Long time comingWomen fully integrated into USAP over last 40 yearsPosted November 13, 2009

Ernest Shackleton placed perhaps the most famous job wanted ad in history for his 1914 Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition, which later earned him so much acclaim for the hardships encountered and overcome. The advert read: “Men wanted for hazardous journey. Low wages, bitter cold, long hours of complete darkness. Safe return doubtful. Honour and recognition in event of success.” More than 50 years later, when the Antarctic Age of Exploration slipped into the Age of Scientific Discovery, the job ads for forklift drivers or even administrative clerks may not have dripped with such machismo. But there was no less swagger to the attitude that still dominated on the continent when the first female scientists arrived in 1969. It wasn’t too long after the ranks of researchers opened up to women that they started to fill support roles — first in the U.S. Navy and then increasingly among the civilian workforce that eventually took over most jobs today from the military. Elena Marty was one of two female employees hired by civilian contractor Holmes and Narver Inc. for the 1974-75 austral summer season. It was the Antarctic equivalent of NASA “In that day, there was still a very big ceiling to break through. The fact that they were ‘allowing’ women to go to the Ice was huge. We were an anomaly and a commodity down there,” says Marty, now retired in Long Beach, Calif., with her husband Jerry, who was also an H&N employee at the time. (Jerry Marty later worked in the National Science Foundation’s Office of Polar Programs “That was a tough time for women who wanted to show they could do more than just file and type and take dictation,” she recalls. “I looked at this as an opportunity to explore more of what I could do in a remote location besides just being there. I was able to learn a lot there, as well as make contributions.”

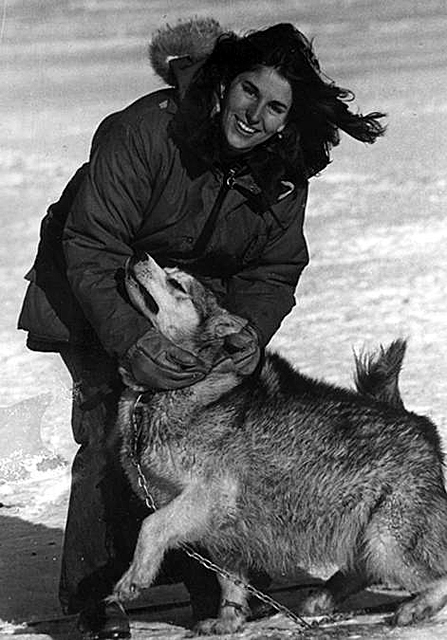

Photo Credit: Jerry and Elena Marty

Women like Elena Marty were a rare sight in Antarctica in 1974-75. Today, not so much, though dogs are prohibited on the continent.

Hired in an administrative role at McMurdo Station “They really didn’t put out an ad for women to work at the South Pole,” Marty notes. Half-a-dozen years later, in 1981, the ratio of men to women working in the U.S. Antarctic Program “It was a little rougher around the edges than it became later, say in the late 80s and early 90s,” recounts Peoples, who worked for the U.S. Antarctic Program for 14 consecutive seasons. She started as a shuttle driver and left in 1995 as the first woman to head one of the USAP’s three permanent research facilities at Palmer Station. Even into the 1980s, pinup posters of Raquel Welch hung on work center walls. Jobs for women were generally limited to driving shuttle buses, shuffling paperwork or pushing a mop as a janitor. Only a few women worked in the trades. “Since women weren’t viewed as being as strong, skilled, or competent for the entire range of job opportunities, that meant that the number of positions available to women before the late 80s were just so limited,” says Pam Hill, whom Peoples hired in 1985. |

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsU.S. National Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |