Winter work orderSouth Pole research associates head into the cold in support of sciencePosted July 15, 2011

Most of the big science at the South Pole Station Those instruments study cosmic background radiation outside of the visible spectrum, or search for extraterrestrial neutrinos that reveal themselves in the darkness of the deep ice sheet below us, and are not affected by whether the sun is shining over our heads or not. Their reason for being at the South Pole is to take advantage of the extreme dry and stable atmosphere here — the driest in the world, in fact — or to take advantage of the massive amount of ice that can be used as a naturally occurring particle detector. Other research at the South Pole, on the other hand, takes advantage of the darkness of the winter sky, and our proximity to one of the geomagnetic poles of the earth. That research studies the auroras, the ionosphere, the mesosphere, and the geomagnetic storms in what we generally call space weather. Space weather refers to the disturbances in the balance of charges in the ionosphere, as solar flares, also known as coronal mass ejections, approach the Earth. The ionosphere is a layer of the atmosphere about 60 miles above the surface of the Earth, which is rich in charged particles. It also allows us to do radio communication over long distances by reflecting the radio waves back to earth.

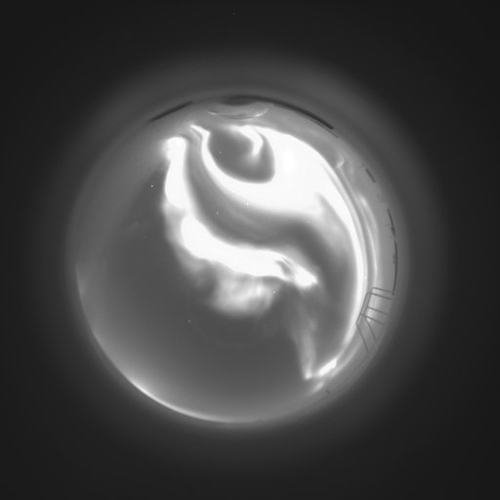

Photo Credit: Sue O’Reilly

An aurora as seen by an all-sky camera. This particular camera is tuned to a specific wavelength corresponding to one of the emission lines of the oxygen-hydrogen bond in the mesosphere.

Photo Credit: Daniel Luong-Van/Antarctic Photo Library

Center of the Milky Way Galaxy with an aurora in the foreground at the South Pole.

When a sun flare interacts with the ionosphere, radio wave communications are disrupted, air traffic needs to be rerouted, satellite communications are in jeopardy, GPS readings lose accuracy — and spectacular auroras show up around the polar regions. One of the objectives of the space weather research at the South Pole is to measure the density of charged particles in the ionosphere and the variations in the magnetic field of the Earth, and to correlate those observations to the intensity and the movement of auroras. The research performed at the South Pole is further correlated to similar observations performed in regions closer to the North Pole, which we call our conjugate region, and to direct observations of solar flares. Three research associates, Sue O’Reilly, Nicholas Strehl, and I are at the South Pole this winter to operate the space weather instruments. We make sure that the computers that acquire the data and transfer them to scientists around the world operate properly, ensuring that they store and back up some of the data that cannot be transmitted over the Internet connection. We also perform periodic calibrations of the instruments, and we ensure that the cameras pointed at the sky remain free of snow and frost to provide the clearest possible images of even the faintest lights. For that reason, every day of the year, we don our extreme cold weather (ECW) gear and climb on the roof to inspect the cameras and clear them of any snow accumulation — whether it is minus 90 degrees Fahrenheit or whether it is blowing a 20-knot wind. Sue and I are responsible for six of them on the roof of the main station, while Nick monitors two of them on the roof of the Martin A. Pomerantz Observatory (MAPO). Our cameras are very specialized and complex scientific pieces of equipment. We call them all-sky cameras because they look at the entire sky with a field of view of 180 degrees. Each looks at a particular emission wavelength from the sky, investigating a different celestial phenomenon. They use filters to select specific frequencies of the visible spectrum and use thermoelectric coolers to reduce the noise in their CCD detectors. Some of them even use image intensifiers, which make them so sensitive that even the light from the moon can blind them, so we need to turn them off when the moon reaches a certain elevation in the sky. The cameras look at the sky through thick hemispherical glass domes located over corresponding holes on the roof of the building. These domes, each a couple of feet in diameter, protect the cameras, their electronics, and their mechanical components from the elements. Unfortunately, the inside of the domes can easily be coated by a layer of frost, as the warm air from the laboratory reaches the cold surface of the domes. Therefore, working closely with the scientists responsible for the instruments, we develop special skills and strategies to identify and mitigate the early formation of frost. These involve the use of dehumidifiers, heaters, fans and special high-purity gases strategically circulated around the domes. Attempts are being made to automate the process of snow removal and frost prevention, so that eventually these all-sky cameras could be deployed to remote stations on the continent. Nick is responsible for monitoring the performance of two of these experimental cameras on the roof of the MAPO building. Being at the South Pole in the winter and experiencing the polar night sky, along with its auroras and stars, while contributing to the progress of science, is a rare privilege that we welcome despite the challenges of the polar winter. |

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsNational Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |