No bones about itScientists find traces of life without relying on the usual fossilsPosted April 8, 2011

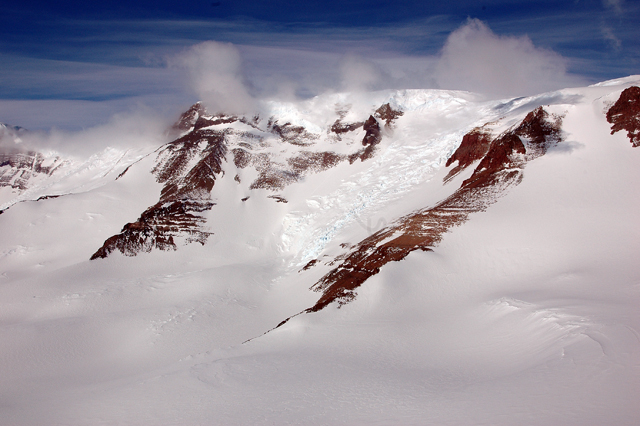

The two snowmobiles quickly turn to small specks on the white snowfield. Mountaineer Brian McCullough is in the lead, a thick rope secures his machine to one driven by scientist Stephen Hasiotis The two men are also harnessed and roped together. They’re making the first snowmobile traverse on this route to a feature called Wahl Glacier. A trail from a large field camp in the central Transantarctic Mountains had led them more than halfway, threading through a crevasse field, and up and down rises in the valley. Now they’re in virgin territory, and McCullough expertly steers to a large rock outcrop the team has dubbed “the castle” near Wahl Glacier. Hasiotis, a paleontologist from the University of Kansas Hasiotis isn’t your typical Antarctic fossil hunter. First, there’s the headgear — a worn, leather cowboy hat that stays as firmly on his pony-tailed head as Indiana Jones’ fedora. There’s also a bit of cowboy swagger in the first-generation Greek-American, as well as an infectious enthusiasm for his work. He’s quite eager to jump down onto his belly, arms and legs swinging, to illustrate how a burrowing critter that lived in a warmer Antarctica long ago might have scurried and clawed through its underground home. Hasiotis occupies a relatively rare position in the world of paleontology as an ichnologist. No, it has nothing to do with the study of fish, he admonishes, unless maybe you’re talking about the fossilized burrows left behind by lungfish tens of millions of years ago. Ichnology is the study of the “traces” created by animals, such as burrows, footprints and tracks. Hasiotis is an expert in paleoichnology, which involves trace fossils created by organisms that lived in the distant past. In the case of the team’s fieldwork in Antarctica, the period is a few tens of millions of years on either side of the Permian-Triassic boundary. That’s the time about 250 million years ago when the world’s largest extinction event occurred, wiping out about 96 percent of marine species and 70 percent of terrestrial ones. The southern continents were still stitched together in the supercontinent Gondwana. The icehouse that dominated during the end of the Carboniferous period about 300 million years ago had thawed into a greenhouse. Swamps and forests, lakes and rivers, with primitive flora and fauna, blossomed as the ice sheet and glaciers retreated. Over countless millennia this basin near the modern-day Beardmore Glacier filled with sediments as tectonic plates shifted, rifts formed and mountains rose. “Basically, we’re like a bunch of time trackers. We’re going through the pages of the past, which are these layers of sediments,” says Hasiotis, never at a loss for metaphors. Peter Flaig “So we have some idea of where the animals are living, not just what they’re leaving behind,” explains Flaig, a postdoctoral fellow from the University of Texas at Austin Re-imagining what the region was like provides clues not only to the environment at certain snapshots in time, but information about the evolution of this sector of the Transantarctic Mountains and the events surrounding the P-T boundary extinction. “If we’re really going to understand these extinction events, we need to understand how they express themselves in all different environments here,” Flaig says. On “the castle” outcrop, Hasiotis is shouting for Flaig, and a few expletives pepper his exclamations as he scrambles underneath an overhang on the castle-like outcrop near Wahl Glacier, which looks nearly sheer from this vantage point, a few bare rocks jutting out from the ice. Underneath the overhang, Hasiotis points to a smooth, rounded formation, conspicuous only to his well-trained eye among the roughly carved rocks. It’s a burrow, he says convincingly, amazed at the size. He can only guess at the critter that might have built it. Perhaps some sort of therapsid, a mammal-like reptile that flourished from 275 to 205 million years ago. They are thought to have been the precursors of mammals. |

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsNational Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |