Making historyGibbs first person of African descent to set foot on Antarctic continentPosted October 1, 2010

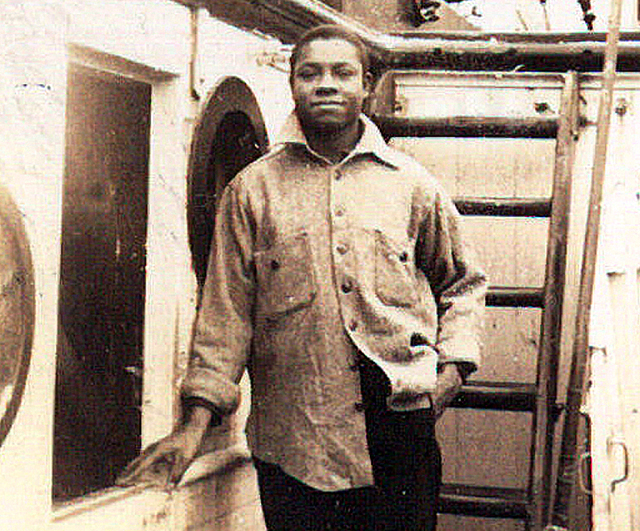

“When the Bear came up to the ice close enough for me to get ashore, I was the first man aboard the ship to set foot in Little America and help tie her lines deep into the snow. I met Admiral Byrd; he shook my hand and welcomed me to Little America and for being the first Negro to set foot in Little America.” So reads an entry in the journal of George Gibbs Jr., a 23-year-old Navy mess attendant who served in the galley aboard the USS Bear on Jan. 14, 1940, during Adm. Richard E. Byrd’s third expedition to Antarctica. It’s a special moment in Antarctic history, one few people know about — the first person of African descent to step foot on the continent proper. Leilani Henry For nearly 10 years, Henry has endeavored to bring her father’s story to print after he passed away on Nov. 7, 2000, at the age of 84. It was a project her father had attempted, though he had expressed doubts about ever finishing because he didn’t have enough information.

Photo Courtesy: Leilani Henry

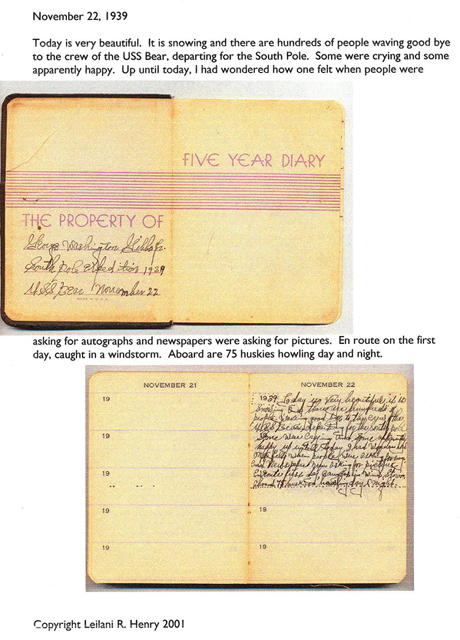

Pages from George Gibbs' journal with transcriptions by Leilani Henry.

No historian, Henry had her own doubts about taking up the memoir on behalf of her father. “I thought, ‘If you don’t have enough information, then what am I going to do?’” That changed a few months after his death when her mother discovered Gibbs’ lost journals from his Antarctic adventure hidden behind their bedroom dresser. Henry read through the slender notebooks and transcribed the journal. A long road of research began. “My father wanted to write a bestseller. He didn’t want to just publish his journals. My challenge is who is going to care about this story the most,” she says, echoing the dilemma of many an author. The narrative is still coming together — gaining steam in recent months as new sources turn up — but the lesson of the book is already clear to her. “You can make something of your life no matter where you came from or what happened to you. When you make something of your life, it can make a huge difference in the lives of many, many people,” says Henry, who lives in one of the many foothill communities just west of Denver, Colo. “It’s a human story about somebody making a difference,” adds Henry, a tall, lean woman with sharp and ageless features. Making historyGibbs was born on Nov. 7, 1916, in Jacksonville, Fla. He enlisted in the U.S. Navy in Macon, Ga., in 1935 and re-enlisted after his first four-year stint following some debate on what he wanted to do next with his life, according to Henry. Gibbs originally desired an assignment in Spain. Instead, he was encouraged to volunteer for an expedition with the U. S. Antarctic Service (USAS). An expedition jointly sponsored by the Navy, State Department, and Departments of the Interior and the Treasury, the adventure would more commonly be referred to as Byrd’s third Antarctic expedition.

Photo Credit: Michael Van Woert/NOAA

The Ross Ice Shelf at the Bay of Whales, near where Adm. Byrd established his series of Little America bases.

The mission was to establish two bases for scientific research. And that’s exactly what Gibbs and the other 124 men on the expedition did. West Base was established on the Ross Ice Shelf Two ships were used for the expedition — the USS Bear and the USMS North Star. The former was a 68-year-old wooden vessel originally commissioned for sealing — a precursor to today’s modern icebreakers. Its hull was reinforced with steel and a diesel engine installed for the Antarctic expedition. Every day from November 1939 to May 1940, Mess Attendant 1st Class Gibbs recorded the literal ups and downs of life aboard the refurbished Bear. Henry reads one entry during an interview with The Antarctic Sun that makes her smile: “Seamen of yester year often told me that in the old days they had wooden ships and iron men and that today they have paper men and iron ships. I had taken it as a joke, but after last night on the USS Bear, I was convinced that they were right. Everyone lost his food. Even I lost mine.” Gibbs worked long hours as the lowest rank aboard the ship. But his work ethic garnered commendations from his commanding office — not to mention the special attention of Adm. Byrd. He made two round trips to Antarctica before World War II interrupted and ended the polar adventure. “To be a part of history was very important for him,” Henry says. “It’s important history. It’s exciting. … I didn’t realize how important this was. I didn’t realize how many other people this story is connected to.” |

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsU.S. National Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |