|

Palmer Station Archives - 2017

The Start of Palmer’s Summer SeasonDecember 7, 2017

Photo Credit: Keri Nelson

Chef Mark Mican presents a side dish to Palmer Station residents gathered together to enjoy an their Thanksgiving

meal.

Photo Credit: Keri Nelson

Members of the Ducklow and Schofield research teams deploy a water sampler with Rigil's winch.

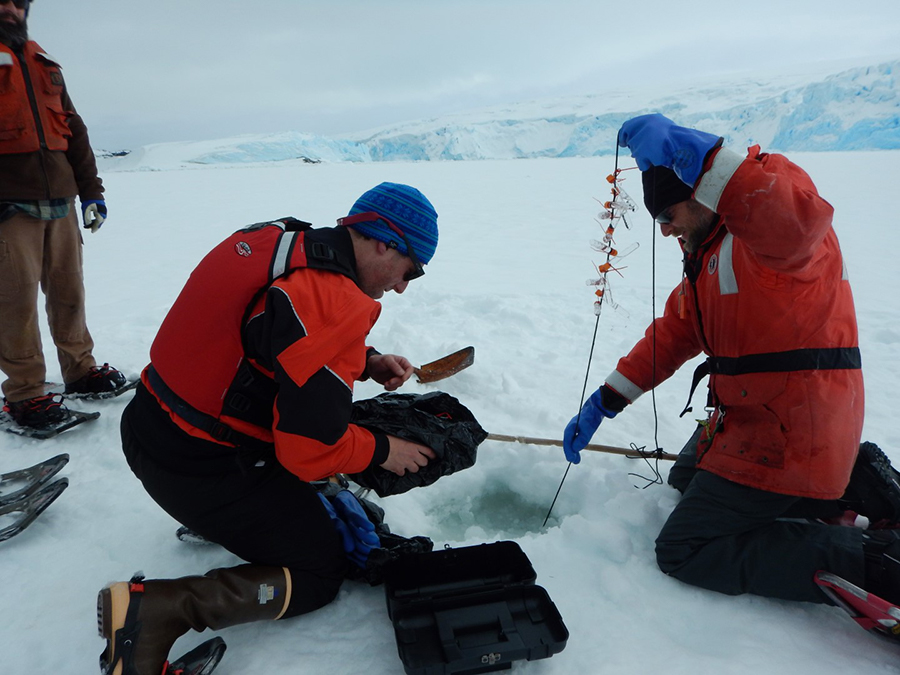

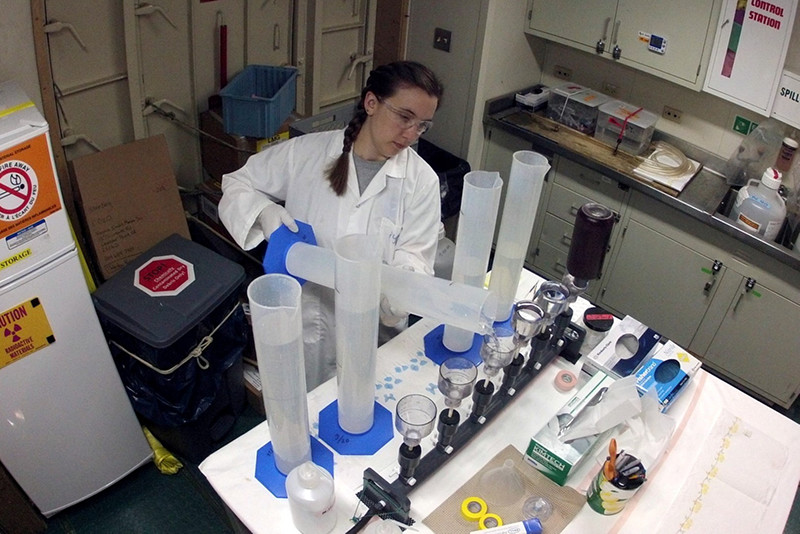

Though the researchers who arrived for Palmer Station’s science opening were at first greeted by open water, the ever-fickle ice crept back in and kept them ashore for much of November. By the middle of the month, labs set up and gear assembled, the restlessness was palpable. No one felt the pressure to get out and collect samples more than Ben Van Mooy and Jamie Collins, who were deployed for just a month to study the effects of ultraviolet-induced lipid oxidation in the Western Antarctic Peninsula. Unfortunately the abundance of ice and other issues prevented them from hitting the water. Despite hurdles, they took full advantage of their time here, sampling from the sea ice, collecting water in bottles from a zodiac, and collaborating on an experiment with the zooplankton component of the Long Term Ecological Research (LTER) Project. Ultimately the sea ice cooperated and the dedicated marine technicians were able to get three of the LTER groups out for their first sample day in mid-November. First up were the five grantees from Oscar Schofield and Hugh Ducklow’s labs, doctoral student Schuyler Nardelli and research technician Frank McQuarrie representing the former group and research technicians Marie Zahn, Emmalinna Glinskis and Anna Wright the latter. These scientists collaborate to study the phytoplankton and microbial components of Palmer LTER, respectively. After the so-called “Duckfield” team’s visits to stations B and E, seawater collected and optical instruments deployed, it was time for Debbie Steinberg’s grantees, doctoral student Jack Conroy and research technician Leigh West, to have their first foray into the field. Though Steinberg has had grantees at Palmer before, this will be the first year she has personnel on station sampling consistently for the full summer season. They will tow plankton nets from Rigil, one of the station’s new Rigid Hull Inflatable Boats, at least twice weekly in order to assess the seasonal succession of the zooplankton community and its grazing impact. They also aim to conduct experiments to identify selective feeding behavior and potential trophic cascades in the plankton food web. After the ice blew out, birders Carrie McAtee and Ben Cook from Bill Fraser’s science group have been visiting the islands near Palmer most days, surveying the local seabird populations. On their first trip, they took Chuck Kimball from the communications department along to who set up the ever-popular penguin cam for the season. Since beginning their fieldwork, they have observed Adelie penguin eggs on Humble Island, and expect that some will start to appear on Torgerson soon. November also saw the commencement of the holiday season. The Research Vessel Laurence M. Gould arrived just before Thanksgiving, bringing down grantees from Elizabeth Shadwick’s group who intended to recover a mooring. Though they were able to determine the mooring’s location, heavy sea ice prevented them from retrieving it. Fortunately, they’ll get a second chance during the LTER cruise later this summer. In preparation for the annual Thanksgiving feast, community members decked out the galley with festive adornments and, as is tradition, volunteered to bake an assortment of pies. Those back home who might pity those of us unable to spend the holidays with our families – don’t. We were well fed by our two incredible chefs, Mark Mican and KC Loosemore. After the meal, we had just enough collective energy to make it up to the lounge for the annual viewing of the movie Planes, Trains, and Automobiles. The Gould left shortly after the celebration, sending home some hardworking waste-department workers who had been on the station helping to safely dispose of unwanted refuse. We waved them off from the pier in bathing suits, huddled together for warmth, the ice having thwarted our intended polar plunge. Winter's End with Summer BeginningDecember 4, 2017

Photo Credit: KC Loosemore

A passenger on the deck of the research vessel Laurence M. Gould checks their camera en route to Palmer Station.

The journey to Palmer Station is filled with as many ups and downs —as well as side-to-side rocking—that a journey can throw at you. The Research Vessel Laurence M. Gould shuttling scientists and support staff from Punta Arenas, Chile to Palmer Station is an event that very few people have experienced. Palmer Station’s summer season starts thousands of miles away as members of the support staff converge in the Centennial, Colorado Antarctic offices for training. Everyone who passed through the offices then left for Punta Arenas. As people arrive in Chile, we are all escorted to our respective hotels. Most are within walking distance to the pier where the Laurence M. Gould research vessel (the LMG for short) is docked and ready to receive passengers. Bleary-eyed from the long flights, most people do not bother wandering Punta Arenas until the next day. Waking up to ocean scenery of Chile is incredible. Most of the next day consists of meetings and gear-issue. All of our luggage is transported from our hotel to the LMG by the time we are done and we can wander the city for the rest of the night. Since the living situation on the boat is so tight, they give you that night to prepare your room. It is infinitely harder to put sheets on a mattress when a boat is pitching back and forth, than when the boat is docked in port. Our safety meeting on the boat suggested that anything not strapped down could go flying across the room if we hit a particularly nasty wave. Final preparations were put in place and the journey across the Drake Passage was finally underway! Life on a boat can be hard for a lot of people. Many coworkers employ different strategies to combat seasickness, including a sticky band-aid medicine lovingly known as “the patch”, copious amounts of ginger tea and various nausea medicines. Some people hibernate for the four days on the boat, only getting off their bed for meals and basic necessities. Most people tend to play card games (if the waves are not too bad) or watch movies. The general consensus was that fresh air helped relieve motion sickness so I spent most of the time outside taking photos. Getting to know the crew of the LMG was a nice surprise, as well. These people who constantly traverse the Drake Passage between Chile and Antarctica are some of the most interesting people I have ever met. Usually around the third morning, we hit open ocean and most physical activities stop. Twenty-foot waves make walking between the narrow hallways or down the steep stairs hard. The best locations for this day is on a couch watching movies or in the dining room. The last morning on the boat gives you the first glimpse of the Antarctic continent. The different passages in the Antarctic Peninsula offer some incredible views of glaciers, icebergs and jagged mountains. Once past the mountains, we were treated to the first glimpses of Palmer Station. Many of the winter crew are standing outside to greet you and help with the LMG’s shoring ropes and lines. Once the newly-arrived summer crew walks off that boat, it signals an end of winter and a new beginning for the upcoming summer. Winter Wraps UpNovember 13, 2017

The rev of an engine. The scraping of metal. The thud of snow hitting pile of snow upon pile of snow. It all blended into a rhythm that became the steady drumbeat of Palmer Station in September. For every inch of snow that fell, another four blew across the Marr Ice Piedmont, gathering more from across the frozen sea ice of Arthur Harbor, and deposited en masse on our literal doorstep. Each morning dawned the same for thirty days, with a bleary-eyed army of wind-beaten and cold-weary shovelers digging anew the paths they had just excavated the day before. Ice enveloped Anvers Island as far to the horizon as could be seen, its flat white expanse punctuated only by a distant iceberg or island peak. As the days grew longer and our time on station grew shorter, more and more Palmerites ventured out to the edges of our recreational limits, but only on foot—no boat smaller than the Laurence M. Gould would be able to make it through the ice, and recreational boating had been stymied by conditions since August. For those who did make the trek to the top of the glacier, or perhaps even out to Bonaparte Point (a destination only accessible for five-and-a-half months during the winter), the rewards were wild vistas only a handful of humans had likely ever seen. Unfortunately such excursions were often hampered as bleak grey curtains of snow and torrents of wind proved to be a more common backdrop than clear skies and sunny days. Nestled between the sea of ice and the blanket of snow, Palmer station hummed on. With one month until station opening, the final 19 wintering residents were the stewards of Palmer. Though the last scientists had left at the end of August, work on station continued unabated to prepare for the new wave of personnel and projects that were only weeks away from arrival. We focused our energies on achieving both short- and long-term goals that had been reserved for completion during this researcher-less period. However, we also took time to celebrate each other and our accomplishments. With a slew of September birthdays, each week had a cause for festivity. Towards the end of the month, our ever-industrious chef prepared a feast in honor of our successes and our fortitude through the winter season. As our time on station came to a close, we had a winterover medal ceremony during which we were recognized for our service and were able to share heartfelt sentiments about our season and our comrades. As a team we faced many challenges together and overcame them all. By virtue of our successes we will leave with the contentment of knowing that we turn over Palmer to the summer crew in fine form. In just a few days the Laurence M. Gould will arrive to mark the end of our season. It is exciting to know that it will soon take us back to our friends, families, homes, and to the rest of our lives, but we will all leave a part of ourselves here at Palmer. Until we see the orange bow of the Gould break through the ice of Hero Inlet, hear that final call of “Line handlers to the pier” and wave to both new and old faces getting ready to cross the gangway, we will enjoy the last moments of the winter season and the company of our friends with whom we shared it. Gone FishingOctober 4, 2017

For some, there is a kind of inner clarity to be gained from watching ice in the ocean, one that residents at Palmer Station took to heart during July and August. Like brash floating on the surface, left to be swept to and fro, its trajectory left to the mercy of greater powers within the wind and the waves, we remained afloat through our fair share of challenges. Unlike the ice, however, we remain anchored here still. Our support vessel, the Laurence M. Gould was scheduled to arrive on July 4th, ferrying a full crew of scientists and ASC personnel allotted just under a month to work on station. However the ship was detained in port for an unanticipated additional two weeks, causing the time on station for the personnel arriving on LMG17-06 to be truncated. The Gould tied up to the Palmer Station pier on July 16th and personnel got to work as quickly as possible. On the science side, a member of the Moore science team and a representative from the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty Organization (CTBTO) for project headed straight for the Terra Lab to collect data and service equipment. The principal investigator Kristin O’Brien, arrived to close out her field team’s season and sample fish that had been in experimental treatments for up to ten weeks. Another principal investigator, John Postlethwait, arrived with his research group and field team to begin what was planned to be an eight-week field deployment with four fishing cruises. Several support staff also arrived with on board the Gould, including the program’s fire chief and fuels supervisor to inspect and observe practices, and we received a new station marine technician. Just two days after arriving at Palmer Station, the Gould set sail with five members of Postlethwait’s team to collect specimens of both white-blooded and red-blooded notothenioid fishes in Dallmann Bay and the Bransfield Strait. After a three-day fishing cruise the Gould returned to Palmer Station for a single day to offload their catch and allow the Postlethwait team to begin their experiments, and then, on July 23rd, returned to sea for a second fishing trip. While both trips were successful, the Postlethwait team found a puzzling trait in many of the icefish they brought up in their trawl. The fish have an antifreeze protein in their blood to prevent it from freezing, but a number of specimens were coming up dead with organs filled with ice crystals. Many hypotheses were offered as to why this was occurring, but the prevailing notion was that the cold sea surface temperature (over a degree colder than the temperature recorded on the bottom during collection) combined with the cold air temperature on the deck pushed the icefish over their temperature threshold—though icefish live in near-freezing waters, their antifreeze protein production cannot keep up once ice crystals begin to form in their bodies. Nevertheless, even the fish that didn’t survive did not die in vain: genetic samples and morphological measurements were taken from all fish to be used in ongoing population and physiological research. The Gould returned on July 25th, a day that quickly turned into a notable one for the season. After a fish offload and a fire drill, the phone rang with an unexpected caller – the Argentine Navy! A medical evacuation (medevac) situation had developed on an Argentine base in the South Orkneys and it was requested that the Gould be on standby for vessel support, with the possibility of departure being as soon as that evening (the Gould was originally scheduled to depart Palmer Station four days hence). Ultimately, the Gould was not needed by the Argentineans. The LMG set sail on 29 July, straight into a storm so it stayed in the lee of Brabant Island to wait out the bad weather. They wound up waiting a full week as three back-to-back storm systems passed through the Drake Passage. The various delays postponed the Gould’s return to the station. The ship made a quick port call and steamed south as fast as it could. Two days after the Gould arrived back at the station on August 15th, station scientists once again departed for a three-day fishing cruise. They were successful in finding all but one of their target species and they captured several deep-sea dragonfish of great interest to the scientists. These notothenioid fish are red-blooded but are genetically similar to the white-blooded icefish, representing a little-studied evolutionary intermediate between these two groups. Back on the station, the Postlethwait team continued their heat-challenge experiments and dissections of specimens while support staff continued to prepare for the upcoming summer season. This included several launches of Palmer’s Rigid Hull Inflatable Boat, the Rigil, including a launch and retrieval while the Gould was docked at the pier. Also on station was the safety engineer Jack Norray, who was visiting Palmer to assess and address the unique needs and challenges of Palmer Station. Compared to July, station life in August progressed rather smoothly. We weathered a few good (literal) storms, one of which caused a fender on the dock to be wrenched off its pulley on a Sunday—doesn’t Mother Nature know that’s our day off? With a great show of effort from facilities crew and station management it was secured expeditiously amidst 40 knot winds and subzero temperatures. Two days later, after the last fish specimens were sampled and the last cargo vans loaded, it was time for the Gould to depart once again. It took with it the last of the scientists for the season and leave behind the core 19 wintering crew members of Palmer Station. Many of us handled the lines for the last time on the morning of August 29th, and all of us knew that the next time we would see the Gould would be a month and a half later, on October 6th, when it would bring our summer replacements. When the Gould pulled away on a calm, clear, 6-degree Fahrenheit Tuesday morning, there was barely enough time for us to do our traditional polar plunge goodbye. The sea ice, our new constant companion, filled in the void the Gould left behind in mere minutes— a fitting metaphor for the month ahead of Palmer Station’s last resident wintering crew. Six weeks remain and much is to be done before station turnover in October. The next month will be about planning, preparing, and cleaning up, but also about making the most of our last few weeks out here on Anvers Island—remote and isolated, but the nineteen exclusive witnesses to an incredible winter in one the most beautiful places on the planet. A Month of MidwinterAugust 3, 2017

Photo Credit: Emily Olson

The sky is alight just after sunset. Palmer Station is north of the Antarctic Circle, so while it never quite

experiences a full 24 hours of darkness, the nights are long and days are short during the winter.

Winter in June? For those of us who have spent little time outside the northern hemisphere, that’s a laughable statement. However, here at Palmer Station we are finally getting a taste of winter in earnest. Every morning at 7:30 the shovel brigade heads out in the dark to clear a path, at least for as long as the snow and wind deign to keep it open. With more days than not of winds above 20 knots, that timeframe is usually not very long. As a result of the winds and the shortened daylight hours, recreational boating has been more limited this month than many would like, but on calmer days intrepid residents head out to the backyard to take advantage of the snow and sharpen their ski skills. Even though we have spent most of the past month under darkness and cloud cover, some semblance of sunlight does join us briefly for lunch before it fades back into the twilight we’ve grown to consider “day.” Midwinter, the longest night of the year, was June 21, and we relished our three hours and 43 minutes of daylight. But with a mischievous wink to the season ahead, Mother Nature’s Midwinter gift to us was snowflakes instead of a sunrise. It’s been nearly six weeks since the research vessel Laurence M. Gould last departed and 11 weeks since our last resupply. Though freshies disappeared long ago, our amazing chef, Lisa Minelli, has been keeping spirits high with meals that consistently make our friends and family back home jealous. Testament to her skill was our Midwinter celebration, in which a five-course feast including bison steak, lobster tail, and six different desserts helped us ring in the impending return of the sun. The 22 personnel and grantees on station joined together, decked out in field station finery, to enjoy this meal together. As is tradition, many Palmerites also marked the occasion with a polar plunge off the pier (reliable sources confirmed it was the coldest one yet). Another Antarctic Midwinter tradition that everyone participated in was the sending of greetings between all of the research stations on the continent. It was wonderful to see the diversity of stations that we share this unique place with, and to have a warm and welcoming connection with our fellow Antarcticans from across the world united in the pursuit of science and exploration. Never forgetting that we are all here at Palmer to ensure the success of the aforementioned goal, we continue to support the science being conducted in the labs. The O’Brien research group moves forward with their experimental study of nototheniod fish physiology undeterred and our aquarium tanks are slowly emptying of the icefish that they once held. Specimens of Notothenia coriieceps are nearing the end of their simulated stray into warmer waters; the impact of elevated environmental temperatures on their physiology will be evaluated once their 10-week acclimation period is done. Specimens of Channichthys aceratus continue to shed light on how well fish with no red blood cells can “breathe” under physical and temperature-based stress. Life on station has followed a calm and consistent rhythm over the past month that we have been left alone on our little island. Due to unforeseen complications in dry dock the Gould has been delayed at least a week and a half beyond its scheduled arrival of July 4. With no confirmed arrival date, everyone on station has been wondering when the groove we have settled into will finally end. When the Gould does return, it will bring us many new faces, but also take some old ones away—a constant cycle of life here at Palmer. Perhaps by the time we once again see the bright orange hull of the Gould pointed into Arthur Harbor, we will find the sun riding on its bow and know for sure that we are finally headed towards spring. The Last Holdout of the SunJune 14, 2017

Photo Credit: Ryan Dubina

Researchers take advantage of some rare clear weather and navigate through the ice strewn waters near the station.

We didn’t notice it until it wasn’t there: sometime, in between all of the cargo ops, food pulls, and science sampling, the sun winked at us one final time and disappeared to its winter resting place behind the Marr Ice Piedmont. Here at Palmer Station we are north of the Antarctic Circle and so are never completely without sunlight, but it is still surreal to watch a sunrise draw itself across the sky for two hours and then turn into twilight. Where do you divide dawn into dusk? Such a question might seem superfluous if you spend most of your day in a lab, but not so if your science requires time out in the field. We spent the past month cramming as much field and laboratory science as we could into the remnants of fall. On some days nature laughed at our efforts, sending us 50-knot winds, hail and four-foot ocean swells into the usually-protective Arthur Harbor. Other days dawned clear and calm, much to the delight of the Amsler/Baker/McClintock science group known collectively as the “Divers.” They used every minute of good weather to finish out their scuba diving, collecting samples of algae and benthic invertebrates for chemical analysis. They also deployed a transplant experiment, moving algae of interest from one site and depth to another site and depth. This experiment will soak in the ocean for the next year until they return in 2018 and assess whether these transplanted individuals produced different chemical compounds in their new locations. They hope this “garden” will flourish; a veritable Eden to await them when they return. In support of the Divers’ efforts, our Rigid Hull Inflatable Boat, Rigil, successfully completed its first scientific mission. After two days of waiting for a suitable weather window, and with great cooperation and assistance from multiple work centers on Station, Rigil was deployed and served as the base of operations for the diving ops on May 10. With its mission completed successfully, Rigil and its crew returned triumphant to Palmer Station and the vessel is now awaiting its next assignment in preparation for its role the ramped-up summer science season. In the labs, our aquaria were filled to the brim with fish, algae, and invertebrates. The O’Brien science group worked hard to stock up on icefish and red-blooded nototheniods to ensure that they would have a sufficient amount of specimens to last through July for their thermotolerance and hypoxia-response experiments. They also measured the oxygen consumption and cardiac output of icefish under various temperature and stimuli conditions. In the spirit of community, the O’Brien group hosted an open-house in the labs where station members could learn first-hand about the science the group was conducting, and, very lightheartedly, they also hosted a T-shirt printing night where we were able to deck out our duds with ink prints of the fish species they work with. The familiar orange hull of the research vessel Laurence M. Gould came and went regularly over the month of May to support the O’Brien science group’s fishing efforts and the Shadwick science group’s mooring recoveries along the peninsula. When it returned after each fishing trip, not only did it bring with it crates upon crates of notothenioid fish for the O’Brien group’s experiments, but also an extra 20 people to join us on station, already at maximum population size. Despite the population boom, it was great to see some fresh, friendly faces every few days. Both ship-folk and station-folk contributed to the community and culture of Palmer Station: we hosted an art show, open mic night, a crosstown dinner, weekly science lectures and a few themed parties with our vessel friends until the ship pulled away from the pier one final time on May 24. Many of our coworkers and friends who had been with the wintering crew from Day One left with it, as did all of our friends in the Amsler/Baker/McClintock group, and half of our friends in the O’Brien group. As it always is, it was sad to have to say goodbye, but as the Gould sailed around Bonaparte Point and out of view we bid them farewell in traditional Palmer fashion: with a chorus of whoops and hollers in a group polar plunge. With the station population down to just 22, the pulse of life here at Palmer has slowed and will remain steady through the Laurence M. Gould’s dry dock period in June. We look forward to this small “break,” but we also will be excited when our tether to the outside world steams back into Hero Inlet with new friends, new science and, most importantly, fresh food(!) in July. For now, we step closer every day to Midwinter and the darkest day of the year. Until then, we’ll savor the continual “golden hour” and starry nights that clear days grace us with, and learn to appreciate the strength and beauty of nature even in the storms. As the Station Turns OverMay 10, 2017

As 40-knot winds roar down from the north off the Marr Ice Piedmont and rattle the buildings of Palmer Station, it’s hard not to think back to the past few weeks of clear skies, lazy snowfalls and calm seas. We’ve had a surprisingly mild austral fall, but April has decided to go out like a lion and provide us with our first good storm of winter. Here at Palmer Station, we live under Mother Nature’s rules; sea-based field science is brings researchers here from around the world, but when the wind has its way, the Zodiacs stay on the dock, the scientists busy themselves in the lab and everyone thinks about how nice it was hiking up the glacier in the Backyard a mere 24 hours ago. Many of us are experiencing this, and Palmer as a whole, for the first time. On March 29th the ASRV Laurence M. Gould dropped off twenty-one fresh faces (and lots of fresh food) on the shores of Anvers Island. Many crossed the Gould’s gangway into Antarctica for the first time in their lives that day. Others, though, were old-hat Antarcticans returning to a place that, for whatever reason, seems to draw us back time and time again. For a week, the new winter crew interfaced with their summer counterparts and got introductions to both their jobs and their lifestyles for the next six months. Then, on April 3, the Gould set sail and we bid goodbye to the summer crew with hugs, waving arms, and quite a few chilly polar plunges off the pier. Suddenly the station was ours; a realization that brought with it some trepidation but also a station-wide sense of purpose and excitement. When the Gould left it took with it almost all of the remaining science groups that were part of the Palmer Station Long Term Ecological Research (LTER) consortium. One of those groups, headed by Bill Fraser and affectionately known as “the Birders,” left several winter personnel to continue a component of their research in their absence. These lucky “Junior Birders” boat out to Humble Island several times a week to collect data on the weights of Giant Petrel chicks, many of which, at three months old, are as large as their parents! It is a unique opportunity to have not only the chance to get up close and personal with these birds, but also to participate in important and long-running ecological research. In addition to the “Junior Birders,” Ari Friedlander’s whale biology group continues their work along the Antarctic Peninsula in support of LTER’s mission. The Amsler/Baker/McClintock science group was also joined by Bill Baker at the end of March. The “Divers,” as they are called around station, continue their research into the chemical ecology of marine organisms found in the waters around Palmer. After over a week of prohibitive weather in March, the Divers were graced with amenable conditions and returned with a bounty of study organisms for most of April. On April 19, the Gould returned with new facility and maintenance personnel and a team of riggers assigned to work on the infrastructure of our equipment around station and on outlying islands. It also delivered a new group of scientists, led by Kristin O’Brien and Lisa Crockett, here to study the physiology of Antarctic notothenioid fish under elevated temperatures. It was an active arrival, as the group brought with them three tanks full of fish that they had caught on the cruise south. Two days later they set sail on another fishing trip and returned with six full tanks of several different fish species. With all of these exciting specimens in our labs, we have filled up almost all of our aquarium space and our labs are again in full swing. The Gould also facilitated the successful retrieval of Elizabeth Shadwick’s moorings at the end of April. Finally, on April 11, we had the unique opportunity to host the passengers and crew of the RSS Ernest Shackleton when it anchored in Arthur Harbor. The Shackleton was steaming north from Rothera Station carrying a British Antarctic Survey (BAS) team headed home, some after 18 months on the Ice. We were excited to open our doors to them and give them a station tour, complete with our famous Palmer brownies. Many of our personnel talked with their BAS counterparts and exchanged knowledge and ideas about their jobs and about life on the Ice. We also had the privilege to board and tour the Shackleton. We thank BAS and the crew of the Shackleton for their hospitality and look forward to hosting them again! With all the excitement and flurry of activity over the past month, it was at times hard to stop and take it all in. It is amazing how walking outside into a pastel sunset or the sudden boom of the calving glacier are the perfect catalysts to remind you how privileged you are to be in this incomparable place. You could tell by looking at the station’s sign-out board that every opportunity to be a part of this surreal landscape, whether it be recreational boating or hiking up the glacier, was seized. As April comes to a close and both the daylight and the calm weather wane, we will look back on our first month at Palmer and know that we filled it to the brim with both work and play. But, for now, we will listen to the wind howl across our windows and the waves crash onto the rocks and know that Mother Nature has much, much more to show us before our season is through. Science and Orcas and RHIBs, Oh My!March 8, 2017

The beginning of February at Palmer Station was marked by the return of the Long Term Ecological Research (LTER) cruise on the Research Vessel Laurence M. Gould. The scientists and crew were greeted with a Super Bowl party after their month of incredibly hard work, before heading north after a hectic port call (shout out to the Palmer logistics team and the Gould’s Marine Technicians for pulling it off so smoothly!). The Gould returned to the station midway through the month for another research cruise. Research associate Liz Widen and administrative coordinator Keri Nelson hosted the last trivia night of the summer while the ship was docked at the station, bringing Palmerites and the cruise personnel together before the latter departed. During their roughly three weeks at sea, those aboard this cruise will recover a sediment trap, several moorings, two weather stations and a time-lapse camera that had been mounted to the seafloor. They will also collect glacial marine-sediment samples that will help scientists better understand the geologic history of the Western Antarctic Peninsula. Before departing, the Gould dropped off a new marine technician and the first new Rigid Hull Inflatable Boat (RHIB), named Rigil. The RHIB had its maiden voyage around Hero Inlet at the end of the month; this RHIB and a second one named Hadar will be used by the science groups starting next season. Named after stars in the Southern Hemisphere that sailors use for navigation, these boats will allow scientists to work within a 20-mile radius of station rather than being restricted to the current two-mile boating limit. The new month also brought a new science group. In February, we were joined by seven researchers from the University of Alabama and the University of South Florida. Led by principal investigators Chuck Amsler and Jim McClintock, they are here to study the chemical ecology of invertebrates and marine microalgae in the Palmer region. They have been diving as often as weather conditions permit – sometimes several times per day. The science groups already on station were met with new research opportunities and challenges alike. The whale researchers sampled five minke whales this month. No minkes have ever been biopsied at Palmer before this season, so this was an incredibly exciting accomplishment. The whalers were also able to photograph a pod of orcas that appeared within the boating limits. Like photos of humpback flukes, these orca images can be used to identify individual animals and track which regions they visit, casting light on their migration and breeding patterns, among other things. The birders stayed busy weighing and measuring the Adélie penguin fledglings on the islands around Palmer. This allows the researchers to assess the birds’ development and estimate which chicks are hearty enough survive to adulthood – 3,000 grams and under, the odds are not in their favor. The birders have also been testing some exciting new technology. With the help of whale researcher James Falbusch, Bill and Donna Fraser are repurposing store-bought photo geotaggers to track giant petrel movement for a fraction of the cost of a traditional satellite tag. The bacteria and phytoplankton LTER groups overcame a small setback this month when their CTD rosette-- a device they use to take multiple seawater samples with a single cast--malfunctioned,. Palmer’s all-star instrument technician, Carly Quisenberry and and electrician, Michael Stevenson, were able to repair it quickly, but not before the researchers got to do some old-school sampling using seven Go-Flo bottles deployed one-by-one from a winch line. We closed out February with some celebrations. The cruise ship season wrapped up late in the month as station residents visited the tourist vessel Crystal Serenity to give a presentation about the station and the science. Zee Evans, Palmer’s FMC coordinator, hosted “Open That Bottle Night” during the last weekend of the month. Station residents contributed special bottles of wine to the event which showcased the wealth of talent on station. Musicians played, people displayed their photographs, drawings, paintings, and other artistic endeavors and the chefs prepared some truly incredible hors d’oeuvres that were devoured by all. Amazingly, next month will mark the end of Palmer’s summer, with the turnover boat arriving on station at the end of March. It has been a wonderful and productive season! Cruising Through JanuaryFebruary 23, 2017

Photo Credit: Naomi Shelton

Deck hands deploy the MOCNESS plankton-catching net off the deck of the

Laurence M. Gould.

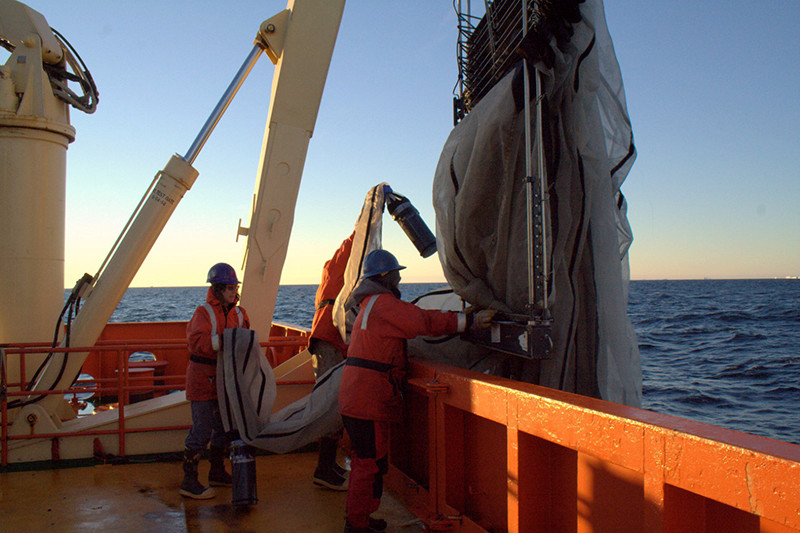

The annual Long Term Ecological Research (LTER) cruise aboard the research vessel Laurence M. Gould (LMG) kicked off at the beginning of January, bringing with it one of the season’s most hectic port calls. Over the course just two days, the cruise’s five science groups coordinated with Palmer Station personnel to transfer supplies to the ship, offload southbound cargo and complete all necessary training for first-time cruise participants. All of the Palmer LTER labs were represented on the LMG. Researchers studied bacteria, phytoplankton, zooplankton, seabird, and marine mammals during the month-long cruise. Fortunately, we also found some time to socialize with the ship folks before sending them on their way. Station residents hosted a “speed friending meet-and-greet” as well as a trivia night. After departing from Palmer, the LMG travelled along the LTER sampling grid throughout the month of January, traversing an 180,000 square kilometer area west of the Antarctic Peninsula. They visited the United Kingdom’s Rothera Research Station midway through the cruise, as is tradition, giving the whale researchers an opportunity to complete an aerial survey of the area. After departing Rothera, the cruise was able to sail farther south than they had in years, visiting Charcot Island to assess its Adélie penguin population for the first time since 2013. The seabird researchers, nicknamed “the Birders,” were productive on station as well as on the cruise, deploying several penguin satellite tags with the help of the project’s lead, Bill Fraser. The researchers leave these transmitters attached to the birds for several days at a time, collecting information about gentoo and Adélie foraging areas as well as the depth and length of their dives. These data help scientists to understand why certain penguin species may prosper while others perish in this rapidly changing region. In addition to the LTER cruise crew, the LMG’s arrival brought new a new group of people to Palmer. We were thrilled to have Polly Penhale, the National Science Foundation’s Office of Polar Programs’ Environmental Officer, visit Palmer for a couple of weeks. She was a key player in creating the Ross Sea Marine Protected Area designated last year, now the world’s largest marine reserve, and generously spoke about this during one of Palmer’s weekly science talks at the end of her stay. Two researchers studying cetaceans, a group of marine mammals including whales and dolphins, also began their field seasons this month. They focus on the Western Antarctic Peninsula’s whale population, collecting tissue samples from various individuals near Palmer. So far, they have taken samples from humpback and minke whales. They also photographed the unique patterns found on the undersides of the flukes, or tails, of each whale they see. Compiling this kind of comprehensive photo catalogue allows the researchers to recognize individual whales if they see them a second time, either in Antarctica or somewhere else along their migratory route. Some of the science groups already present on station had exciting new developments this month as well. Nicole Waite, a member of Rutgers University’s Coastal Ocean Observation Lab, deployed an underwater glider midway through the month. The glider “flew” through the waters in the Palmer Deep Canyon, its sensors measuring the waters’ salinity, temperature, chlorophyll and phytoplankton efficiency (via a FIRe fluorometer) as the instrument moved through the water column. Unfortunately, the glider sprung a leak during the last week of January and had to be retrieved before completing its mission. The group hopes to deploy a second glider for a short mission in February before the end of their season. With the departure of the LMG at the end of the month, we can look forward to some respite from the storm of logistics and science that is the LTER cruise. This will likely be short-lived, however, as we look forward to another research cruise arriving in February. Science During the HolidaysJanuary 23, 2017

Photo Credit: Leigh West

Nicole Waite bakes gingerbread houses that station residents later decorated.

December was a festive month at Palmer Station. We kicked off the holiday season by making Antarctica-themed gingerbread houses for the galley, complete with edible penguins (gentoos, Adelies and chinstraps – we don’t discriminate) and a model of the Research Vessel Laurence M. Gould. The yuletide cheer continued throughout the month – Palmerites baked cookies and made gifts for our traditional white elephant gift exchange. We were spoiled on Christmas and New Year’s Days with incredible food – seven courses, including lobster, duck, and beef tenderloin – and memorable humpback whale sightings mere meters away from Palmer’s pier. December also marked the beginning of Palmer’s cruise ship season. Multiple vessels visited us this month, with three of them bringing tour groups to station to see our facilities and sample Palmer’s famous brownies. One of these visits was part of an initiative called Homeward Bound, in which a group of 76 women with science backgrounds participate in an Antarctic expedition aimed at strengthening women’s leadership in science and policy. Midway through the month, a larger cruise ship, the Zaandam, invited Palmer personnel on board for a science lecture with a question-and-answer session. This provided a prime opportunity for station staff to share their experience with close to 2,000 tourists and to get much-needed haircuts at the ship’s salon. As with most months here, December also brought new science groups. Peter Countway, Paty Matrai, and Carlton Rauschenberg from the Bigelow Laboratory for Ocean Sciences are studying the interactions between bacteria and phytoplankton in the Western Antarctic Peninsula. Specifically, they are examining the bacterial metabolism of the organic compound dimethylsulfoniopropionate (DMSP) and how it structures the microbial community in the Southern Ocean. The team hopes that with their approach they can reveal how the DMSP cycle impacts climate. Two graduate students in Richard Lee’s lab also arrived at the beginning of the month – Drew Spacht and J.D. Gantz. They are studying the continent’s largest terrestrial animal, Belgica antarctica, a species of flightless midge common in the region. The ship on which they arrived also took J.D. to the Rosenthals, a group of islands outside Palmer’s boating limits, to collect specimens. Since the Gould’s departure, they have continued to take small boats out to other islands near Palmer several days a week. The group uses some very basic equipment, including dinner spoons, to collect specimens in the field, and then brings them back to the lab for processing. They investigate things such as the insects’ respiration as a proxy for their metabolic rate and their response to extreme environmental stressors. The Long Term Ecological Research (LTER) grantees already on station have started to observe seasonal trends. Oscar Schofield’s phytoplankton-focused group observed low chlorophyll in the water so far, which has seemed to increase with the sea ice’s retreat. Hugh Ducklow’s team has seen a generally increasing trend in bacterial production as the season progresses, indicating that the bacterial populations are growing. Additionally, with their equilibrator inlet mass spectrometer, the Ducklow group (or the “ducklings,” as they are affectionately known) have observed that the microbial community in Palmer’s waters has been alternately dominated by both primary producers like phytoplankton and animals like zooplankton. The birders have certainly had their hands full, as December has seen the birth and development of many penguin chicks in the colonies around Palmer Station, which can be seen on Palmer’s “ Penguin Cam.” The LTER groups also spent the end of December preparing for January’s LTER cruise. The Gould departs on January 5 for a month-long research cruise that, ice conditions permitting, will sample at grid station between Palmer and Charcot Island before returning. We wish them the best of luck! |

Home /

Around the Continent /

Palmer Station Archives - 2017

"News about the USAP, the Ice, and the People"

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsNational Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |