Seeing the forest for the treesPaleobotanists discover new fossil flora in AntarcticaPosted February 12, 2015

A series of hills that form a wishbone shape at the extreme northwest corner of the region known as the McMurdo Dry Valleys appear lifeless today. Splashes of dirty white snowfields overlay parts of the muted camouflaged landscape of the Allan Hills, composed of patches of dark brown volcanic rock and beige slabs of sandstone. Erik Gulbranson trudges up a steep ridge overlooking his field camp of mountain tents and pyramid-shaped Scott tents abutting one such snowfield used for fresh water. The one small speck of civilization disappears from view as the scientist drops down the opposite, shallower slope and across a broad saddle. A brief hike nearly to the top of a shorter ridge ends at the quarry, where picks and hammers have chopped out a ledge of sorts in the slate-grey hillside.

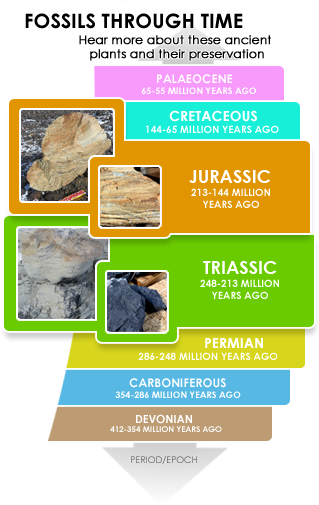

Click the photos for additional audio information on Jurassic and Triassic-era fossils found in Antarctica.

Voice of Erik Gulbranson | Transcript

Voice of Carla Harper | Transcript

Voice of Erik Gulbranson | Transcript

Voice of Erik Gulbranson | Transcript Sometime about 220 million years ago, a meandering stream flowed here – and plants grew along its banks. An unknown event caused sediment to flood the area rapidly, which helped preserve the flora. Gulbranson splits open a grey slab of siltstone in the quarry to reveal amazingly well-preserved Triassic plant fossils, as if the leaves and stems had been freshly pressed into the rock only yesterday. “It’s a mixture of plants that don’t exist anymore,” said Gulbranson, a visiting professor at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, “but we have some plants in these fossil ecosystems that we might know today, like Ginkgo.” On the one end are fossils from an extinct genus of fork-leaved seed ferns called Dicroidium that dominated during the Triassic, a geologic period that lasted from about 252 to 200 million years ago. Other plants frozen in time on this remote hillside include species in the extant cycad family, which today favor subtropical and tropical climates. Even better are the fossilized specimens no one can yet identify. “They’re brand new to Antarctica,” said Gulbranson, who is co-principal investigator on a project investigating the evolution of ancient plants in Antarctica and the high-latitude environments in which they grew. Also new to Antarctica: A Triassic-age fossil forest of 37 tree stumps, located less than a couple of kilometers almost directly south from the quarry and discovered about a week after Gulbranson and a team of paleontology experts in plants, fungi and other disciplines arrived at Allan Hills by helicopter and Twin Otter.

Photo Courtesy: Gulbranson and Serbet

One of 37 fossil trees found in Allan Hills. It is the second largest fossil forest ever found in Antarctica.

It is only the second fossil forest from the Triassic ever found in Antarctica. It’s about a third the size of a site in Gordon Valley near the Beardmore Glacier in the Transantarctic Mountains. The Gordon Valley fossil forest, discovered in 2003, contains 99 preserved seed-fern tree trunks. The trees are estimated to have grown about 20 meters in height along what were likely the banks of an ancient river system. The newly discovered Allan Hills fossil forest, at the base of the 1,800-meter-high Roscolyn Tor, represents the second largest fossil forest in Antarctica, according to Gulbranson. About a dozen fossil forests have been found from an even earlier time period called the Permian, which extends roughly between 298 and 252 million years ago. “It’s an important find,” said Gulbranson, whose expertise as a sedimentologist and geochemist allows him to reconstruct the environment that existed when these trees, shrubs and forests flourished by using various techniques, including grinding down small samples of the fossil growth rings to see variations in how the ancient flora once grew. Even without the high-tech lab analyses, Gulbranson can make some interpretations by investigating the environmental setting. “We know this fossil forest was an early succession forest, so something that emerged after some kind of disturbance event – a fire or insect predation or some kind of parasite,” Gulbranson explained. “We’ve got these really weird forests here – these really weird climates – and we want to know how they developed, how they got here,” he added. “That’s the bigger picture: How did polar forests develop and what impact does that have on climate?” |

"News about the USAP, the Ice, and the People"

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsNational Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |