|

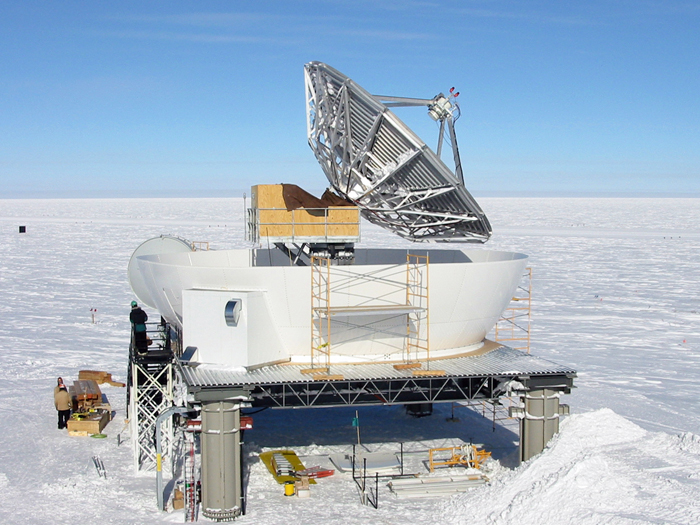

The MacGyver solutionPolies fix satellite dish with do-it-yourself solution to re-establish important communications linkAugust 29, 2008

Some folks down at the South Pole are in line for a MacGyver award after fixing a satellite communications dish that helps connect the isolated research station to the rest of the world. “It was really … amazing” that they could repair it, said Henry Malmgren, South Pole IT manager, of the do-it-yourself solution that a team of mechanics and technicians down at the station developed. In mid-July, the gears that move a nine-meter-wide dish up and down to track two of the three satellites that provide voice and Internet communications to the station literally grounded to a halt. To help solve a recurring problem, personnel had tried a new type of grease that was supposed to retain consistency in temperatures down to negative 150 degrees Fahrenheit. “It turns out that it doesn’t,” Malmgren said, noting that it turned to a solid at negative 50 degrees or so. Temperatures at South Pole can plunge to below negative 100 degrees Fahrenheit, though the satellite dish is located in an enclosed but unheated radome. Basically, the gears were moving without lubrication, according to Malmgren. “It chewed it up pretty good.” Without the dish, the communications window at South Pole Station Dana Hrubes, science lead at the station and one of two researchers maintaining the South Pole Telescope (SPT) “One reason is that we frequently have the need for one of our team members in the States to log on to one of the SPT computers here at Pole to upgrade and debug software,” he explained via e-mail. “Being able to do this in the most timely manner allows us to resolve problems more quickly, helping to maximize telescope observation time.” Malmgren said communications between grantees isn’t the only thing affected. “Morale is a big part of it, and just any kind of general communications. Meaning the time available for voice calls and e-mail was also reduced. You have to go back to Iridium, with reduced quality.” The Iridium connection does allow for small e-mail messages to squeeze through 24 hours a day. James Travis, the station’s utility technician supervisor, and Pete Allen, the satellite engineer, first tried troubleshooting the problem. They then recruited Jack Sharp, the vehicle maintenance facility supervisor, and Jason McDonald, a heavy equipment mechanic, to the cause. Sharp said by e-mail that as soon as he heard the noise coming from the antenna drive’s motor he knew the problem was with the bearing. They were able to isolate the problem to the jackscrew assembly, which controls the vertical movement of the dish. “We took the right side bearing cap off … and could see the bearing moving on the shaft. To kind of make it short, we didn’t have any parts down here that would fit it. I took the jackscrew apart just to see what we might be able to do with it. “[I] then decided I might be able to work some magic on it and just maybe get it running,” he continued. “I cleaned it up the best I could, changed some things around inside it to get a different wear pattern on the gears. I made up a different lubrication for the gears to run in, [and] put it back together. “We installed it, and it still seems to be working fine, and I hope it will ’til they get the new parts for it this summer,” he added. “No guarantees.” Said Malmgren, “It sounds great. It works perfect. We think it will last until the summer when we can replace it.” Sharp said he had never fixed anything quite that big before, though he had worked for a satellite TV company for a short while. “Being a mechanic, at least the way I am, I don’t seem to be able to let things go ’til I give it my best shot on a repair,” he said. “When I was drag racing, I would work on a problem for hours, even days, ’til I either solved it or couldn’t do any more with it.” The conditions under which the repairs were made make the feat even more impressive, according to Dennis Gitt, director of Information Technology and Communications for Raytheon Polar Services “It should be remembered that all the activities … were conducted in temperature conditions within the antenna shelter that approached minus [60] degrees Fahrenheit,” he said. A first-time winter-over, Sharp had a philosophical view of working in such extreme cold. “So far, this is a great experience to be down here — once you get used to the cold, working in the dark with a wind chill of minus 130 below. Your glasses freeze in less then three minutes … Ha: not a bad place to work; everyone should try it at least once for the experience.” |

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsU.S. National Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |