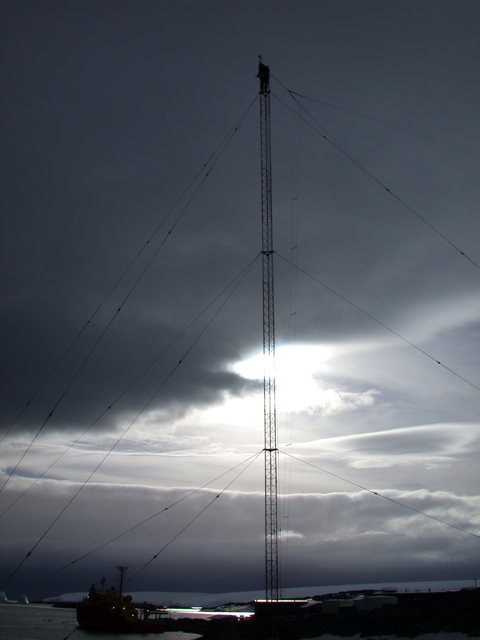

Height of their professionAntenna riggers work above the snow and ice of AntarcticaPosted October 9, 2007

Michiel Lofton tells a story familiar to many who work outdoors in Antarctica during the busy summer field season. The day was cold, of course. The wind was blowing, of course. Only a slit showed between his fleece hat and neck gaiter, like some polar ninja. Soon ice started to form, creating a frosty covering so thick that he couldn’t see — his very eyelashes glued to the icicles. The difference in this story? Lofton was probably about 90 feet in the air, working on a steel tower standing on a foundation made of ice, held aloft by guy-wires anchored into the snow. He pulled out a pair of pliers, carefully broke the ice, and returned to work. “You have to be creative,” says Lofton, referring to not just how one deals with Antarctica’s bitter weather but also on how to approach the job of antenna rigger. The riggers make up a small corps of specialized workers whose domain is above the ice and snow — maybe just 10 feet up on a radio tower or a more dizzying 40 feet on a wind generator. “That’s where it gets fun for us because we’re never working on concrete,” says Andrew Asher, a tall, solidly built antenna rigger whose stateside construction experience includes ironwork. “There’s no heavy equipment,” adds Asher, who, along with Lofton and Jim Boaz, was in Punta Arenas, Chile, in February before heading down to Palmer Station “The crane is the biggest thing we could use,” Asher notes. Of course, it’s not possible to get a crane at the top of the McMurdo Dry Valleys “We never have the time acclimate for Erebus,” Lofton says. “You get up there and start wheezing and lugging heavy equipment around.” At its most basic, the job of Antarctic antenna rigger often involves erecting new towers at far-flung corners of the continent, usually for communications or for wind generators at field camps, as the U.S. Antarctic Program Sounds simple enough until you consider that the riggers are probably standing on blowing snow and ice, the location is probably less than hospitable, and the helicopter that just dropped them off will be back at the end of the day. No time to stand around and shoot pictures. Over the years, the riggers have developed their own system of ropes, pulleys and strategies for erecting the towers — a blend of commercial standards and techniques culled from mountaineering and wilderness rescue training, according to Asher. “We’re on snow. We’re on ice. That dictates our anchor system,” he explains. The rope system also helps them do their job “more effectively and safely,” adds Lofton, a slight man who often hauls 40 pounds or more of equipment and clothing up and down towers all day long. “It gets heavy real quick,” he says, noting that it takes experience to balance equipment needs and cold weather gear. “Generally when we climb up we have to wear just enough clothes to be up there for a while in one spot, but not too much because we have to be mobile. Big Red is out of the question,” he says, referring to the iconic heavy parkas of the USAP. Asher says most of the work at Palmer Station will be maintenance of existing equipment, such as restringing the copper strands on the rhombic antenna behind the station. Other scheduled work included installing an anemometer, a device for measuring wind speed, on a tower on Outcast Island, one of the outer islands. At South Pole Station Every day brings new challenges — though the toughest part of the job may not be the cold, the wind or its physicality. “It’s really heartbreaking when something falls that you need,” Lofton says. |

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsNational Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |