Page 3/3 - Posted July 18, 2014

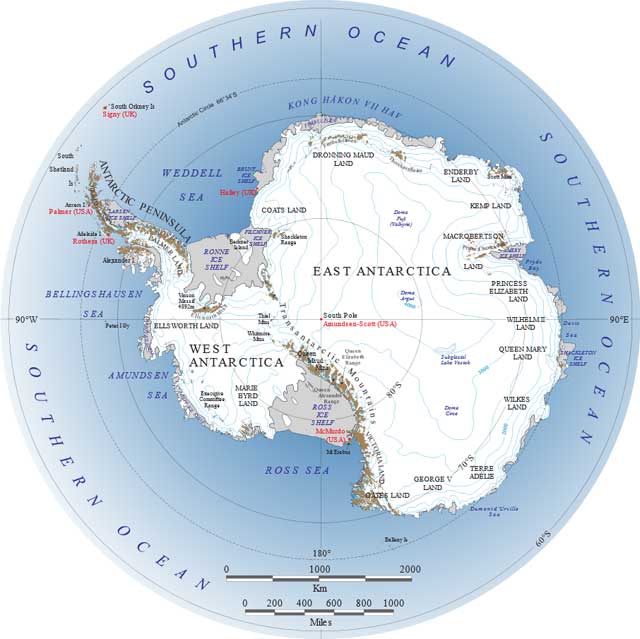

Tightening the rulesThere are some names that will likely never be attached to a glacier or mountain peak, based on the U.S. rules. Inappropriate nomenclature includes contributors of funds, equipment and supplies, as well as the names of products. The names of pets and sled dogs – the latter of which the British have used on a limited basis – are also mostly nonnegotiable. The British made an exception when its place-names committee named a cluster of features near Rothera Station after sledge dogs and dog teams. This was an exceptional event to recognize the half-century contribution of dogs to Antarctic science and logistics, from 1946-1994, according to Fox. Like with U.S. policy, common use also played a role in the decision. “It was also because these features had locally evolved the names, and they had become a well-established part of the lore of Rothera Station Nations tend to work cooperatively over naming protocols and find common ground, according to Borg. Countries are also inclined to restrict their efforts to geographic areas where they are located or work. For example, the British concentrate their efforts around the Antarctic Peninsula region where most of their research bases are located. Scientists from the University of Minnesota participated in a series of expeditions in the early 1960s across the southern half of the Ellsworth Mountains. The range became known as the Heritage Range because many of the named features within revolved around an American theme. “I’m in favor of keeping [the rules] tight, so if it’s a feature … you really have to earn it,” said John Splettstoesser Splettstoesser said he is concerned that some nations may apply names to features in regions where they have no particular interest – geographic, historical, scientific or otherwise. Bulgaria has added dozen of names in the Sentinel Range of the Ellsworth Mountains, he noted. “I raised the alarm … about this example of ‘saturation naming’ for several reasons,” he said. “I think this is something that should not be taken lightly.” [See related article — What's in a name? No international guidelines exist for national committees on geographic features.] More places to nameThe language used within each nation’s individual naming authority guidelines can sound quite similar. Bulgaria’s toponymic guidelines “Indeed, the U.S. place-naming effort in Antarctica has always been exemplary, probably the best among all Antarctic nations,” Ivanov said via e-mail. As of January 2014, there were 1,159 Antarctic place names in the Bulgarian Antarctic Gazetteer Ivanov agreed that in one sense the Antarctic has reached the end of an era in terms of the sort of exploration that once earned men the honors of glaciers and mountain ranges. But there are still plenty of blank areas left on the maps to name. “My 20-year experience in Antarctic place naming would rather suggest that there are thousands or more of notable second- or third-order features for naming (not counting subglacial or submarine features),” he said. “This may become increasingly apparent with the ongoing improvement in the available satellite imagery (notably Google Earth) and high-precision topographic mapping,” he added. “Therefore, the Antarctic place naming is probably lagging behind practical demands nowadays, and in need of a more dynamic approach.” Tourism changes the gameTourism is also driving a need to put a name with a previously unnamed feature, according to Fox. More than 37,000 tourists visited the Antarctic in 2013-14, according to the International Association of Antarctica Tour Operators “Adventure tourism ships and their small boats are venturing into areas not used by logistics ships en route to research stations, and there are also increasing numbers of yacht-borne mountaineering expeditions climbing unnamed peaks,” Fox noted. “It is important for the [place-names committee] to apply appropriate names to these new features so that unofficial, colloquial names do not come into general use by tourist groups,” he added. Splettstoesser said “approved” tourism visits are generally to areas already named, on maps, charts and gazetteers. “Tour operators are not eager about finding new places of interest, whether for wildlife presence or other reasons, partly because the routine locations have been proved by operators for safe visits, environmentally without disturbance to wildlife (fauna and flora), and also do not pose safety risks associated with terrain or glacier travel,” he said. A lecturer and naturalist on more than 100 tourist cruises to the Antarctic since 1983, Splettstoesser has supported naming features after several people who were instrumental in the tourism industry. That includes Lars-Eric Lindblad, who operated the first cruise to Antarctica in 1966 and pioneered expedition tourism as a means of environmental awareness. The tourism boom, however, also underscores the argument made by the U.S. names committee in updating its rules. “It’s just not the remote part of the world that it was in the ’60s,” Borg said. |

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsNational Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |