Change of plansStiff sea ice forces LARISSA science cruise to reassess project prioritiesPosted January 15, 2010

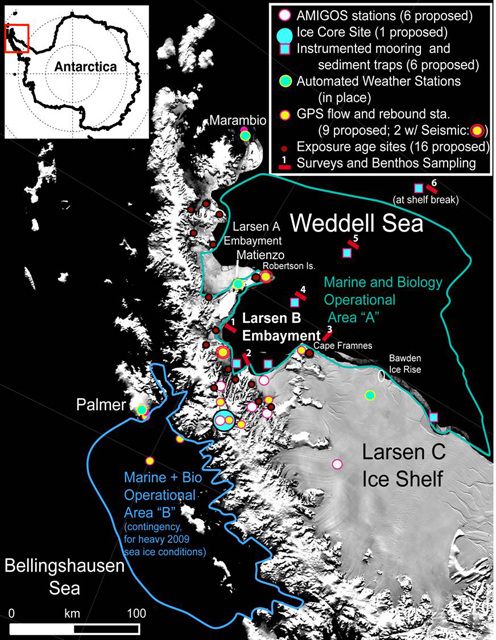

The bitter cold and snow that gripped much of the United States and Europe in early January wasn’t the only weird weather in the world that caused widespread disruptions in operations. On the flip side of the equator, scientists and support personnel aboard a U.S. icebreaker encountered unusually thick summer sea ice in the Weddell Sea as they attempted to push south along the eastern edge of the Antarctic Peninsula. The RVIB Nathaniel B. Palmer Scientists aboard the National Science Foundation They want to look at the marine ecosystem, particularly a previously discovered cold seep community, which subsists not on light as most ecosystems but on methane vented through the seafloor. They’re also interested in how the biology is changing since the ice shelf disappeared. Other researchers will take sediment cores from the seafloor that will tell them something about the mechanisms and processes behind the collapse, as well as details about the region’s past climate by looking at the layers of sediments. Above the water, scientists will fly by helicopter to glaciers to set up instruments around the ice to understand how it flows and changes. The helicopters will also take them to areas of exposed rock on the peninsula to collect samples that they can date to determine the timing of glacial retreat. That was the plan until the sea ice. After several days of trying to find a route farther south — including an air reconnaissance mission by helicopter — the Palmer retreated on Jan. 12, steaming to the western side of the peninsula where sea ice is virtually nonexistent this far north. It entered the Gerlache Strait, not far from the U.S. Antarctic Program’s Palmer Station A helicopter from the ship arrived the following day, landing in the rocky “backyard” behind Palmer Station where a glacier once sat before things warmed up here. It carried Maria Vernet Working with Palmer Station research associate Brian Nelson at the TerraLab science building, Vernet scrolled through various meteorological maps and composite satellite images, looking for whatever data the team might be able to use to determine when a break in the sea ice might occur. “The more we can plan ahead the better,” she said, adding that the best-case scenario would involve a powerful storm that could blow out the sea ice. “We’re looking for bad weather,” she said. “I never expected to ask for bad weather, but there’s always something new whenever you come down here.” What the crew and scientists would probably like to see is the sort of gale force winds that buffeted the ship through the Drake Passage on its transit south from Punta Arenas, Chile. The gusts peaked at 101 knots, or 115 miles per hour, for a day, sending most people to their bunks to wait out the storm. Unfortunately, a high-pressure system had settled right over their target area in the Weddell Sea and didn’t seem inclined to budge any time soon. Though the Palmer is an icebreaker, the sea ice is too extensive to attempt an entry. On Jan. 14, the ship had settled into Flanders Bay in the Gerlache Strait, where the helicopters could conceivably fly across the peninsula from west to east to four of the five sites targeted by glaciologists. Ted Scambos The Palmer pulled into Arthur Harbor the next day, Jan. 15, and the station sent a Zodiac boat out to retrieve several scientists who wanted to do some quick online research about possible work they could do in some of the nearby fjords on the western side of the peninsula. “We didn’t expect to be here,” said Michael McCormick, associate professor of biology at Hamilton College Another team of LARISSA scientists is working independently from the Palmer, drilling an ice core from a field camp based on the 2,000-meter-high Bruce Plateau. Vernet said that team is having great success, having collected 270 meters of ice as of mid-January. Researchers can study the chemistry of the atmospheric gases trapped in the ice, as well as other properties such as dust particles, to reconstruct past climate. [See the team's blog Vernet said the LARISSA team hopes to return to the eastern side of the peninsula by early February if not sooner to conduct the biological and sedimentological experiments for the project. The ship is expected back in port by the first week in March. “We’re still working on a plan,” she said before boarding the Bell helicopter back to the Palmer. “We’ll get what we can get down from here. Many of us have worked down here before, so we know not everything goes according to plan.”

|

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsNational Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |