Stamp on historySignificant events in Antarctica reflected in polar philatelyPosted October 15, 2010

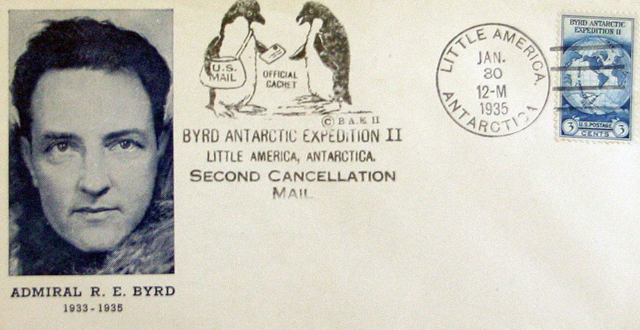

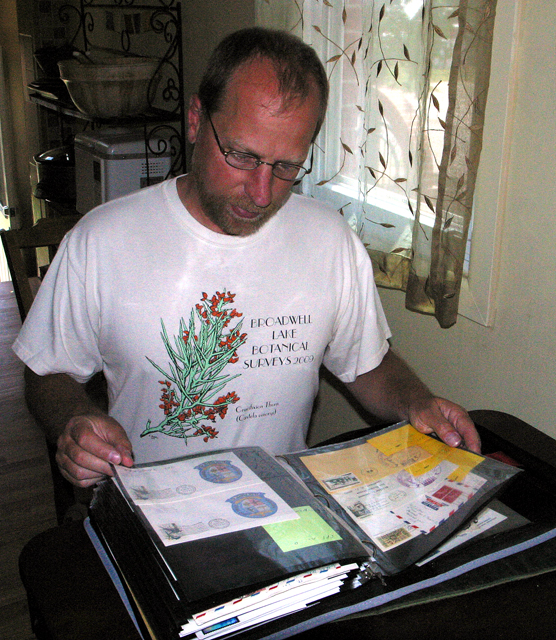

Dozens of books have been written about the history of Antarctica, many by the pivotal figures themselves, like Byrd and Shackleton and Scott. But one doesn’t have to go to the library to read the stories that shaped the continent. A different sort of narrative can be found within the zipped binders that fill the bookshelves in the basement of Scott Smith’s Denver home. Inside many are envelopes and postcards carrying addresses foreign and domestic. Some envelope covers are Spartan, with only hastily scribbled addresses. Others are stamped with penguins or show printed artwork from different expeditions or military-sponsored operations, called cachets. The canceled marks over the stamps pinpoint not just a date in time but also a moment in the historical development of a continent. “All of these envelopes have a history attached to them. They tell you a story,” said Smith, who for nearly 20 years worked for the U.S. Antarctic Program (USAP) The postal history of the continent dates back to at least the 1800s with the early expeditions, represented by the first U.S. mission led by Charles Wilkes from 1838-1842, according to Hal Vogel, a polar philatelist for more than 50 years. One archival piece of mail includes a letter from Wilkes, a naval officer and allegedly the inspiration for Moby Dick’s Captain Ahab, to his wife informing her he was returning to the States. “[The letter] took so long to get home that he was already home when it arrived,” said Vogel, who has penned a number of publications and is a member of one of the world’s leading polar philatelic societies, the American Society of Polar Philatelists Vogel recalled seeing the famed scientist Paul Siple on TV one Sunday morning in the mid-1950s as a young boy. Siple was discussing how he would work at a research base at the South Pole. Already a budding philatelist, Vogel reckoned he could send a letter to Siple and receive a South Pole cancel in return. About two years later, he got the canceled letter back. Over the last 50 years, he’s become an expert in polar philately, winning numerous awards at philatelic exhibitions with his collection. He seems to possess an almost encyclopedic knowledge of Arctic and Antarctic history by following the postal trail through time. “These items postally document an event, an individual, an occurrence. It’s almost like a time stamping of history,” Vogel said. “There are pieces of polar postal history that are the only ways that we know of certain facts.” For example, a man named Morrison, a Maori (native) from New Zealand, sent several letters home to his mother during Adm. Richard E. Byrd’s first Antarctic expedition (1928-30). But there’s no reference to the man in the expedition’s official record, Vogel said. “Even in Byrd’s narrative he doesn’t exist. The only way to know that he exists is this mail to and from him,” Vogel said. “It is on expedition stationary or has expedition cachets, or it is canceled wherever he was. We know this individual is on this expedition. We wouldn’t have known it if it wasn’t for his mail.” Smith caught the philatelic bug about 40 years after Vogel. An article on polar philately spurred him to collect the various combinations of U.S.-related covers and cancels from the beginning of the International Geophysical Year (IGY) “I thought, ‘How many could there be?’ I figured 50 cancels, 50 envelopes. It would be complete. Not even close,” Smith said ruefully. Try almost 400 cancels — four hundred different cancellations from various research stations, particularly McMurdo and South Pole, but also bygone scientific bases like Byrd and Little America V. And for nearly 40 years the U.S. Navy mostly ran the logistics show, meaning all the ships that went down to the Ice had their own post offices for the sailors, according to Smith.1 2 Next |

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsNational Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |