Race to the endAMNH showcases famous competition between Scott and AmundsenPosted November 5, 2010

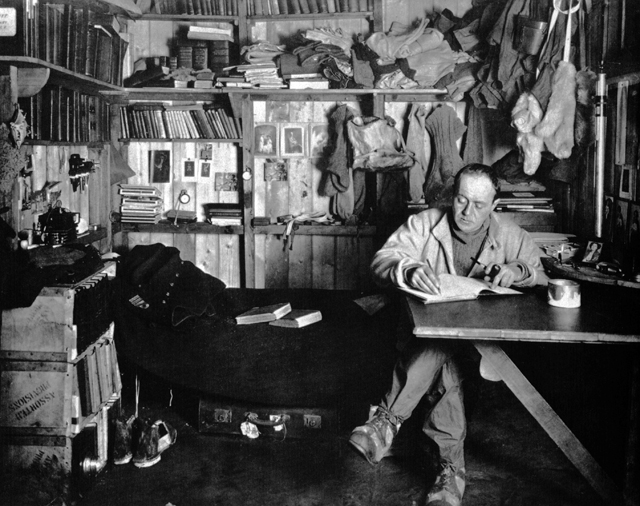

It was one of the great rivalries of the 20th century — a sort of heavyweight matchup of the day’s great polar explorers. In one corner you had Roald Amundsen, the Norwegian adventurer who led the first expedition to successfully traverse Canada’s Northwest Passage between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. In the other corner, Capt. Robert F. Scott, a British Royal Navy officer whose early exploits in the Antarctic made him a national hero. In 1910, Amundsen threw down the gauntlet to Scott, sending his rival a telegram out of the blue that read simply: “Beg to inform you Fram proceeding to Antarctic — Amundsen.” The race to be the first at the geographic South Pole, the last great prize in the Heroic Age of Exploration, was on. The American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) Ross MacPhee “It has all the elements: Competition between two very capable, yet very different, leaders. It has the element of a place still untrodden by human feet,” MacPhee said. An expert in paleomammology — a fossil hunter interested in the evolution and distribution of mammals through time — MacPhee has a special interest in polar history even though he’s not a card-carrying historian. “I’ve always been interested in the history of exploration, even when I was working in the tropics … because you can’t help but be fascinated and impressed by these guys, especially in the 19th century when geographical discovery was a significant component of scientific inquiry,” MacPhee explained. The paleontologist himself has led three expeditions to the Antarctic Peninsula since 2007 with funding from the National Science Foundation He can also empathize with explorers like Scott and Amundsen. His attempts to prospect for fossils so far have largely been stymied by freak storms and plentiful sea ice in the region. He and his team will make a fourth try for the islands off the western tip of the peninsula in February 2011. Still, MacPhee shrugs off comparisons between expeditions of today and yesteryear, when today’s scientist-explorers stream through the Southern Ocean on modern icebreakers versus the leaky, crowded wooden ships of their forbearers. “We have it so good by contrast. You can’t help but be impressed by the things those men accomplished,” he said. The AMNH exhibit is intended to do just that — impress upon a new generation the sort of technological and environmental challenges the Norwegian and British teams faced at the turn of the 20th century. Combining artifacts and photographs from the expeditions, highly detailed and artistic dioramas, and even life-size recreations of the living conditions, the exhibit offers the public a unique window into the history of the age. A short introductory video sets the stage for the race — revealing nothing of how it all ends — before sending the visitor through a series of displays that build the narrative while providing context for the story. For example, visitors encounter a partial reproduction of Scott’s expedition hut, from where he launched his bid for the Pole, based on photographs by Herbert Ponting. Some 25 men lived together in cramped conditions. The realism of the display is a bit unnerving — rough-looking socks hang from bed railings, as if the men had just stepped away for a moment. MacPhee said a survey conducted by the museum before the exhibit was created found many Americans weren’t familiar with the Amundsen and Scott tale — a challenge and opportunity. “If most people don’t know the story, then they don’t know how it ends,” he said. “The way we presented it was as though it really were a race. You don’t know the outcome until three quarters of the way through.” Spoiler alert: “People are shocked that Amundsen wins and Scott dies,” MacPhee added. Amundsen attained the Pole on Dec. 14, 1911. Scott and his crew arrived about five weeks later, on Jan. 17, 1912, and were completely demoralized by their second-place finish.1 2 Next |

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsNational Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |