A good proxyLARISSA project studies ecosystem changes since Larsen A Ice Shelf collapsePosted June 8, 2012

In 2002, the Larsen B Ice Shelf shattered in spectacular fashion, shocking the polar science community with the rapidity of its disintegration. A decade later, a multidisciplinary team of scientists aboard the research vessel Nathaniel B. Palmer Their previous cruise to the Larsen B embayment in 2010 was blocked by sea ice conditions, and the team was eager to try again. “It happened again this year. In a certain way, we weren’t able to accomplish our original goals,” said Maria Vernet In 2010, conditions had forced the ship to retreat completely to the western side of the peninsula, which generally experiences much lighter sea ice. The ship spent the better part of two months working in the western fjords, collecting sediment cores from the seafloor and supporting glaciological work on the peninsula.

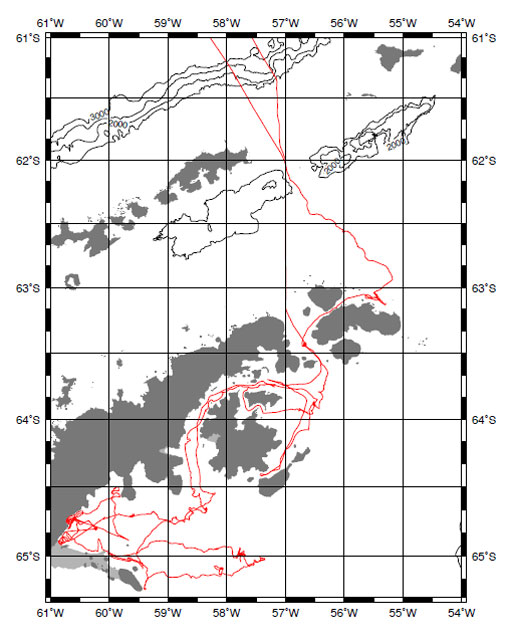

Graphic courtesy: Bruce Huber

Map of the PALMER's cruise around the Antarctic Peninsula and Larsen A region.

While the marine component of LARISSA — one of the major International Polar Year Other researchers managed to install several observatories on the eastern glaciers that once fed the Larsen B Ice Shelf, thanks to the help of the British Antarctic Survey Marine biologists aboard the 2010 cruise made some of their own discoveries, such as spying an invading horde of king crabs on the continental shelf that had been absent from the region for millions of years — another sign that the region is gripped by climate change. Occupying the Larsen AThe 2012 expedition, despite the challenges again presented by the thick sea ice cover, made its own breakthroughs and discoveries. “We were luckier than two years ago, and were able to work in the Larsen A,” said Vernet, a LARISSA co-principal investigator (PI) and a marine biologist from University of California, San Diego’s Scripps Institution of Oceanography The Larsen Ice Shelf is the name early explorers used to describe the nearly continuous ice shelf area in the northwestern Weddell Sea. Glaciologists gave the three distinct embayments different names, as the ice shelves began to change during the last century. The Larsen A, the northernmost, broke apart in 1995 after decades of retreat. The backup plan in 2012 focused on the changes under way in the Larsen A region as substitute for studying the Larsen B embayment. “In the absence of our ability to go to Larsen B, Larsen A was a very good proxy,” Vernet noted. NSF-funded scientists had previously visited the Larsen B region during a series of cruises in the 2000s, led by Eugene Domack Sediment cores recovered during those earlier investigations found evidence that the Larsen B Ice Shelf had been in place for at least ten millennia at the end of the last glacial period, according to Amy Leventer “The Larsen A Ice Shelf, on the other hand, appears to have been more ephemeral, with [a] long period of open water in the region for much of the mid-Holocene,” said Leventer, referring to the current warm period between glacial periods, called an interglacial. “This kind of information is important in terms of understanding the processes that control the formation and loss of ice shelves.” Filtering phytoplanktonThe disappearance of the ice shelf particularly affects the marine biology, from the surface to the seafloor. At the top of the water column are phytoplankton

Photo Credit: Amber Lancaster (PolarTREC 2012), Courtesy of ARCUS

Filtration system for phytoplankton.

The absence of the Larsen A Ice Shelf in recent years means more open water for blooms of phytoplankton, which require sunlight and nutrients to grow. Satellite observations had found big swings of phytoplankton growth in a given year, referred to as interannual variability, according to Vernet. “The remote sensing can detect years of high phytoplankton abundance and production as a function of the sea ice being open,” she said. Sampling from the Palmer from inshore to farther out to the former borders of the ice shelf found marked spatial differences, with higher chlorophyll concentrations away from shore — something also observed from satellites. “We were able to find results beyond the remote sensing [data], and we were able to confirm some of the results we see from remote sensing,” Vernet said.1 2 3 Next |

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsNational Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |