|

House callLarsen C project to monitor ice shelf's health before its eventual collapsePosted October 3, 2008

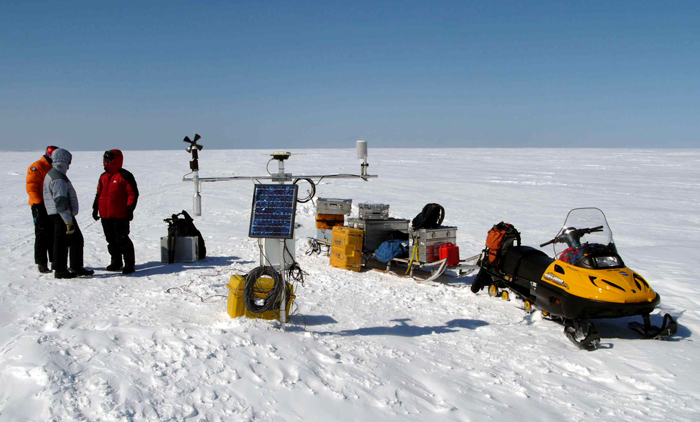

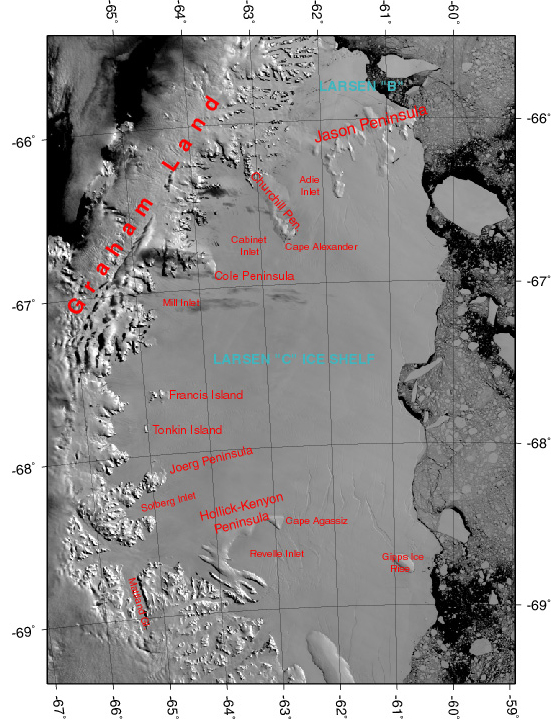

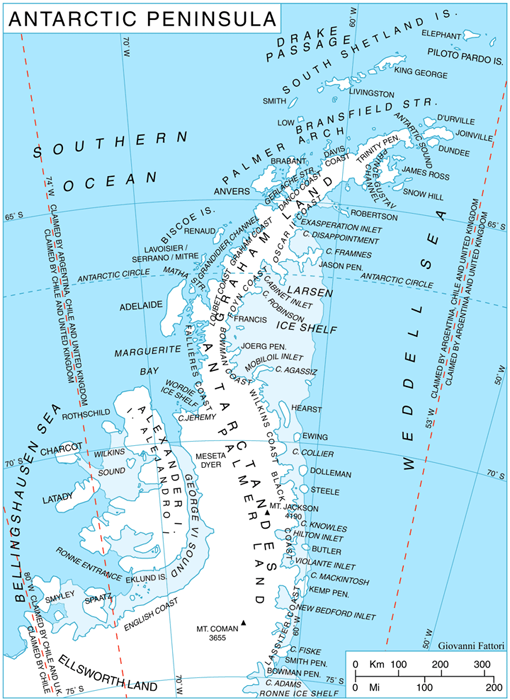

Konrad Steffen is one of the world’s leading experts on climate change in Greenland, having traveled to the ice-covered island every year since 1990. He oversees a network of 22 weather stations that collect data about the ice sheet, and returns with his graduate students each year to the same field camp north of the Arctic Circle to study how the ice sheet and its glaciers are responding to a warming climate. Greenland is the poster child for global warming, the canary in the coalmine, and every other cliché used to describe the phenomenal amount of ice loss under way — a discharge causing sea level to rise steadily, millimeter by millimeter, like grains of sand passing through an hourglass. Far away, in another hemisphere, the West Antarctic Ice Sheet and its glaciers are pouring ice into the ocean just as quickly. And at the northern tip of the Antarctic Peninsula, which juts away from the continent like a rhinoceros horn, temperatures are rising faster than just about anywhere on the planet. The disintegration of large ice shelves, formerly thought a once-in-a-lifetime occurrence, has happened twice already in this decade. This is where Steffen and NASA “Our focus is to measure the Larsen C from the glaciological viewpoint and climatological viewpoint … To find out what is happening in a warming climate,” explained Steffen during an interview in his office at the Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences (CIRES) The Larsen Ice Shelf was a series of three ice shelves with distinct embayments in the northwest Weddell Sea. The Larsen A sloughed away in 1995, and the Larsen B followed in a spectacularly rapid fashion in February 2002, though a relatively small chunk remains. Farther south and larger than the states of New Hampshire and Vermont combined, the Larsen C may disintegrate within the next decade. Like physicians visiting a terminally ill patient, Steffen and Rignot want to monitor the ice shelf before it disappears — an opportunity that has eluded scientists in the past. Earlier this year, the Wilkins Ice Shelf on the west side of the peninsula began its fitful breakup, a process that continued through the winter. [See related story: Last thread] “We want to study the state of the health of the [Larsen] ice shelf and predict when it might collapse,” said Rignot by phone from his office at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) Ice shelves themselves don’t contribute to sea level rise, but their disappearance allows the glaciers that feed them to flow freely and more quickly into the ocean. Understanding the processes that contribute to destroying these floating blocks of ice, which can be several hundred meters thick, will help the scientists develop better computer models for ultimately predicting how high the seas may rise in the future. “The modeling is only as good as we understand the process. Currently, we know very little about the process of ice shelf disintegration,” Steffen explained. What the scientists do know from satellite data and some past studies is that the ice shelf is definitely warming and changing. Rignot said Larsen C is thinning at the north but possibly thickening to the south. The region receives some of the heaviest precipitation on the entire continent, most of which is a polar desert. Satellites have observed melting on the shelf surface, Steffen noted. “We can see these melt waves going across the entire Larsen C that did not happen earlier on, like 10 years ago,” he said. |

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsNational Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |