|

Cool artPolar Artists Group raises awareness about climate change in Antarctic, ArcticPosted March 21, 2008

When raising awareness of the polar regions and the effects of climate change, artists can sometimes reach a wider audience than scientists. More Information

To learn more about the Polar Artists Group and to find links for all these featured artists and others, check out the Polar Artists Group Web site

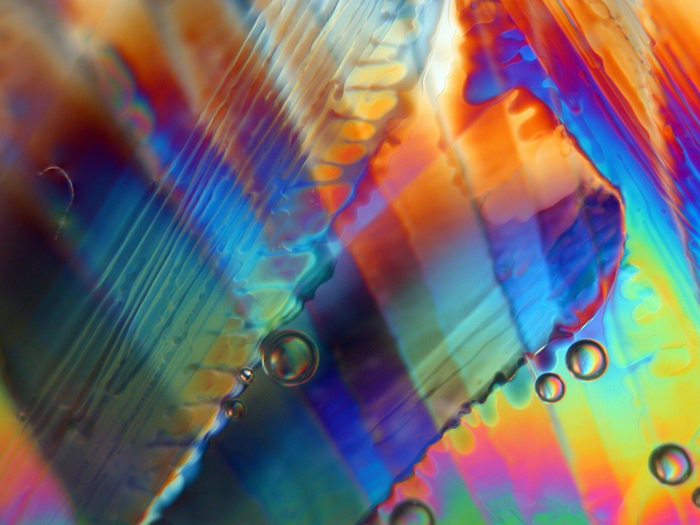

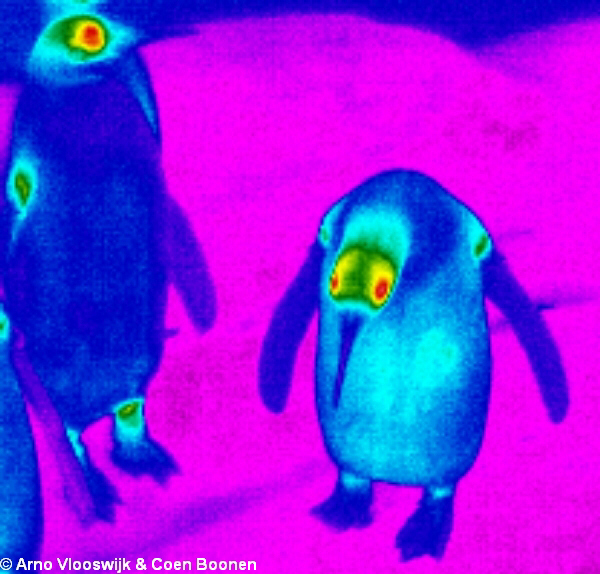

“The public has a strong affinity for polar icons and imagery,” says David Carlson, director of the International Polar Year (IPY) from his office in Cambridge, U.K. “We need both an intellectual response and an emotive response to help people acknowledge the climate changes and recognize the need for societal change.” Responding to that need, Canadian painter Linda Mackey co-founded the Polar Artists Group two years ago. Coordinating with the IPY, most of the group’s 50 artists, photographers, writers and filmmakers have traveled to the Arctic or Antarctic to create art to capture life in these extreme environments. “We realized there was a need to bring artists and scientists together, so as a group we can open the eyes of the world to the changes occurring,” says Mackey, a veteran of four trips to the Arctic, from her home in Ontario. “We have an amazing group of diverse artists. Whether it’s through painting, photography, writing or film, the more ways you can tell a story, the more people you can reach.” Maria Coryell-Martin is one of the sub-zero artists who strive to capture the beauty of polar and glaciated regions. A former artist-in-residence on two commercial expeditions to Antarctica, her paintings were recently featured during Polar Science Weekend at the Pacific Science Center in her hometown of Seattle. “I was overwhelmed by the immense scale and beauty of the Ice,” Coryell-Martin says of her trips to the Antarctic Peninsula. “Art serves as a visual record for our history, and I hope my paintings serve as witness to these environments.” Polar artists face special challenges in the field, such as paints and brushes freezing. “So I add vodka to my paints to lower the freezing point,” says Coryell-Martin, who admits she gets some gentle teasing from people who wonder whether it’s the art or artist that benefits most from the 80-proof solvent. She also had to learn how to paint with mitts on while combating wind and snow. Photographers, too, can sometimes find the brutal weather challenging. Photojournalist Chris Linder traveled to Antarctica last November on an educational outreach grant from the National Science Foundation (NSF). “The joy of being there far outweighs the photographic difficulties such as blowing snow, or keeping fingers warm and batteries alive,” he says. Accompanied by a writer, Linder followed polar researchers for a month and posted daily photo essays of his travels. “We wanted to go beyond the sound bites normally heard on the TV news, and tell a more complete story of how polar scientists conduct their research,” says Linder, who is also an oceanographer at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in Massachusetts. Amassing some 500 to 1,000 photos daily, Linder had to select eight photos each day for his writer to weave into a story to post on their Polar Discovery Web site Linder has traveled the world, including a half dozen trips to the Arctic, and says he enjoys the artistic challenge of polar photography. “Sometimes there’s not that much color to landscapes, so you really have to think like a black and white photographer in terms of shapes, shades and lines when composing a photo.” Color can be found, however, in surprising places. The huge Antarctic penguin population can create a carpet of pink droppings after feasting on a diet of krill. And “colorful” icebergs are actively sought out by photographers like Camille Seaman. Seaman’s stunning photographs highlight the eerie, neon-blue hue of the icy monoliths on their irreversible journey to ultimate destruction, as time and the elements slowly erode them. Not unlike humans, the Berkeley artist says, the icebergs have been created by a unique set of conditions, shaped by their environment to live brief lives in a manner solely their own. “Blue” icebergs, which usually break off from glaciers composed of denser ice, are best photographed on overcast days, according to Seaman. “When the sun comes out, the icebergs just go white and lose their personality,” says Seaman, whose photo exhibit “The Last Iceberg” will be on display at the National Academy of Sciences in Washington from March through June. While studying the properties of ice on several continents, Peter Wasilewski also discovered art in ice, although on a smaller scale. An astrophysicist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md., Wasilewski says he uses only “ice, the laws of physics, and attitude” to create colorful abstract images of ice crystals through the polarized lens of a microscope. With six Antarctic expeditions behind him over the past 25 years, and honored with an ancient volcano that bears his name, Wasilewski discovered ice crystal art in 2001 while conducting a science camp for teachers at Lake Placid, N.Y. “We were taking core samples of the frozen lake surface and examining their crystal structure,” Wasilewski explains. While studying the frozen bubbles of methane produced from the decay of organic debris, he realized that color and form could change depending on the thickness and orientation of the ice. “I started playing around, making ice crystals in my refrigerator and photographing them.” While ice may fascinate Wasilewski, Arno Vlooswijk and Coen Boonen’s artistic interests lie in a warmer realm. Based in Holland, they create enchanting thermographic images of animals. Depending on an animal’s composition of fat, feathers and fur, the long-wave infrared radiation released as body heat results in a dramatic, colorful portrait of the animal’s surface temperatures. “It’s like holding 80,000 thermometers in front of an animal,” says Vlooswijk, who has captured thermal images of numerous species including penguins, polar bears and walruses. The Dutch Science Council recently nominated one of his images as an example of using science and art to reach a broader audience. “I look at the collection as educational resource material,” Vlooswijk says. “We can learn a lot from the thermo-regulating champions in the polar regions. And respecting their habitat is like creating the best classroom of the world for future generations.” The NSF recognized years ago that artists could sometimes reach a wider audience than scientists, according to Kim Silverman, program director for the NSF’s Artists and Writers Program. The program, unaffiliated with the Polar Artists Group, has sent about 80 artists, writer, photographers and others to the Ice in the last 20 years or so, and its roots goes back even further. (See related story: A Different Perspective.) “NSF recognized [the value of the arts] way ahead of many other organizations that later followed suit,” she said. Vlooswijk and the other polar artists plan to continue their commitment to bridge fine arts, science and education. They hope their diverse range of visual images will inspire others to voice their concern for the planet’s future. Nick Thomas is a freelance writer and teaches at Auburn University Montgomery, in Alabama. |

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsU.S. National Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |