|

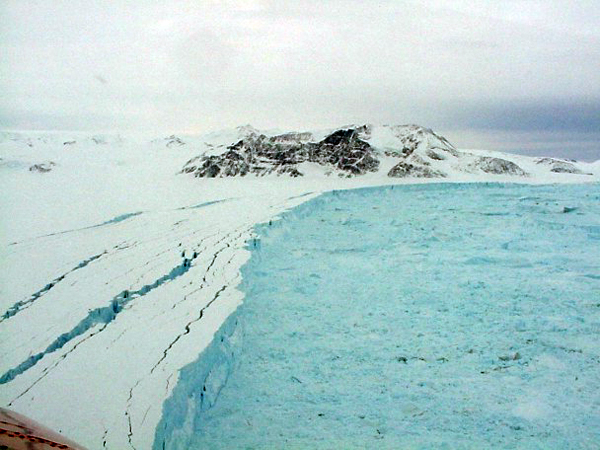

Project along peninsula will take ice core to bedrockThe peninsula, most polar scientists will tell you, is warming more rapidly than just about anywhere else on the planet. The total increase in mean annual air temperatures is about 2.8 degrees in the last 50 years, while mean winter temperatures have risen even more — 6.5 degrees Celsius during that same time. The Larsen Ice Shelf is a long ice shelf in the northwest tip of the Antarctic Peninsula on the Weddell Sea side. The Larsen is actually — more accurately, was — a series of three shelves. The Larsen A disintegrated in 1995 and the Larsen B fell away in 2002 in spectacular fashion. The Larsen C, the largest of the trio, is still holding on. “Since then, the glaciers that were buttressed by this shelf are now discharging ice four, five, six, seven, eight times faster to the ocean,” Mosley-Thompson explained. “The concern is that they contribute to sea level rise.” In fact, ice loss in Antarctica increased by 75 percent in the last 10 years, as glaciers sped up, and is now nearly as great as that observed in Greenland, according to a study by NASA and university scientists released earlier this year. LARISSA seeks to get a “big picture” view of the Larsen area using a variety of tools, including GPS to learn more about the ice dynamics, and drilling ice cores to study the climate history. Mosley-Thompson said the cryosphere team hopes to drill at least one ice core down to bedrock, about 500 meters. Sediment cores previously drilled in the area by Domack and his colleagues show that the Larsen B had been in place for at least 10,000 years, according to Mosley-Thompson. “If that’s true, then it’s very likely that ice shelf was in place for a much longer time.” That means there’s a possibility of drilling into glacial stage ice, before the beginning of the Holocene, which would represent one of the oldest ice core records from the Antarctica Peninsula, according to Mosley-Thompson. Photo Credit: Wikipedia Commons

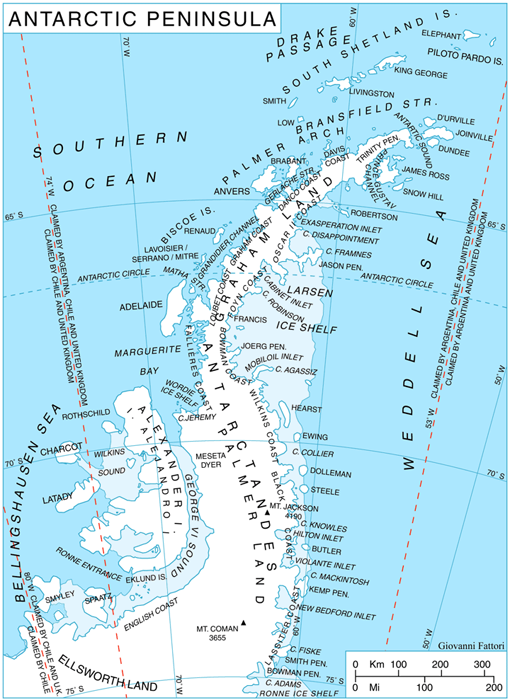

Map of Antarctic Peninsula.

“Because ice layers thin rapidly near the glacier bed and the ice where we plan to drill is about 500 meters thick, the team will be thrilled to extract a history reaching back about 25,000 years — although a longer record is always possible,” she said. In comparison, ice cores in East Antarctica, where the ice is nearly 4 kilometers thick, the longest record goes back much further in time, about 800,000 years. The snow accumulation rate should be high enough that the team will get what’s called annual resolution in the upper sections of the core, which allows them to tease out details about climate year to year. Think of it a bit like a digital camera: A high-resolution image provides much greater detail in each pixel, allowing you to enlarge the picture. A low-resolution shot loses detail and begins to blur as the photo expands in size. The data the researchers collect will add to our understanding of climate change, particularly in a rapidly changing area, with the Larsen B the poster child of abrupt environmental collapse. The Wilkins Ice Shelf, a much younger ice shelf on the other side of the Antarctic Peninsula, began to break up late in the austral summer, and European scientists reported in June that it’s continuing to collapse, despite the onset of winter. (See related story: Winter no relief.) Many scientists expect ice in West Antarctica and Greenland to continue to recede significantly in the next century if temperatures continue to rise, with more collapses like that of the Larsen and Wilkins ice shelves. Mosley-Thompson said she often lectures about the changes under way on the planet, connecting ice core science with how a warming world transforms both human systems and ecosystems, resulting in more extreme weather events, such as alternating droughts and floods, which destroys arable land and reduces water supplies. “The impacts will be variable — there will be winners and losers — probably more losers than winners though. Some areas will likely experience high prices for food and energy while other areas may experience widespread devastation, producing a generation of environmental refugees,” she said. “All of that is tied to climate change.” NSF-funded research in this story: Ellen Mosley-Thompson, The Ohio State University. |

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsNational Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |