Lake Gorita?Bull admits he is all wet over the naming of Lake VandaPosted January 8, 2010

What’s in a name? In the case of Lake Vanda, a super-saline lake in the McMurdo Dry Valleys And The Antarctic Sun has the exclusive scoop, thanks to a recent interview with pioneering polar scientist Colin Bull. Bull was one of four members of the first university-sponsored expedition to Antarctica during the 1958-59 field season, back in the day when the continent was almost geographically and scientifically a blank slate. He recently published a book on the experience, Innocents in the Dry Valleys (Victoria University Press, 2009). That season Bull and his companions — Dick Barwick, Barrie McKelvey and Peter Webb — established their main base of operations near the shore of Lake Vanda, which was nameless at the time. During the previous year, the Victoria University scientists had worked in Victoria Valley. Webb had named two of the valley’s prominent lakes, Lake Vida and Lake Vashka. Now, on the shore of the eight-kilometer-long lake in Wright Valley, the men decided it needed another “V” name. Bull recalled that the lead dog of the “only sled team I had driven seriously” during an expedition to Greenland in 1952-53 was called Vanda.

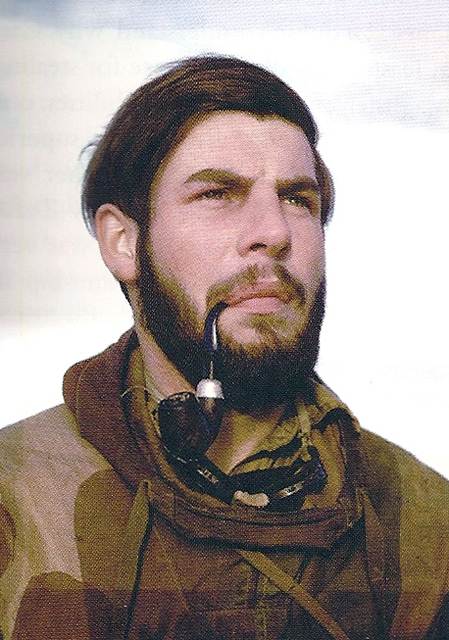

Photo Courtesy: Colin Bull

Colin Bull, 1958

The animal, Bull said, wasn’t particularly bright. On one dark night, Vanda had steered the entire team within a few meters of a tent and near disaster. However, no other suitable named presented itself, so Lake Vanda it was. But while recently poring over his Greenland journal, Bull was horrified to discover that Gorita and not Vanda was the dim dog of his sled team. There was a Vanda, but she was a slippery canine and evaded attempts to harness her to the team. “This is a real problem, because I’ve been living with this lie for 51 years,” Bull lamented. “Now what should we do? Change the name of the lake or the name of the dog? “The rest of the account is true,” he added. “Gorita wasn’t the most perceptive of dogs, but perhaps she deserves a lake namesake.” Lake Vanda — or Lake Gorita — is one of about a dozen perennially ice-covered lakes in the Dry Valleys, a relatively ice-free area near the U.S. Antarctic Program’s McMurdo Station Like nearly all the lakes in the valleys, Vanda has no outlet. Its level rises and falls with inflow from the Onyx River, which is fed by seasonal glacial melt. The surface ice insulates in winter and allows extensive heat transfer during the summer. The result is a water temperature near the lake bottom that averages around 25 degrees Celsius above zero. The lake also has a high saline content because salts fall to the bottom when the surface water evaporates. That means the surface is fresh while the layers near the bottom are more salty than the Dead Sea. Now history must add a new footnote to Lake Vanda’s list of peculiarities. “This is a friendly piece of warning: Never check up on yourself,” advised Bull, now retired on Bainbridge Island in Washington State’s Puget Sound. Additional sources in this story: The U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Natural Resources Conservation Service, “The Lake Vanda Swim Club.” Return to main story: Groundbreaking study.

|

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsU.S. National Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |