The long viewBartalos recycles Antarctic rubbish into artwork about conservationPosted April 17, 2009

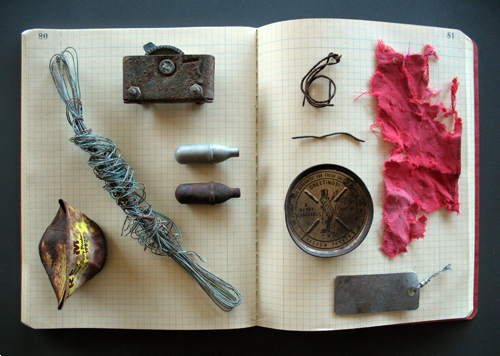

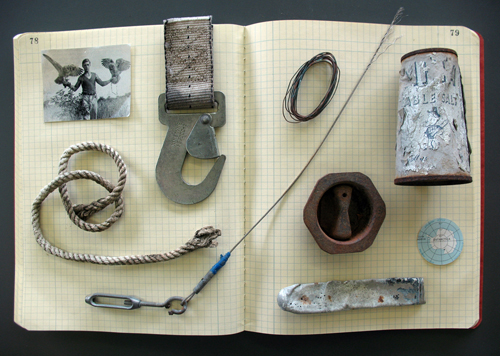

There’s a saying that goes, “One man’s garbage is another man’s treasure.” Michael Bartalos A San Francisco-based graphic artist, Bartalos recently returned from a trip to the Ice on a National Science Foundation Antarctic Artists and Writers Program In a recent e-mail interview, Bartalos discussed his inspiration for the project and explained the concepts shaping the piece. Antarctic Sun: What interested you in doing a project about recycling in Antarctica? You mention Ernest Shackleton’s recycling of wooden covers from provision cases into shelving and book covers in your project blog. Why did you find that inspiring? Were you already a fan of Antarctic history, or was that something that developed as this project matured? Has your previous work focused on conservation? Michael Bartalos: A number of my ongoing interests led to this project, namely in science, exploration, environmental and sustainability issues, and making art from found material. Shackleton’s recycling of wooden cases especially fascinated me as an early instance of polar recycling, and for its role in Aurora Australis, the first book edition created entirely in Antarctica. As a printmaker and book artist, I was compelled to pay homage to Shackleton’s legacy of resourcefulness on the centenary of the book’s creation, bringing Antarctic art-and-recycling back around full circle. I’ve been a long-time fan of polar science and history, and have created two Antarctic-themed art projects before this one. The first project was a multimedia piece titled Polar Book Lab for a Xerox PARC artist residency. The second was an artist’s book edition titled Vostok that speculates on life in the subglacial lake located beneath the Russian research station of the same name. The Long View project, however, is my first to be created on an NSF grant. AS: What’s the final project going to look like? You describe it on your blog before heading south as a freestanding, accordion-style book made up of 100 vignettes. Is that still the plan? Could you give me some examples of a vignette? MB: The plan is still to do a string of 100 vignettes. I’d describe these vignettes as relief sculptures mounted on upright panels, approximately 9" x 12" each. They will be mixed-media pieces comprised of wood, wire, paper and hardware, strung together to reference a book structure, in turn alluding to Aurora Australis. The material I collected and shipped home from Antarctica just recently arrived, so I’m still deciding how best to incorporate it into my artwork. I’m also still deciding whether to stand the string of vignettes on a flat surface or hang them on the wall. I’ll be resolving these issues as I construct the vignettes. AS: How did you decide what to collect for your project and how did you collect your material? It seems like many people were eager to pass on their "junk" to you for the project. MB: My intention was to collect material that was uniquely Antarctic; artifacts that described the polar experience, past and present. I succeeded in this, but in quite a different way than I’d expected. I originally assumed that Skua [a building used to freely exchange items in McMurdo] and the Waste Barn would be my principal resources, but most of the trash there turned out to resemble the contemporary U.S. waste stream too closely to make it worth collecting. I knew there must be exquisite discards somewhere, but I didn’t know where or how to find it. Then, as word of my project spread, people started offering me cool stuff they’d collected over their seasons on the Ice. Some of it came from the [Berg Field Center] and Crary [Laboratory]; some came from more remote areas. Much of it was picked up off the ground in the Dry Valleys; metals, bottles, cans, hardware, and wire strewn about in decades past, before the Antarctic Conservation Act prohibited such littering. Randall “Crunch” Noring, the Marble Point field camp manager, was an exceptionally generous donor of exquisitely weathered artifacts he’d found around his station. Others contributed torn flags and tent fabrics that evidenced Antarctica’s elements; others offered discarded maps and charts that describe polar research. In all, 16 people contributed, and I’m grateful to them because most of their items have more character and significance than anything I was able to scavenge myself. The aged relics are especially great for adding an element of environmental history to the project while complementing the recycling theme. Despite collecting little from the Waste Barn, I came to understand its importance to the USAP recycling system and enjoyed documenting it for my project blog’s audience. Researching waste management operations at McMurdo, [South] Pole and the Dry Valleys was integral to my project, which, again, I couldn't have done without the help of folks like James Van Matre and Steve Kupecz and many others. As you see, it all shaped up to be a collaborative effort, and I couldn’t have asked for more enthusiastic and informative participants. AS: In your blog, you note some of the art and artistic and musical events around McMurdo. Were you surprised to find such a healthy little art community in Antarctica? MB: Yes, it was a very pleasant surprise that made me feel right at home. I was so impressed by the degree of artistic passion brought to [McMurdo Alternative Art Gallery] and the music performances, not to mention the inconspicuous public sculptures, signs, engravings, and quirky installations around town. McMurdo is practically a metaphor for the greater co-existence of art and science. I better understand this phenomenon now, having experienced Antarctica as at once a clean slate and an endless source of inspiration. AS: I’ve referenced your blog a couple of times. You’ve really created a very detailed record of your trip, thought process, etc. Is this something you normally do, or is this the first time you’ve documented an artwork like this in the public view? What do you think of this sort of public discourse in the development of a piece of art? MB: I often keep travel journals and take loads of photos for my own reference, but this is the first time I’ve documented my creative process online. I like it. It’s exhilarating and motivating, and I find that articulating my thoughts helps determine my creative direction. So the blog has really become as much an element of the project as the finished art will be, which [is] pretty cool. AS: Do you think your trip to Antarctica will have any long-lasting effects on your art? If so, how? MB: Oh yes, like all my memorable trips, this one has provided inspiration and source material for many projects to come. I'm pretty impressionable that way; my travel experiences and observations heavily influence the color, texture, and compositional choices I make afterwards. I’m now actually giving white space in my compositions more consideration than before, and I'll never work with wood again without thinking of Shackleton's recycled cases at Cape Royds. AS: What’s your timeline and plan for creating and showing the final project? MB: It will take a few months to create the hundred vignettes. … I’m hoping to have them done by year’s end. They’ll be exhibited at a San Francisco venue to be determined, and there is out-of-town interest as well. The final art will also certainly be showcased online where it will find the widest audience, namely on my California Academy of Sciences blog and my own Web site NSF-funded research in this story: Michael Bartalos, Award No. 0739945 |

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsU.S. National Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |