Big scienceFrancis Halzen discusses decades-long quest to bring IceCube to fruitionPosted December 4, 2009

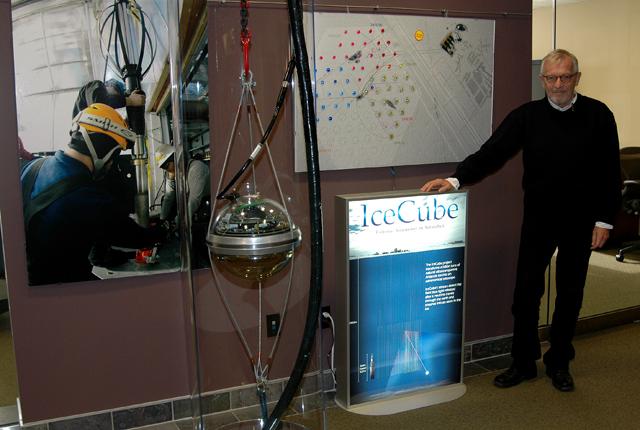

“Big science, as often as not, hinges on small moments. Once the grants have been secured and the politics navigated, the ground broken and the visionary promises made, when banks of computers flicker to life and fingers curl above keyboards, ready to flash the first discoveries via e-mail, a decade’s work can still come crashing down in the final hour – a castle erected in the thin air of theory, too weak to withstand true gravity.” — Francis Halzen, “Antarctic Dreams,” The Sciences, New York Academy of Sciences (1999) About a block from the State Capitol square in Madison, Wis., stands a nondescript office building, its façade all glass, with a noonday autumn sun glinting off the exterior. Only one business occupies the fifth floor. Cubicles crowd the interior while window-side offices ring the perimeter with a wall of glass. The hum of computers, clatter of fingers on keyboards, and hushed tones of conversation provide white noise en route to the corner office. But Francis Halzen Halzen is also no ordinary academic, even though his background is in theoretical physics, a realm of abstract reality where E=mc2 and Star Trek scriptwriters concoct warp drives and transporters. From this corner office the 65-year-old scientist leads the largest single experiment on the continent of Antarctica. Or, more accurately, in the ice itself — an altogether different telescope that when completed will span a cubic kilometer of area in the ice sheet below the geographic South Pole. Naturally, it’s called IceCube “IceCube is basically a big computer,” explains Halzen, taking a break from editing one of the dozens of scientific papers the experiment has generated, even though construction is still two years away from completion and big discoveries yet made. IceCube is really big, looking for something really small — a subatomic particle called a neutrino. The most abundant particle in the universe aside from photons (light particles), high-energy neutrinos result from violent events in the far-flung corners of the universe, such as exploding stars or by the formation of black holes. Physicists believe neutrinos contain information about such intergalactic events thanks to their ability to make a straight beeline through the universe without changing course. IceCube can help scientists trace the neutrinos back to their place of origin by capturing the incredibly brief interaction of the particles with other atoms as they speed through ice. The collision produces another particle called a muon, which leaves a trail of blue light in its wake. It’s that flash of light that IceCube captures using strings of digital optical modules (DOMs) frozen in the ice sheet. “Each module is like a satellite you launch, and it detects light. It tells you each photon it detects and when it detects it to within two nanoseconds,” Halzen says. “The rest is just a computer that collects information and makes sense out of it.” Halzen and the other 250 scientists around the world with a stake in IceCube are intensely interested in what that $272 million computer will eventually tell them about the processes that shape the universe. Even now, with only 59 of the 80 planned strings of DOMs entombed in the ice, IceCube is capturing about 100 high-energy neutrino events per day, according to Halzen. That’s an amazing rate considering the rarity of a muon occurrence. “It’s incredible what’s flowing in here,” Halzen says, waving back to the cubeland behind him where engineers and technicians hunch over computer screens.1 2 3 Next |

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsNational Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |