Behind the scenesColin Bull recalls his 10-year quest to send women researchers to AntarcticaPosted November 13, 2009

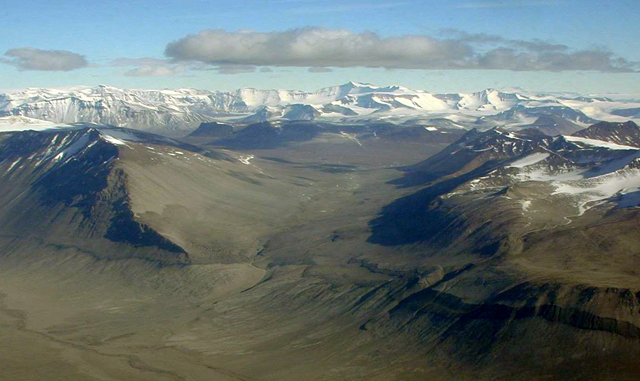

[Editor’s note: Colin Bull took the first university-sponsored expedition to Antarctica from New Zealand in 1958-59. The following year, Victoria University of Wellington wanted to send another research team, a decision that eventually led to Bull’s 10-year quest to send a woman scientist to the Ice.] I said I’d organize a second expedition but wouldn’t be a member, because my daughter Rebecca was due to be born at Christmas in 1959. Dick Barwick, Bob Clarke and I decided that the expedition should work mainly in the western part of Victoria Valley in the McMurdo Dry Valleys, with a main camp near Lake Vashka, and with three or four subsidiary food caches around the area. Bob and I went to New Zealand’s Scott Base Second in command would be Ralph Wheeler, lecturer in geography, and two students in geology, Graham Gibson and Tony Allen. And then we waited and waited and waited for the fifth person to volunteer — we didn’t pay anyone in those days. A tiny tap came on my door in the Physics Department one day, and a little pixie face came round the door, and a voice said, “Do you think I could go to Antarctica?” She was Dawn Rodley, a geology student, who had made first ascents in the Mount Cook area and did long traverses in the Tararuas Range in New Zealand. Great! Except that she was female, and no female scientist had ever been to the Antarctic. So I jumped at the wonderful opportunity that Dawn represented. Our little university might make a great step forward in the social development of the whole world! We asked the four others of the expedition what they thought of the idea of having Dawn as the fifth member — and that went well. And the wives of Ron and Ralph approved. The university jumped at the idea, and so did the Ross Dependency Research Committee, the official Antarctic Committee of the New Zealand government. I lived next door to Ted Thorne, the senior ship captain in the New Zealand navy, and one Sunday lunch, as we were sipping our sherries, I told him what we wanted: transport to and from Scott Base for our five-person expedition, including Dawn. He couldn’t see any difficulty. Great! All we needed now was one hour of helicopter time to fly Dawn and the others from Scott Base to Lake Vashka. The U.S. Navy, in charge of Operation Deep Freeze for the burgeoning American research program, adamantly refused. I tried and tried. I tried to get New Zealand Prime Minister Walter Nash and the U.S. ambassador to New Zealand involved — all to no avail. The Navy was getting cross with us, so I became scared that they might refuse to take over the male members as well. So Dawn, bless her, resigned from the expedition and was replaced by Ian Willis — and they all went off and did a great job. The refusal of the U.S. Navy to take Dawn struck me as being so ridiculous that I tried for most of the following 10 years to get a woman scientist included in one of our parties. In 1961, our family moved from New Zealand to the Institute of Polar Studies at The Ohio State University That’s when Mort Turner, program manager for geology at NSF, called me and said, “The Navy has relented. You can send a four-female party — as long as they all have Antarctic experience.” Well, we just regarded that as an extra challenge, and we satisfied them. The leader was to be Lois Jones, built like a Sherman tank, and with a recently completed PhD on chemical ratios in Antarctic rocks. That’s obviously “Antarctic experience,” isn’t it? Second in Command was to be Kay Lindsay, a biologist with a master’s degree in science and wife of John Lindsay, a geology PhD student who had been to the Antarctic several times. So Kay had “Antarctic experience” waiting for John to come home. Exactly the same applied to Eileen McSaveney, graduate student in geology and wife of my PhD student Mauri McSaveney. The fourth young lady was a chemistry undergraduate, Terry Tickhill. We were never able to invent any Antarctic experience for her, but she was good at stripping down a motor bike, or a radio, or a primus stove — just what you need in a small Antarctic expedition. Well Lois and party, working mainly in Wright Valley, did a good job. They made about the same number of mistakes as a party of four neophyte males would have made — no more. One of the surprising results of my efforts to liberate a whole continent for women was the reaction of some of my male friends. One chap, who had been at South Pole Station After that, we had little or no difficulty including females in our scientific parties. Today, the U.S. Antarctic Program Colin Bull, geophysicist and glaciologist, was a senior lecturer in the Victoria University Physics Department at the time of his 1958-59 expedition to the McMurdo Dry Valleys |

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsU.S. National Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |