|

Night visionAir Force successfully tests new capability to fly any time of year to McMurdoPosted September 26, 2008

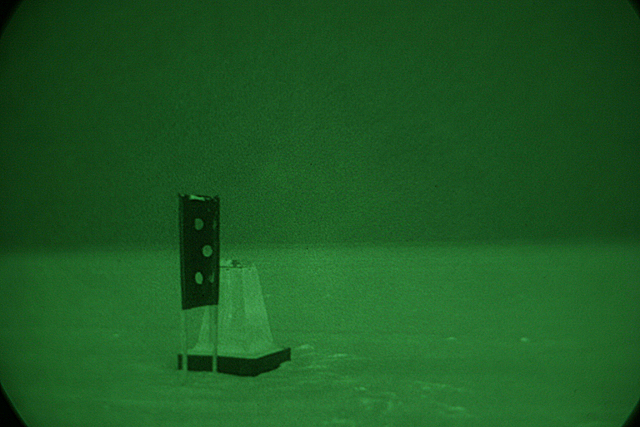

It’s been nearly 80 years since Adm. Richard Byrd made his famous flight over the South Pole, enough time surely for all aviation firsts to be inked into the record book. But a U.S. Air Force crew out of McChord Air Force Base “A little tired, but we got it done — kinda happy,” McGann said shortly after returning to Christchurch, New Zealand, where the 12-hour, roundtrip flight originated. Christchurch serves as the jumping off point to the white continent for much of the U.S. Antarctic Program “It was challenging, but it proves that we can get there when we need to. That’s what we were hoping to do,” McGann said. “The weather was not the best; honestly, it was right down to our minimum [cloud ceiling] of 3,300 feet. “It’s a revolution in Antarctic logistics, in that it allows us to get in anytime to do science,” he added. “It’s not just about doing medical [evacuations]. If people want to get in there and do a 30-day project, and NSF wants us to get in and out, we can do that now. We can do it safely. That wasn’t possible before.” During the austral summer, the continent enjoys 24-hour sunlight. In winter, a dark and cold curtain falls over Antarctica from about April to August. That’s when this new capability could potentially be used, whether to support winter science activities, or the rare but risky mission to perform a medical evacuation. “Before, the risks were so high that the needs had to be dire — there had to be an emergency,” McGann said. “Now we can get in there in what I would term a routine basis.” On the ground, personnel set up highly reflective cones along the runway to outline the airfield. The plane’s lights reflected off the cones, which the night-vision goggles picked up. Gary Cardullo, USAP airfield manager, said the landing was standard except that it took place in the dark. “I think the big thing was getting the reflectors put out that we use for the night-vision goggles,” he said. “It went flawlessly. No problems whatsoever.” It took airfield personnel only about half a day to set up the reflective cones, which were screwed into the ice. In the past, such a landing would have required the use of 55-gallon barrels of fuel, used like torches to outline the airfield. Electric and battery-powered lights don’t do well in the cold, when temperatures can plunge to negative 60 degrees Fahrenheit. “This process that we’re now using with the night-vision goggles and the reflectors is much safer to do. It’s easier to do,” Cardullo said. “It pretty much puts us in the 21st century rather than use old burn barrels to light things up.” Aircrew preparation and training for the mission began 18 months ago at McChord Air Force Base in Washington. Pilots, currently certified in NVGs, trained on a flight simulator. Ten of the 20-member crew on the Sept. 11 flight were pilots getting their certification to fly night missions to Antarctica. All had previously been to the Ice. “Down here, the certification was to fly a low approach — not a touch down but a low approach — seeing the cones utilizing the goggles and then that certifies you to be an NVG pilot,” McGann said. Cardullo said the C-17, a huge military cargo and troop transport used by the Air Force for missions around the world, made eight approaches during the training exercise. “It’s a lot different for a lot of folks. This is the first time we’ve ever landed a C-17 in the dark. It’s never been done before down here. It was just another first for the USAP,” he said. The night mission marked the fifth and final flight of SpringFly, for spring fly-in, roughly a weeklong operation that moves people and materials to and from the continent in preparation for the summer field season, which begins in early October. In the past, the operation was called WinFly (for winter fly-in) and took place a couple of weeks earlier, using a temporary runway on the sea ice near McMurdo Station. The NSF decided to push the operation back to cut costs in a tough budgetary environment. It has curtailed or deferred various operations and science projects for the upcoming fiscal year to keep the program in the black against rising fuel costs and a flat-lined budget into 2009. [See related story: Budget freeze.] The weather mostly cooperated during SpringFly, though one flight was delayed by about 24 hours, according to McGann. The week was similar to those in past years, though the temperatures on the ground were a little warmer, he said. “It was about minus 30 [Fahrenheit] or so; usually, we see minus 40 or 50.” The McChord aircrew returned home the day after the night mission. It will be a short homecoming: The team will return to Christchurch in 10 days to begin the summer season. This year’s work will include a training airdrop over the South Pole, the third time in as many years. The Air Force will also do four airdrops of fuel for a deep-field science project in East Antarctica. McGann praised his crew in the air and the personnel on the ground for a successful week, culminating with the historic landing. “To make it happen, to be part of it, is really what it’s all about,” he said. “The excitement, the exploration, overcoming obstacles. It was really fun doing something that was a first-ever in aviation.” |

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsU.S. National Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |