Page 2/3 - Posted June 25, 2010

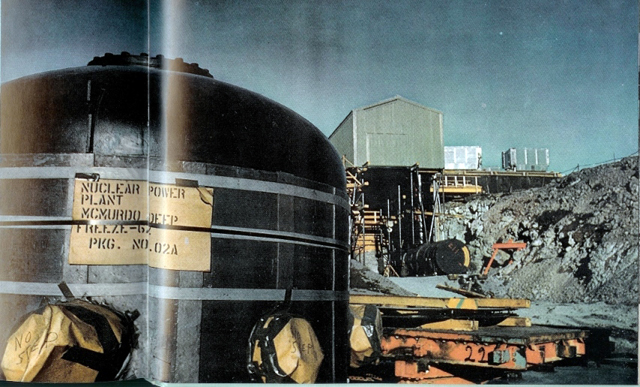

A unique experimentA nuclear power plant in the Antarctic was one of the unique experiments of the Army Nuclear Power Program (ANPP), which involved all of the military branches, to develop small, pressurized water and boiling water nuclear power reactors, primarily at remote, relatively inaccessible sites. In total, eight reactors or plants were built between 1957 and 1967 The military acronym “PM” stood for “portable, medium” output reactor. The number “3” represented the third such reactor in what had been planned as a series of small-scale nuclear power plants that the military could deploy for multiple purposes. The letter “A” indicates a field installation. The first in the PM series, PM-2A, became operational in February 1961 at Camp Century, a buried station 150 miles east of Thule, Greenland. The second, PM-1, a sister plant to the PM-3A in Antarctica, became operational in June 1962 in Sundance, Wyo., at an Air Force radar station. Fegley, a 25-year Navy captain, had received part of his operational training on the Army’s nuclear power plants on PM-2A and at Fort Belvoir, Va. The men assigned to PM-3A were part of the Naval Nuclear Power Unit, a subcommand under the Naval Facilities Engineering Command. The initials NNPU were the source of the plant’s nickname “Nukey Poo.” Martin Company, now Lockheed-Martin, designed and fabricated the facility. The reactor equipment for PM-3A was shipped to McMurdo by vessel, but it was designed so that all components could fit inside a C-130 military aircraft for deployment to sites farther inland. Plans for two such reactor sites in Antarctica — the former Byrd Station and South Pole Station U.S. Navy Seabees completed site preparation and excavation for the facility during the 1960-61 summer season. Construction of the plant buildings and equipment followed the next year. The reactor first went critical on March 4, 1962, and began producing power on July 12, 1962. Fegley was the officer in charge during the winter of 1964 when he formally accepted the responsibility for PM-3A on behalf of the Atomic Energy Commission Said Fegley via e-mail: “This really was an engineering and logistic achievement: new technology in a very hostile environment. It took the management and technical skills of a team of dedicated men to make it the success that it was. “It is a shame that the program was eventually dissolved, because the technology could have been improved upon and become useful in places like South Pole Station, where today the logistics of providing enormous quantities of fuel have almost become overwhelming,” he added. Shutting it downBy the early 1970s, nuclear power in Antarctica had lost a bit of its luster. The Navy and the rest of the military were busy fighting the war in Vietnam, meaning more and more of the management of the U.S. Antarctic Research Program, which later became simply the U.S. Antarctic Program A March 1980 article in the Antarctic Journal references a May 1972 cost-effectiveness study that recommended the power plant be shut down. It required 23 personnel to operate and its 72 percent availability, which was respectable at the time, required a diesel power plant to be staffed year-round as backup. Then, on Sept. 19, 1972, during a routine shutdown for maintenance, water was found to be leaking into the thermal insulation surrounding the primary (reactor) system, according to Fegley. Repair would have been an impractical and expensive proposition. The next 7½ years, until February 1979, were spent decommissioning and removing the facility, including about 11,800 cubic yards of radioactive dirt from the site in compliance with the Antarctic Treaty. In May 1979, the Department of Energy |

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsU.S. National Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |