Fresh airNOAA observatory takes in the atmosphere at the South PolePosted August 19, 2011

The phrase “a breath of fresh air” takes on a whole new meaning at the South Pole in Antarctica. The U.S. Antarctic Program’s research station But the South Pole Station’s Atmospheric Research Observatory (ARO) “We’re trying to capture the cleanest air possible in order to get levels of gases, aerosols in the atmosphere that aren’t influenced by people,” explained National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) “All of that data is put into our climatology models and distributed to the public and for other people to use as well,” she added. “That’s our basic mission here.” ARO is one of the six atmospheric baseline observatories for NOAA’s Earth System Research Laboratory’s Global Monitoring Division The data from those early measurements, when combined with the more famous observations made from Hawaii’s Mauna Loa Observatory

Photo Credit: Scripps

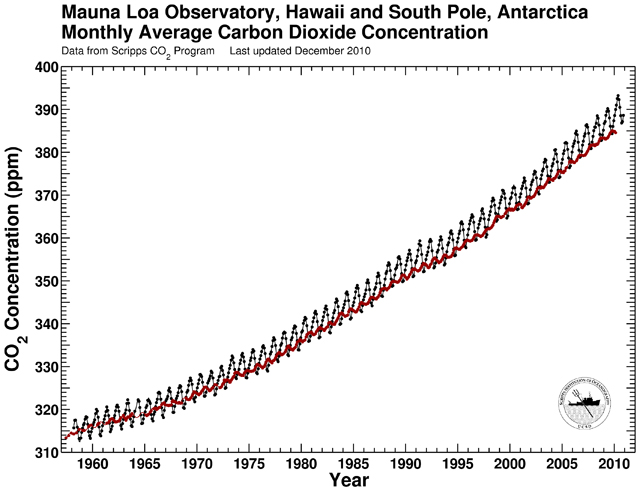

The Keeling Curve shows the upward trend of carbon dioxide concentrations in the atmosphere from measurements made at the South Pole (red) and Hawaii (black) since the 1950s.

Glass flasks of South Pole air are still sent to Scripps for the ongoing monitoring program. But that’s not all that goes on ARO, which was built by the National Science Foundation (NSF) The observatory is also a key site in ozone hole depletion research, a science that began in the 1980s after the hole was discovered by British researchers in Antarctica. NSF and NOAA scientists later led the research that found the main culprit was the emission of manmade chlorofluorocarbons in the atmosphere. Schultz and NOAA technician Johan Booth operate several instruments year-round to monitor ozone. Weekly balloon launches — more during the Antarctic spring and early summer when the hole appears and gains strength with the formation of the polar vortex — transmit data about ozone levels in the stratosphere. In addition, ground-based instruments also provide information about ozone concentrations. One called the Dobson ozone spectrophotometer

Photo Credit: Jeremy Johnson/Antarctic Photo Library

A black and white photo of ARO during the winter. The moon-like sphere in the sky is actually a reflection on the camera lens. The beam of light shooting up from the building is a type of laser that monitors atmospheric ozone, temperature, aerosols, water vapor, and polar stratospheric clouds.

“This is a really cool instrument, because it was created in the 1920s by Dr. Gordon Dobson,” Schultz explained. “He was originally looking to see if he could use ozone to look at circulation in the atmosphere but instead it ended up being useful to look at the concentration of ozone. These instruments really haven’t changed since then.” In fact, the Dobson spectrophotometers played a pivotal role in convincing researchers that the ozone layer, which helps block harmful ultraviolet radiation from reaching the Earth, was being depleted. Thanks largely to a global agreement to phase out CFCs and other harmful organic compounds, called the Montreal Protocol, the ozone layer is expected to recover by century’s end. “We’re really doing important research,” said Schultz, one of about 300 people that make up the NOAA Commissioned Corps Officers, who operate one of NOAA’s 19 ships or 12 aircrafts. Her previous assignment was conducting hydrographic studies in Alaska. Running ARO is a bit like working on a research vessel, Schultz said, albeit a roomier one in a frozen and still ocean. “It’s a pretty coveted position,” she said of the post at ARO. “Not many people get to go to the South Pole, and to come down for NOAA is a pretty hard thing to achieve. … It’s been a dream of mine for a while to do this. I’m so amazed to be down here. I feel very fortunate to have made it.”

|

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsNational Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |