|

Going beyond the moviesNew e-magazine focuses on educational materials for elementary teachersPosted April 25, 2008

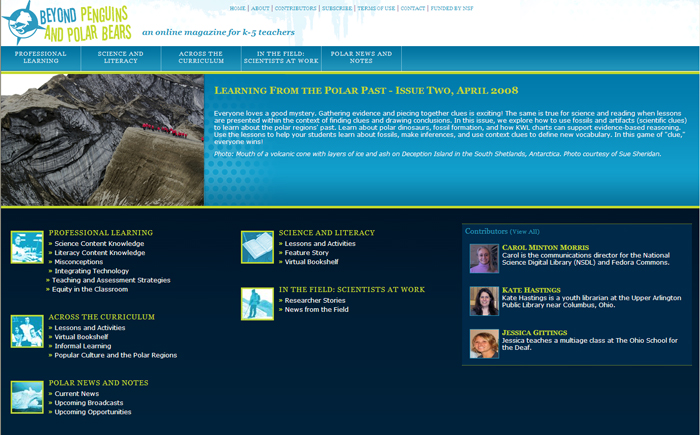

Elementary school teachers browsing the Internet for classroom inspiration on topics about Antarctica have a dizzying amount of material available. A popular Web search engine will pull up more than 39 million results. The Arctic is apparently even more popular, with some 58 million possible choices and counting. Where to start? Whom to trust? And how to fit polar science topics into an already crowded curriculum? A new online magazine focusing on the polar regions, Beyond Penguins and Polar Bears Despite a pop culture love affair with polar megafauna like polar bears, penguins and seals fanned by movies and media, elementary school curricula are generally weak when it comes to hard science, according to project collaborators. “There’s just not a whole lot out there [for polar science]. There are not a whole lot of good elementary resources on the Web for science as it is,” noted Kim Lightle, principal investigator for the project, with Ohio State University’s College of Education and Human Ecology. There are quite a few challenges for educators teaching science at these grade levels, Lightle said. The biggest: Most elementary school teachers aren’t trained in science. “That’s probably not why they got into elementary school teaching,” Lightle said. “They like the reading, and they love the kids. “If science is taught, it’s often in a disjointed way,” she added. To take advantage of the literature-centric curriculum practiced by most schools in those early grades, project collaborators designed the materials for teachers to integrate polar topics into regular lesson plans. “What we’re trying to do is the Trojan horse approach: to continue to have teachers doing what they’re very comfortable doing, which is the literacy, but have science be the core of that teaching.” Lightle and her team will produce 20 theme-oriented issues. They chose themes after reviewing elementary school curricula across the United States and identifying common topics, according to Jessica Fries-Gaither, project director of Beyond Penguins and Polar Bears, also with Ohio State University’s College of Education and Human Ecology. “So we aren’t asking elementary teachers to fit something new and extra into an already crowded curriculum,” said Fries-Gaither, a former elementary school teacher. “We’re looking for themes that they’ve already taught that would be relevant, and would be a way for us to work the polar regions into the context.” For example, an upcoming issue will focus on rocks and minerals found in the Arctic and Antarctic, to dovetail into a general lesson about geology. Each issue includes five departments: In the Field: Scientists at Work, Professional Learning, Science and Literacy, Across the Curriculum, and Polar News and Notes. The first issue of the magazine, “A Sense of Place,” introduced details about Arctic and Antarctic geography and characteristics. The feature story for “In the Field” in that issue follows Byrd Polar Research Center researcher Katy Farness and her work to image ice sheets and glaciers. Fries-Gaither said it’s particularly challenging to write and adapt material about complicated issues, such as climate change, at a level that is appropriate for the e-magazine’s audience. “The science that is going on is very high level, probably even more so than the teachers themselves care to really know about,” she said. Many of the current science resources for elementary teachers are too advanced for their classrooms, Lightle added. “We had to start from scratch in a lot of these topics that we decided to work on.” The site has attracted more than 1,500 unique visitors since it launched on March 1. Comments on the site’s blog An elementary teacher north of the U.S. border wrote, “I’m really grateful for this resource … I have been trying to encourage interest in the International Polar Year at my elementary school in Canada. This has involved an endless search for resources, current information and news updates whilst attempting to convince others of the Polar Regions’ importance and the reality of IPY! … Finding your concise and informative online publication geared toward elementary teachers and students has encouraged me to continue!” Even individual families are using the Web materials. “What a great resource! We’re a homeschooling family and I intend to make use of the material in your magazines,” read another blog comment. Lightle said the material, which includes contributions by guest writers as well as a professional science writer, also clears up misconceptions students and teachers may have about the poles. “One of the goals of this project is not to make little scientists but to keep students interested in the sciences,” she said. “We really are trying to engage kids with technology.” On the technology end of the project is the National Science Digital Library (NSDL) NSDL offered a ready-made technical platform for Beyond Penguins and Polar Bears, according to Lightle. Dean Krafft, one of the principal investigators at NSDL with Cornell University, said the online repository, with 2.2 million records, has resources that cover pre-K to graduate studies. “All of the resources were vetted by somebody, so the quality is the key component,” he explained. “It’s a one-stop shop for resources focused on science.” In fact, the online magazine follows another NSF-funded project that Lightle heads — the NSDL Middle School Portal Then IPY, a two-year science campaign concentrating on the Arctic and Antarctic, came along. Lightle and her team decided to submit a proposal based on their experience with the middle school polar-themed materials. “We’d already done a lot. We needed to bring IPY to elementary teachers.” NSF-funded researcher in this story: Kim Lightle, Ohio State University’s College of Education and Human Ecology; Dean Krafft, Cornell University, National Science Digital Library. |

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsNational Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |