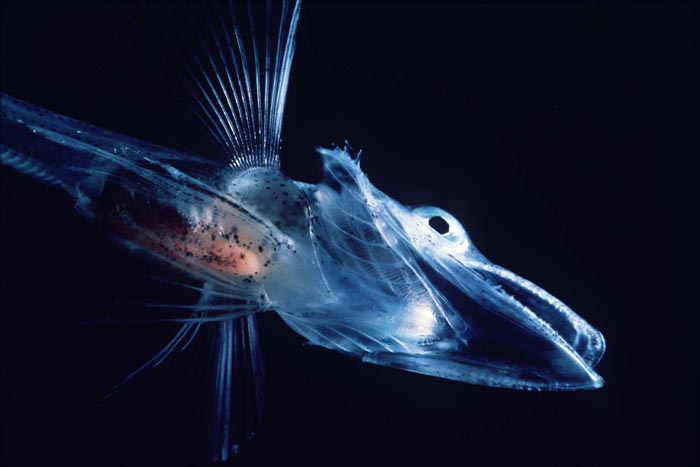

More than cold bloodedA lightweight skeleton isn’t the only quirk of evolution that makes icefish appealing for biomedical purposes. Detrich’s lab has previously done work on the blood of these fish. “They’re the only group of vertebrates in the world — 16 species of icefish out of 50,000 vertebrate species worldwide — that don’t make hemoglobin, the component of red blood cells which transports oxygen to cells. Their blood is transparent.” More Information

Find out more about icefish from a 2004 expedition: ICE FISH Cruise

Detrich said they likely evolved this trait because they live in the cold, stormy waters around Antarctica; the very cold Southern Ocean dissolves much more oxygen than tropical waters. The icefish obtain oxygen in physical solution through their gills and directly through their skin. Detrich said it is possible to compare red and white blood cell fish, “subtract the genomes, if you will, and what should fall out are the genes in the red blooded fish that are no longer being expressed by the white blooded fish.” The process is called gene subtraction. “In fact, we have discovered new genes previously unknown to be involved in making red blood cells by this process,” he said. “The ultimate hope would be that these could provide new avenues for therapies for anemia and things of that sort.” A fish at its limitBut the icefish have made evolutionary sacrifices along the way. Their more temperate cousins can exist in ocean water of widely varying temperatures. Not so with the Notothenoids. “The icefish could not live in tropical waters because the warm waters contain much less oxygen and they’re not as well mixed,” Detrich explained. “For many reasons, these fish would not survive in warmer temperatures. They don’t have a heat shock response, for example.” While Detrich’s research does not look directly into how climate change may affect icefish, a rise in ocean temperature does concern him, particularly in the peninsula area, which is warming more rapidly than other regions on the planet. “I can say anecdotally over the course of about 25 years of visiting Palmer Station I’ve been watching the glacier retreat and so on. The winter is no longer as cold as it used to be. Some very profound changes are going on,” he said. “My concern is — and I think this is starting to motivate the work of a lot of fish biologists in the Antarctic — most of the species there are only going to be able to tolerate relatively small temperature changes in the ocean. If we see really dramatic changes, many of the fish would probably go extinct, not to mention many of the invertebrates that live at minus 1.8 centigrade. “It is a concern.” NSF-funded research in this story: Bill Detrich, Northeastern University, Award No. 0635470 |

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsNational Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |