|

Island timeLatest glacier calving near Palmer Station reveals another separate land areaPosted March 28, 2014

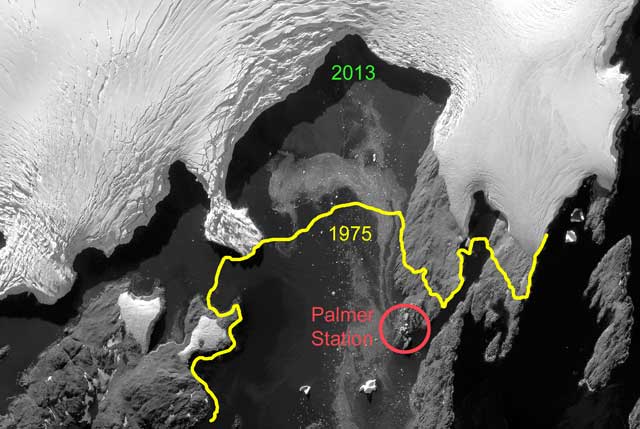

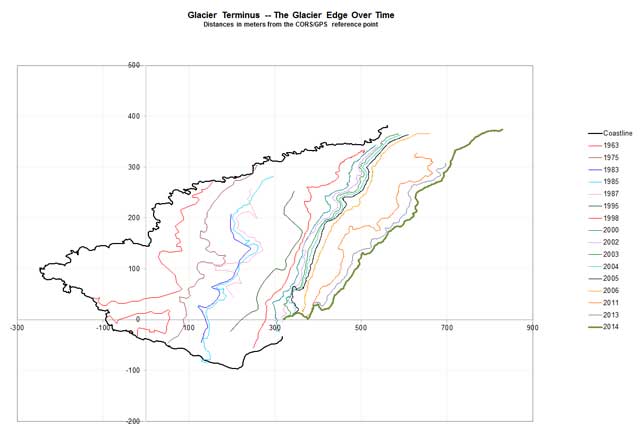

The ongoing retreat of a glacier off the Antarctic Peninsula has unveiled a new island. Personnel at Palmer Station It’s the latest sign of climate change in one of the most rapidly warming regions on the planet, where the average temperature has increased between 2 and 3 degrees Celsius in the last 60 years. In 2005, researchers with the British Antarctic Survey The Marr Ice Piedmont – ice covering a coastal strip of low-lying land backed by mountains – glacier has retreated more than 300 meters since 1975, according to Glenn Grant, research associate at Palmer Station. The glacier was once a short walk behind Palmer Station. “Now it’s a fair distance across some rough terrain,” noted Grant, who first started working at Palmer Station in 1995. “We’ve all noticed that it has been retreating over the years.” The glacier terminus before 1998 was determined from aerial photos. Since then, Grant and other research associates at the station have surveyed the edge of the ice using differential GPS, which provides very accurate, high-resolution measurements. They have created a detailed map showing the retreat history based on the “original” location of the glacier terminus in 1963 from a U.S. Navy aerial photo. The March 14 calving event isn’t the first to reveal an island once thought to be part of Anvers Island, a mountainous isle about 60 kilometers long. “There's been quite a few islands exposed in recent years,” Grant said. “Most are small, little more than rocky shoals, but there have been a few larger ones.” For instance, a nearby spot of land dubbed Dead Seal Point was exposed by the retreating glacier about 15 years ago, according to Grant. Since that time, a small chain of islands has been revealed, and Dead Seal Point has officially become Dead Seal Island. In 2004, during another calving of the Marr Ice Piedmont, it was discovered that Norsel Point, formerly home to the original Palmer Station, was on an island separate from Anvers Island. The “new” island was named Amsler Island Chuck Amsler is currently the program director of the Antarctic Sciences Organisms and Ecosystems

Photo Credit: Glenn Grant

A closer look at the collapse of the ice bridge that connected the small island with the rest of the glacier.

“It was pretty clear last season … that was going to be a new island very soon,” Amsler said. “A lot of us have been convinced for several years that it was going to be one.” There is even speculation that Palmer Station itself may not actually sit on Anvers Island, but on yet a different island attached to Anvers by ice. The retreat of the ice has also revealed a different mystery – bright blue rocks are emerging from under the glacier as it melts back. Grant said his investigation into what the rocks may be hasn’t yielded any conclusions yet. “The blue color appears to be a salt or precipitate that is collecting on some rocks,” he explained. “It also seems to be slightly water soluble, because it’s washed off of rocks after they have been exposed to the weather for a while – we’re finding it only on the most recently exposed rocks.”

Photo Credit: Kelly Jacques/Antarctic Photo Library

The Marr Ice Piedmont as seen from Palmer Station.

Grant may soon have more time to work on the different issues of glacier retreat. Next fall, he’ll enroll in a PhD program at the University of Colorado in Boulder “One of the main topics I'd like to study is glacial retreat along the Antarctic Peninsula,” he said, “so I have a keen interest in our glacier data.” Amsler, who has worked Palmer Station since 1985, also has a keen interest in the changes under way in the region. “There was so much more glacier and so much less of that part of [Arthur] Harbor [in 1985],” he recalled. “It is the same way behind the station, because the glacier really was almost right behind Palmer then, and it had a huge area on top that was safe for recreation. The area that one can safely access on it now is a small fraction of what people used to be able to enjoy. “As impressive – and scary – as the changes in the glacier at Palmer are, they are really just one of many illustrations of the changes going on along the Peninsula that are so quickly altering the biotic communities there,” Amsler added. “It is sad to be witnessing this in just part of one’s professional lifetime.” |

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsNational Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |