|

Water worksFormer TEA science educator returns to the Ice in support rolePosted May 31, 2013

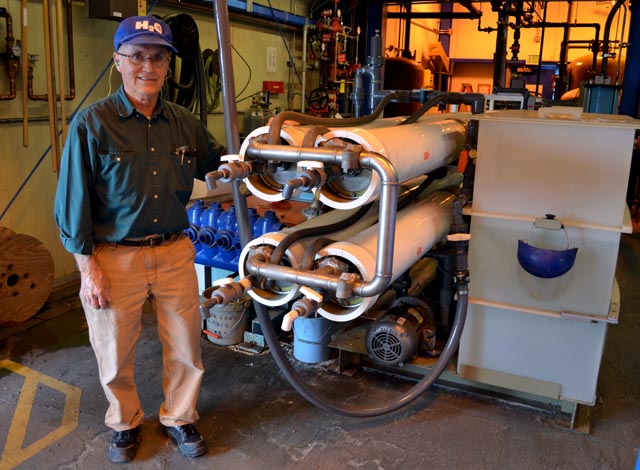

Paul Jones spent 36 years in the same high school classroom teaching science to Iowa farm kids. Every summer he would travel somewhere in the country for a field trip or participate in a program to sharpen his skills and enrich his own knowledge about the natural world. The year before his retirement took him on his most adventurous trip to date: A field assignment with scientists in the McMurdo Dry Valleys That was in 1997. Fast forward about 15 years and Jones, now 72, is back at McMurdo Station “It’s been fun coming back here,” says Jones, who first returned to the Ice in 2004 as an operator at the station’s power plant. He has also worked in McMurdo’s wastewater treatment facility. Photo Credit: Peter Rejcek/Antarctic Photo Library

A helicopter flies over McMurdo Station. At the bottom right are the power and water plants.

The career jump isn’t as far out as it sounds. Jones also spent most of those Iowa summers as a water plant operator in his hometown of Montezuma. “Teachers are always poor, and they needed help in running [the water plant],” he explains. In fact, Jones says he is licensed to work at any water or wastewater treatment plant in the state. “I doubt if there’s one person in Iowa can do that yet,” he says proudly, though he has no intentions to take over the Des Moines water plant any time soon. Jones graduated from high school in 1957, the same year that the former Soviet Union launched the first artificial satellite, Sputnik. His father bought him a portable radio that “took 10 batteries to operate” so he could tune into Sputnik’s “ominous” beeping as it circled the planet. “It really scared people,” Jones recalls. The launch — part of the so-called International Geophysical Year It also sparked Jones’ interest in science and engineering like so many young people of the era. “There’s nothing that changed science education like Sputnik,” he says. “It really got everything started.” Four years later, Jones graduated from the University of Northern Iowa “I told people that I was the head of the science department — but I was the science department,” he says. Jones may have lived his whole life in Iowa, but he hasn’t stood still. Those summer enrichment programs sent him digging for dinosaur and mammoth fossils, studying marine biology while sailing the North Atlantic and working with scientists at the National Accelerator Laboratory at Stanford University. But the most memorable was the 24 days he spent in the Dry Valleys, a relatively ice-free region near McMurdo Station. The valleys are the site of a long-term research program Jones had joined a team of researchers studying the streams that form each summer as the glaciers that terminate near the valleys’ floors melt. One of his main tasks was to eyeball under a microscope the organic material that had blown onto the glaciers and melted out into the little transient creeks. “Can you imagine: Chinese elm pollen had blown onto an Antarctic glacier,” he says. Jones’ job these days doesn’t involve studying glacial melt water but monitoring the water levels for a research station that hosts more than 900 people during the austral summer months of October through February. Seawater is pumped into the plant, which uses reverse osmosis to desalinate the water. McMurdo goes through about 40,000 gallons of water per day, according to Jones. He still employs some of his science background, monitoring the chlorine and pH levels of the water. “It’s a good job. It’s a clean, warm place,” he says. He recently got a chance to return to the McMurdo Dry Valleys during the holidays for a day trip. The place is still magical for him all these years later. “I tell people I’ve been to Mars. It’s just fantastic,” he says. |

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsNational Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |