|

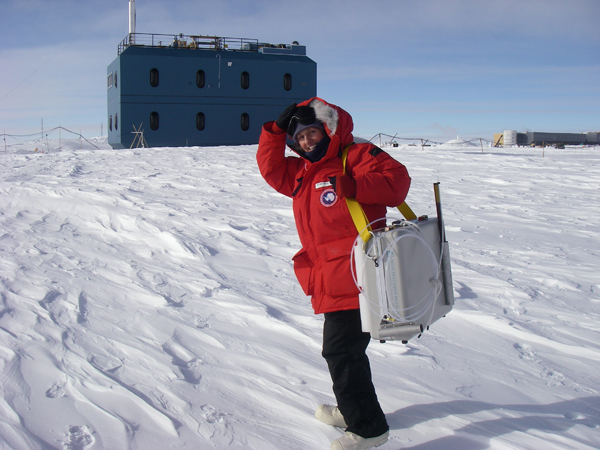

There and back againScience teacher compares visits to South Pole during different erasPosted March 14, 2008

More to the story

To read more about Elke Bergholz's work and adventures at the South Pole, check out her journal on the PolarTREC Web site

“You have gone to the South Pole twice?” students often ask in astonishment. “Why?” Yes, I have been to the bottom of the world twice in nine years as a teacher, though there are no children in Antarctica. But it has been more for me than just “having been there.” Both experiences will linger with me for the rest of my life. They have been amazing learning opportunities, not only scientifically, educationally, professionally and personally, but also historically. Being able to return to the Pole this past season brought great sense of continuity in all of these aspects. I traveled to Antarctica in 1999 as a National Science Foundation-sponsored Teachers Experiencing the Antarctic and the Arctic (TEA) educator to collect atmospheric ozone data with David Hoffman, director of what was then called the Climate Monitoring and Diagnostic Laboratory under the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration in Boulder, Colo. It was an opportunity of a lifetime for a science teacher. Imagine a second opportunity like that coming along nine years later as part of the International Polar Year (IPY). This time I headed south under the NSF-sponsored PolarTREC program, which will send 45 educators to the Arctic or Antarctic over three seasons. Both Dave and I applied, proposing each other. It was very exciting when we both heard that we were selected again as a team. PolarTREC selects teachers to experience real hands-on field science with a science team. The goal is to help reduce the gap between real field science and the science taught in the classroom. Our job was to reach out to the public and to as many students and schools as possible before, during and after deployment to the Ice. (See related story on PolarTREC: Schooled in science.) As in 1999, Bryan Johnson of the ozone group of the Global Monitoring Division of the Earth System Research Laboratory was going to work with me on the Ice. It was an unusual opportunity for a teacher to return to the South Pole and compare atmospheric ozone data from two different periods, a task usually reserved for researchers returning to the monitoring site over many years. Many students who were third-graders in 1999 were able to follow my journey again as high school students. On the Ice, my job was to learn about the science of the research team and to participate in the daily research work. I assisted NOAA team members Andy Clarke and Amy Cox with tasks like filling and launching stratospheric ozone balloons, and monitoring instruments that test for atmospheric pollutants like carbon dioxide and aerosols. Once back in the classroom, my job will be to develop class activities related to the research and to polar issues. From the South Pole, I communicated with students and the rest of the world about the research and life at the station by posting daily journals, answering e-mails and Web-posted comments, conducting video conferences, and participating in Webinars called “Live from IPY.” This trip also offered a special and rewarding opportunity of being able to compare two South Pole stations, and to be present during the dedication of the new elevated station — to be part of history. In 1999, the geodesic Dome seemed so large against the Antarctic plateau of nothingness, yet it was cozy and personable, and it was easy to interact with others. When I saw the Dome this season, I could not believe how small it was compared to the new building, which stands on stilts and is longer than a football field. With more people being there, the Pole has lost some of its intimacy. I did not understand at first why I was sad when I saw the Dome again. During my visit this past austral summer season, I often took midnight walks around the Dome, and I took photos as if to hold on to those fond memories from 1999, and to pay my private respects. But when I stepped out of the plane in December 2007 and saw the new station for the first time, I realized that it was a great manifesto to engineering and construction ability, welcoming a new century of science at the Pole. However, the new station is still small enough not to allow for any superficial encounters. The people still make the place very welcoming, with an instant offering of conversation, camaraderie or even friendship just down the hall. I found comfort and inspiration in the constant presence of so many talented people, with such different backgrounds, who were ready to share their experience at any moment, and who made me feel part of the team. The new station is incredibly comfortable, and it has all the comforts of home, including a phone in each room. All of the former facilities of the Dome are there, except larger and modern: a communications room, a medical clinic, gym, kitchen, laundry, and computer room. It has more facilities available for non-work hours, such as activity rooms for reading, playing instruments, viewing movies, playing games or doing art projects. My favorite was the “Quiet Reading Room,” which was right across from my berthing area, and boasts a wonderful collection of rare Antarctic books. And although I enjoyed the mysterious flare of the windowless geodesic Dome, sitting in the new station’s light-filled dining hall with a view of the ceremonial and geographic poles was one of the most mesmerizing encounters. On Jan. 12, 2008, we officially dedicated the new station. (See related story on the dedication: A new era.) The American flag over the old Dome was removed and placed at the new elevated station. I cannot get myself to express preference for one over the other: they each belong to such different eras. With passing of time and growing scientific projects at the Pole, we simply had outgrown the old Dome. I realized that was what made me sad: the simple fact of time passing, a fact of life that cannot be avoided. The dedication was a touching closure and tribute to “the old” and a wonderful welcome to “the new.” I felt the Dome received the respect it deserved for having served South Pole so well in its 33 years of existence. I felt very emotional during the dedication. I also felt very lucky to have witnessed the start of construction activities for the new station in 1999, and that I was able to live inside the new station nine years later. With that experience, I have become a “living memory,” to have seen both stations as a teacher. I witnessed the expansion of scientific effort at the Pole, and I can share this experience with many generations of students to come, hoping I might inspire them in one type of capacity or the other. And, above all, to spark the notion that they can follow their own dreams. “Would you go again?” another student asked me curiously. “In a blink!” I said. Elke Bergholz is a biology teacher at the United Nations International School in New York, N.Y. |

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsNational Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |