Twit” Conway “We want to understand what happened in the past so we can gain insight into what might happen in the future,” Conway explained. For this reason, glaciologists like Conway want to fine-tune the picture of ice sheet retreat that came into focus in 1999 based on his work and others, and was published in the journal Science.

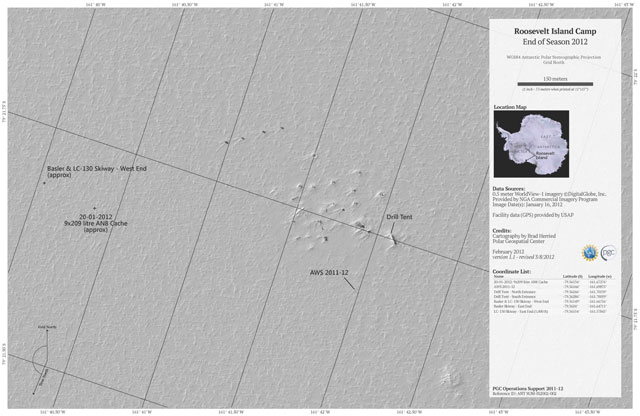

Imagery: ©DigitalGlobe Inc.; cartography by Brad Herried/Polar Geospatial Center

Satellite map of the RICE field camp on Roosevelt Island.

Conway was part of a team that first visited Roosevelt Island, a dome of ice about 100 kilometers long and 60 kilometers wide, in the late 1990s. Their measurements of ice thickness, stratigraphy, accumulation rate and other parameters allowed them to estimate the age of the ice and the thinning history of the island. That information, when combined with other data from the Ross Sea region, created a rough timeline for the deglaciation of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet. The RICE ice core will add detail to that timeline — how the ice sheet responded to past changes in climate and sea level. “We will cover a time period of dramatic change over Antarctica,” Mayewski said. “The ice core is a beautiful dipstick back in time at the northern most edge of the Antarctic continent proper.” Researchers estimate the ice core may be between 30,000 and 150,000 years old. They believe that the core will contain a high-resolution paleoclimate record that at least covers the transition from the glacial period of great ice sheets to the onset of the warming period known as an interglacial. Co-investigator Ed Brook Meanwhile, Mayewski’s lab will analyze as many as 40 different chemical elements in the ice core, which his team can use to track various atmospheric patterns that influence not only climate but ocean circulation, such as the west winds, or westerlies, which are affecting deep ocean patterns. Polar scientists believe that the strengthening of the westerlies is driving warmer ocean water onto the shallow continental shelf and thinning ice shelves that hold back glaciers that drain the interior of ice sheets. Their work will also define what an air mass known as the Amundsen Sea Low was doing over the course of those many millennia. The group is even developing methods for tracking the powerful katabatic winds that blow down from the interior of the continent. “We use chemistry as a fingerprint for the source, pathway and strength of air masses,” Mayewski explained.1 2 Next |

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsNational Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |