|

Big haulPaleontologists return from Antarctic expedition with about 200 fossilsPosted September 16, 2011

Ross MacPhee Third time’s a charm? Try the fourth. Related Articles

“We did quite well,” MacPhee said of his most recent expedition to a series of islands off the Antarctic Peninsula where he and fellow paleontologists recovered a couple hundred fossils of marine reptiles, birds, fishes, plants and even a few tantalizing fragments from what appears to be two different dinosaurs. But the big prize — Cretaceous mammalian fossils that could bolster theories about vertebrate dispersal through the southern hemisphere — still eluded him. “All the biogeographical indications are that mammals had to have been there,” said MacPhee, a curator in the mammalogy department at the American Museum of Natural History Before wandering to its present position and entering into a deep freeze nearly 40 million years ago, Antarctica was sandwiched between South America and Australia as part of the former supercontinent Gondwana. Even as the continent separated, land bridges likely persisted between the southern continents for millions of years, offering plenty of opportunity for animals to traverse across the bottom of the world. MacPhee is particularly interested in the history of Australian marsupials, believing that their ancestors emerged in South America and traveled across Antarctica to Australia sometime in the neighborhood of 80 million years ago. He is even of the mind that it’s just possible that some critters might have first sprung up in Antarctica and spread out to the north. “It’s surprising to me that we got no evidence this time because we were able to hit one area called Sandwich Bluff on Vega,” said MacPhee, referring to a rock outcrop on Vega Island that has proven to be a rich treasure trove for Cretaceous-age fossils. Part of the challenge, of course, is that most of Antarctica, even those areas above the Antarctic Circle where the researchers visited, is covered by ice and snow. That limits fossil hunting to the few bald spots of exposed rock. A further complication is the type of rock outcrops that exist on the James Ross Island group located off the tip of the Antarctic Peninsula. The sediments were laid down in a marine setting, meaning fossils from any land vertebrates would have had to get some help getting there, such as being washed into seashore by a river. “[Mammal fossils are] going to be rare because of the type of deposits we have to look in. We’re not looking in conventional terrestrial-style basins,” MacPhee noted. Paleontologist Joe Sertich “Antarctica is thought to be a potential link between South America, Madagascar and India,” explained Sertich, curator of vertebrate paleontology at the Denver Museum of Nature and Science “We’re looking for clues as to how they were connected — if they were,” Sertich said. “Anything would be significant.” The team spent most of its field season at a camp on Vega Island, a small island north of James Ross Island that had previously yielded one of the most significant finds in bird evolution. This discovery offered the first evidence that modern birds existed alongside non-avian dinosaurs at the end of the Cretaceous, a geological period of time that lasted from about 145.5 to 65.5 million years ago. “Antarctica is really a remarkable place to study the origins of modern birds, because the only undoubted members of modern bird groups that have been found from the Age of Dinosaurs come from the James Ross Island Group,” noted Matthew Lamanna “The origin of birds from non-avian dinosaurs is now well-established. If we want to look at the next step in bird evolution … the next step in the chain from something that looks like a Velociraptor to something that looks like a goose, then Antarctica is a great place to go,” added Lamanna, assistant curator of vertebrate paleontology at Carnegie Museum of Natural History Julia Clarke

Photo Credit: Kelley Watson

The 2011 expedition team at camp on Vega Island. From left: Jin Meng, Eric Gorscak, Julia Clarke, Eric Roberts, Matt Lamanna, Ross MacPhee, Joe Sertich and Kelley Watson.

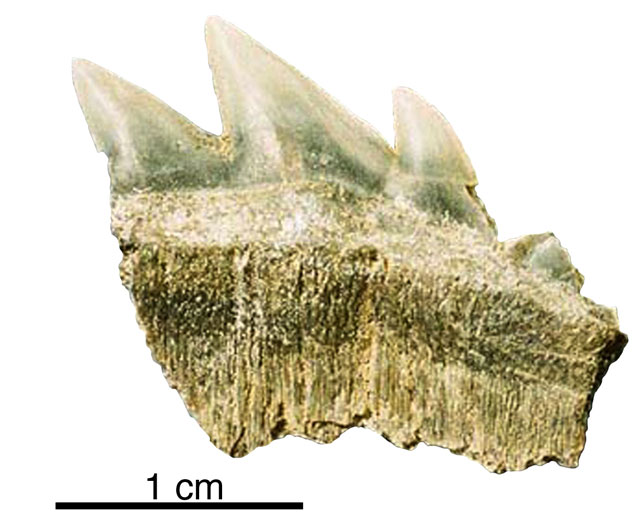

It offered some of the best fossil evidence to date that the modern bird divergence — the spread of some of today’s bird groups — occurred before the mass extinction of non-avian dinosaurs about 65 million years ago. Lamanna said the team recovered about 20 isolated bird bones and one or more partial skeletons in rock concretions. Analysis is just now under way, but he said the group is “encouraged” by what it collected. “Every bird fossil we found appears very advanced, consistent with being a member of a modern group,” he said. A short visit to an area called the Naze on James Ross Island turned up a few non-avian dinosaur fragments from the Late Cretaceous as well. Among the finds was a tooth from a carnivore and a toe bone that may have belonged to a two-legged herbivore. “We’re very optimistic about the Naze. If we get another opportunity to go to Antarctica, we’re going to make the Naze one of our major targets,” Lamanna said. The expedition — MacPhee’s fourth in as many years — was the final one of this grant from the National Science Foundation’s Office of Polar Programs

Photo Credit: Joe Sertich

Southwestern coast of Vega Island, with 2011 expedition camp in the distance.

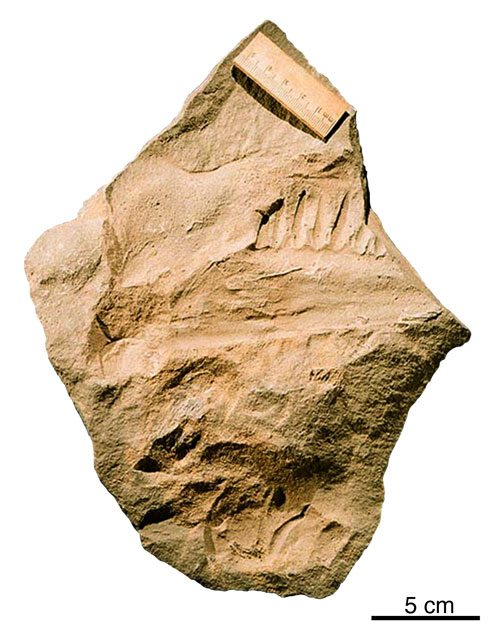

The best specimens found by the expedition came from a group of marine reptiles known as plesiosaurs, including two partial skeletons, one of which may prove to be a new species. Plesiosaurs have been found previously around the island group, including a nearly complete skeleton of a juvenile long-necked (elasmosaurid) plesiosaur, which was discovered in early 2005. [See previous article: Team reveals juvenile plesiosaur fossil in the Dec. 4, 2006 issue of The Antarctic Sun “It’s an indication that at least the waters around Antarctica at that time [during the Late Cretaceous] were just vibrant with all kinds of life,” said MacPhee, who will return to the region once again in January 2012 with Argentine colleagues to continue the search for his elusive marsupials. “It does sound a bit quixotic,” he conceded, but argued that evolutionary theory demands that the evidence should be there. “It would be astounding if after years and years nobody finds anything.” NSF-funded research in this story: Ross MacPhee, American Museum of Natural History, Award No. 0636639

|

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsNational Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |