Photo Credit: Mike Lucibella

|

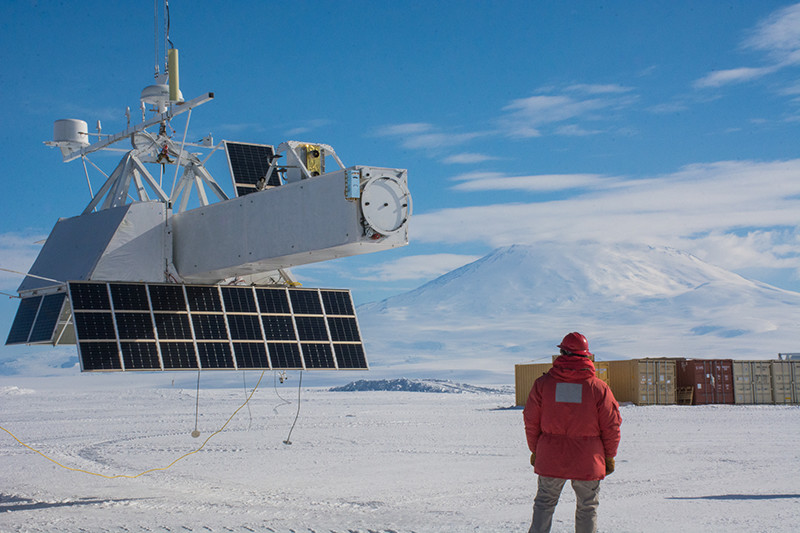

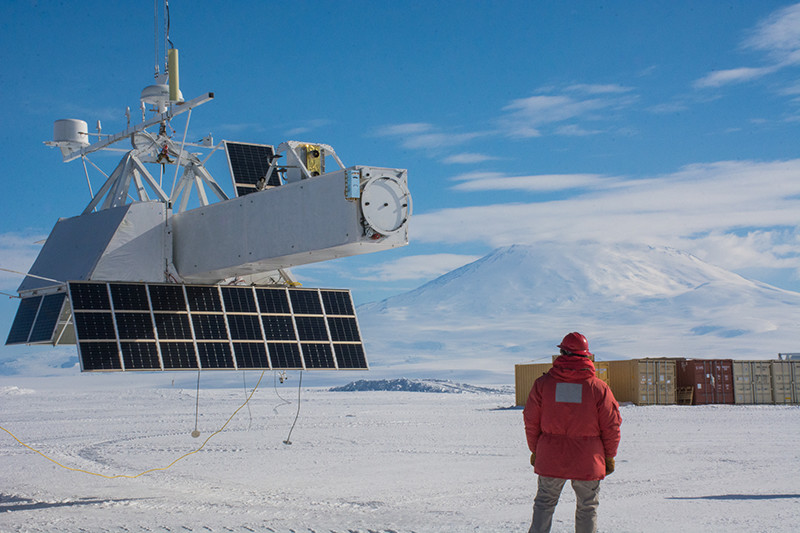

The GRIPS scientific payload hangs suspended over the frozen surface of McMurdo Station’s Long Duration Balloon field as one of launch crew looks on.

|

GRIPS’ Moment Under the Sun

Suspended from a giant balloon, miles above the frozen continent, a telescope watched for eruptions from the sun.

By Michael Lucibella, Antarctic Sun Editor

Posted October 5, 2016

As a giant helium balloon lifted the alabaster solar telescope GRIPS aloft, the excitement on the ground was palpable. The team of researchers, who had spent seven years working on the project, jumped for joy and snapped photos of their experiment in the air for the first time.

Piggybacks

See the scientific hitchhikers that tagged along with GRIPS on its voyage through the stratosphere.

“It’s amazing,” said Albert Shih of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. “I’ve been working on this project for a very long time. It’s the culmination of a lot of work.”

During its nearly two week flight around Antarctica, thousands of feet above the ground, the team trained the telescope at the sun to observe the enormous eruptions of gas and plasma from its surface. The Gamma-Ray Imager/Polarimeter for Solar Flares, or “GRIPS,” is helping researchers unravel some of the persisting mysteries of the sun and the nature of these eruptions.

“We are a telescope that is looking at the sun and we want to understand how particles are accelerated during solar flares,” said Nicole Duncan of the University of California, Berkeley.

Photo Credit: Mike Lucibella

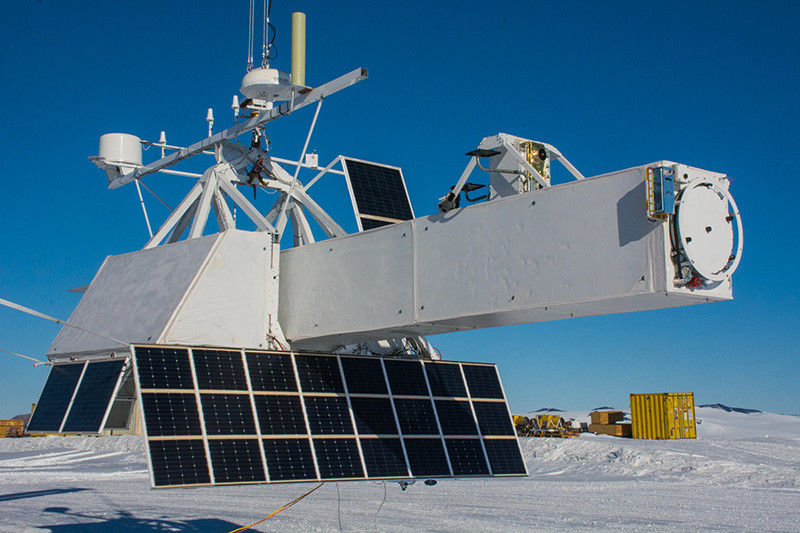

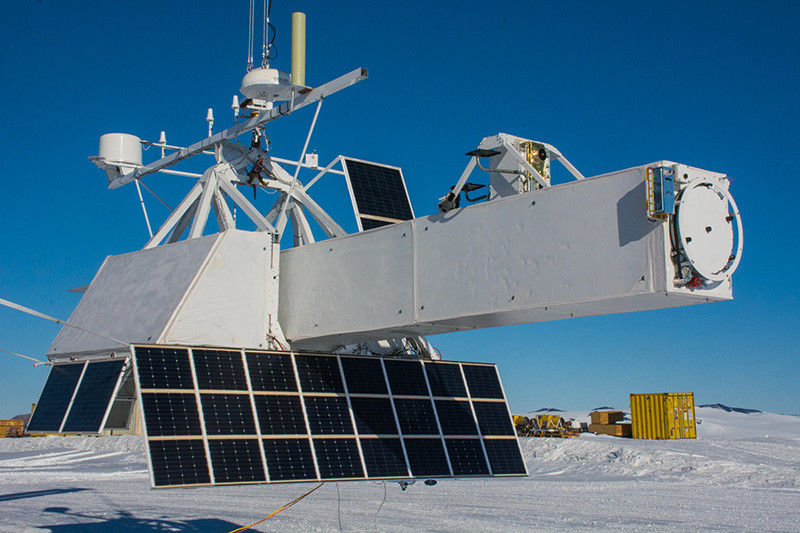

During a hang test before its flight, scientists test the systems of the gamma-ray telescope, GRIPS.

The NASA-funded project was launched by the Columbia Scientific Balloon Facility at McMurdo Station. The National Science Foundation, which manages the U.S. Antarctic Program, is supporting the Antarctic field operations of the project.

Solar flares are large, energetic bursts on the sun that spew tremendous amounts of hot plasma and charged particles out into space. They’re caused by magnetic fields on the sun that get twisted up and release enormous amounts of energy when they “snap” out of their tangled state. But there are still many things that scientists don’t fully understand about the process.

Photo Credit: Mike Lucibella

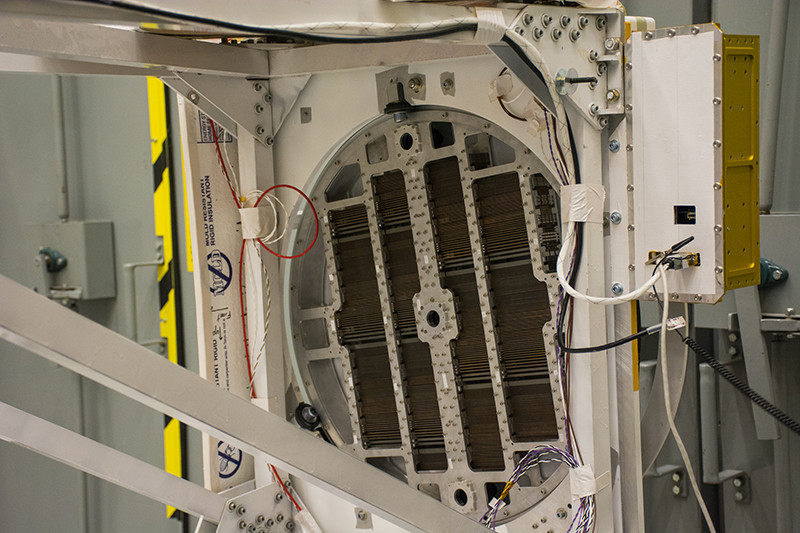

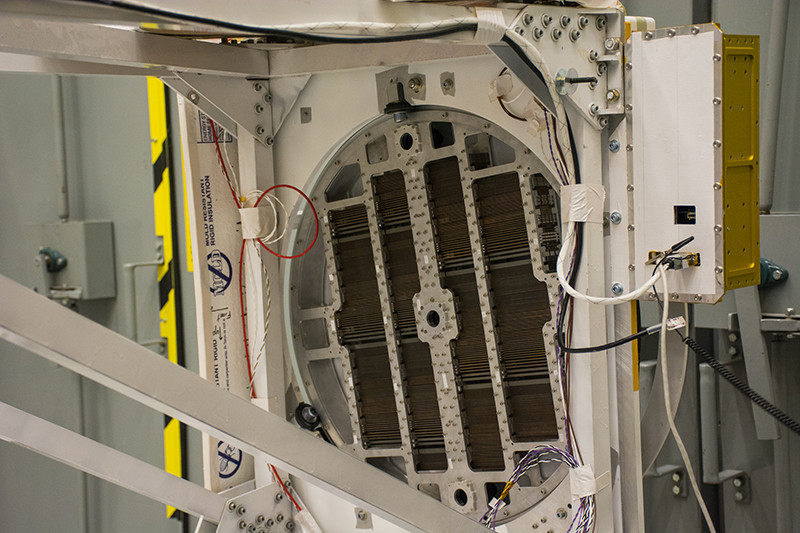

At the end of GRIPS’ eight-meter-long boom, the tungsten slats in the Multi-Pitch Rotating Modulator, let scientists pinpoint the exact source of gamma rays while they’re observing the sun.

The researchers working on GRIPS are hoping to use the data they collected to shed more light on how these solar flares accelerate charged particles up to nearly the speed of light both on our own sun, and on astrophysical objects throughout the cosmos.

Photo Credit: Mike Lucibella

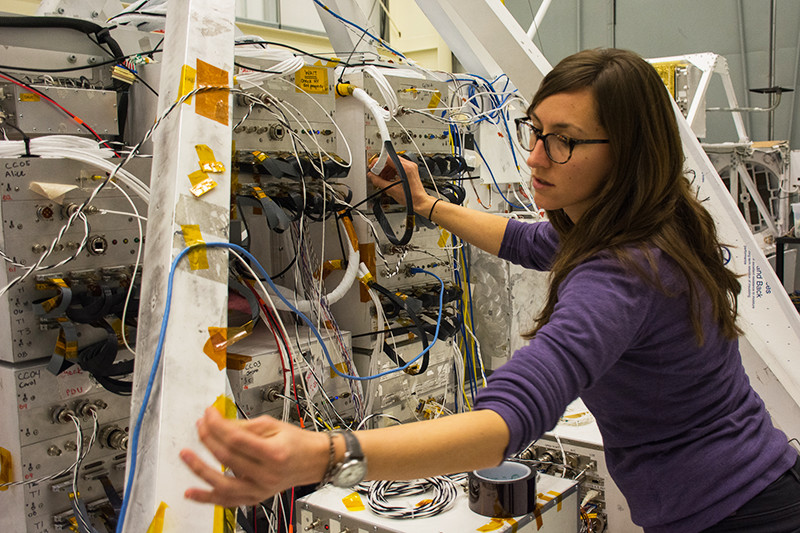

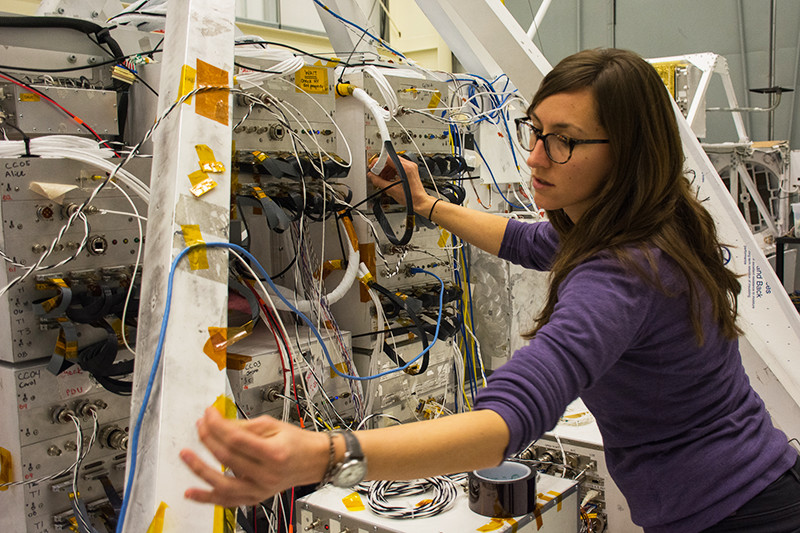

Researcher Nicole Duncan checks the wiring on GRIPS before its flight.

“Understanding what’s happening on the sun, how it can accelerate particles so efficiently, helps you understand those more exotic objects, and also helps us understand solar flares which means how to better predict them,” said Pascal Saint-Hilaire of the University of California, Berkeley and principal investigator of the project.

The science team is focusing in on an aspect of these flares that hasn’t been studied in depth. Electrons dominate the emission from solar flares, but these flares also accelerate ions, the charged nuclei of atoms that have had their electrons sheared off.

“When particles are accelerated on the sun, both electrons are accelerated and ions are accelerated, but the ion side is actually, relatively speaking, poorly observed,” Shih said. “We’re trying to push the technology, push the observations, to really understand what is going on with ion acceleration in solar flares.”

Previous

1

2

3

4

Next