Page 2/3 - Posted September 4, 2009

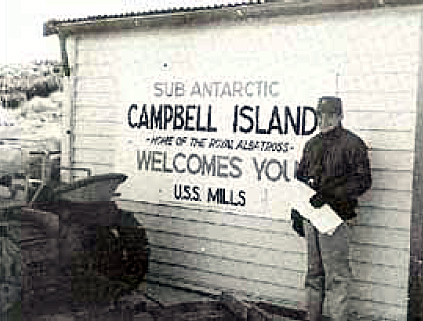

Exercise in routineThe voyage to Dunedin, NZ, took about a month. Departing Newport, we sailed for the Panama Canal. After a few days at the U.S. Navy base at Balboa, Canal Zone and a few days at Callao (Lima), Peru, we began what was to be a 20-day nonstop voyage to New Zealand. Because of rough seas along the way, the voyage took longer than planned. Calcaterra arrived at Dunedin on Sept. 21, 1965, with its fuel gauge almost on empty. After taking on supplies and fuel, we departed Dunedin four days later for the New Zealand weather station at Campbell Island. I’d soon learn that part of the ritual was to stop at Campbell Island to offload mail and supplies for the handful of New Zealand scientists who lived on the island. On the return trip, we would stop to pick up outgoing mail. On each visit, crewmembers went ashore to tour the island and enjoy a beer at the recreation center. After several hours we’d be under way again, either heading for picket duty at 60º south latitude or back to New Zealand. I would eventually learn that Deep Freeze pickets were an exercise in routine. By the end of my Deep Freeze assignment, I made a total of nine pickets aboard USS Calcaterra and USS Thomas J. Gary. During these pickets, the aerographers would send up at least two weather balloons a day and the sonarmen would make regular bathythermograph (BT) drops. The weather balloons contained a radiosonde transmitter, which sent various weather measurements back to the ship. As the balloon made its way into the upper atmosphere, the radarmen, using the SPS-8 height-finding radar, logged the balloon’s altitude and direction. The aerographers compared the radar tracks to the radiosonde data, computed the results, and sent weather reports to McMurdo Station and Christchurch. As required, the TACAN beacon would transmit navigation information for inbound and outbound aircraft. On dutyElectronics technicians did not stand under way watches, which probably annoyed those crewmembers who did. The tradeoff was that we were on call 24 hours a day to handle any failure of the radar or communication systems. During the regular workday, we would perform preventive maintenance or make routine general repairs. While on picket station aboard USS Calcaterra, I awoke one night to “Spinelli, wake up, the 10 is down.” Of course, this meant the AN/SPS-10 surface search radar was not working, and the ship was operating blind. All the SPA-8 and SPA-4 repeaters showed the same pattern of pulses that should not have been there. I’d seen this problem once before. I went to the transmitter room, where a newly minted ensign met me. Icebergs surrounded the ship, and without radar, this was not an enviable situation. The ensign was as nervous as one could imagine, and he kept asking me how long it would take to repair. I remember saying, “Ten minutes after I figure out what’s wrong.” He went to the bridge and reported to the commanding officer (CO) while I diagnosed the problem. The CO, obviously concerned by whatever the ensign told him, came down to the transmitter room and asked how long before it would be fixed. In the time it took for the nervous ensign to go to the bridge, update the CO, and for the CO to walk to the transmitter room, I had already replaced the failing part and restored the system to operation.Back 1 2 3 Next |

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsNational Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |