Page 2/2 - Posted October 1, 2010

Making connectionsIn the 10 years since she took over the project from a St. Paul Pioneer Press reporter who had originally agreed to pen the memoir, Henry has learned much about her father’s passion and past from unexpected places. She tracked down the family of Harrison H. Richardson, a dogsled handler on Byrd’s third expedition and a friend to Gibbs, which offered her new information about her own father. She recently located 95-year-old Anthony Wayne, the last living member of Byrd’s crew from the 1939-41 expedition, living in Schenectady, N.Y. Wayne referred to Gibbs as the “cook” during their conversation on the phone, Henry says. More Information

Related story: Lifetime Recognition

Article “Here’s another perspective,” Henry says. “All of my life we were thinking he was the lowest rank on the ship, a lowly mess attendant. In the eyes of the other people, they didn’t know if he was chopping potatoes or making pie. That changed my whole outlook on this whole project — just that one piece.” Henry has also found support from veteran polar scientist John Behrendt Behrendt invited her to speak about her father at a meeting of the American Polar Society “I found his story interesting. … In my capacity as author of two Antarctic memoirs, I have been encouraging her to complete her book soon,” Behrendt says. Transcending raceThe 1920s and ’30s weren’t exactly a time of racial tolerance in the United States. Henry says the Antarctic expedition offered her father a way forward to a better life. He was motivated by the fact that there were so few opportunities for blacks in his day There may have been some racial tensions aboard the ship, Henry says, but most of what she read from her father’s journals and other sources indicated that the Byrd expedition was fairly harmonious. Wayne, a seaman on the expedition, told her everyone had to work together to survive.

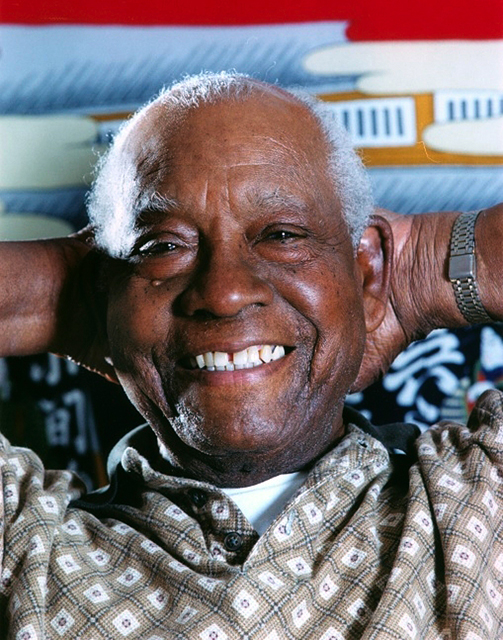

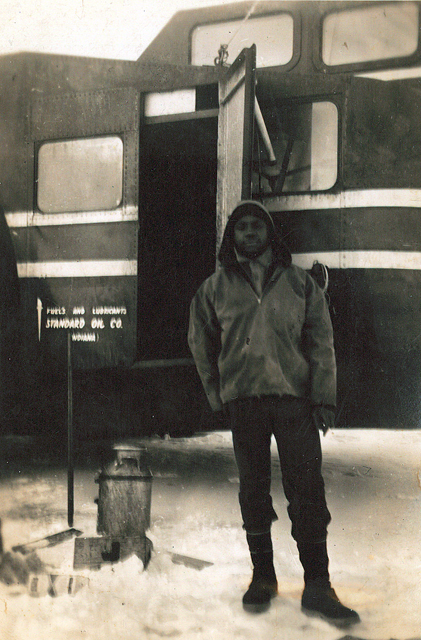

Photo Courtesy: Leilani Henry

George Gibbs Jr. poses in front of Adm. Richard E. Byrd's famous snowcruiser.

“Most of what happened transcended race,” she says. Gibbs was one of several African-Americans aboard the Bear — but apparently the first to step upon the continent. Though he wasn’t the first black man to sail to the Antarctic. That honor apparently goes to Peter Harvey of Philadelphia, who was a member of Capt. Nathaniel Palmer’s five-man crew during his 1820 voyage aboard the sloop Hero, according to an article in The Polar Times, the magazine of the American Polar Society. It’s also likely that many whaling and sealing vessels had black men among the crew. “While sealers landed on many of the peri-Antarctic [close to the Antarctic] islands, I know of none who reached the continent,” wrote R.K. Headland, a senior associate at the Scott Polar Research Institute “Similarly sealers recruited Maori and other Polynesians, and even occasional indigenes from Tierra del Fuego — but again I have no records of any reaching Antarctica,” he added. “Likewise, there were Africans on some of the whaling stations in South Georgia, but I know of none who went farther south. “If one keeps the details down to continental Antarctica then, as far as I have been able to find out … the earliest man of African descent to land on the continent was George Gibbs.” Making a differenceWhether or not Gibbs was first seems secondary in light of what Gibbs accomplished throughout the rest of his life. He gave 24 of those years to the Navy, including combat in the Pacific theater during World War II. He was on the USS Atlanta during the battle of Guadalcanal when it was destroyed by 49 shells and a torpedo. About a third of the 3,000 crewmembers died. Gibbs and the other survivors spent the night in the shark-infested waters before being rescued the next morning. Gibbs retired from the Navy in 1959 after rising to the rank of chief petty officer. He moved to Minneapolis, where he graduated from the University of Minnesota with a Bachelor of Science in Education. Gibbs then moved to Rochester in 1963 to work in the personnel department at IBM, where he worked for 18 years. After his second retirement, the tireless Gibbs founded his own employment company, Technical Career Placement, Inc., which he operated until about a year before his death.

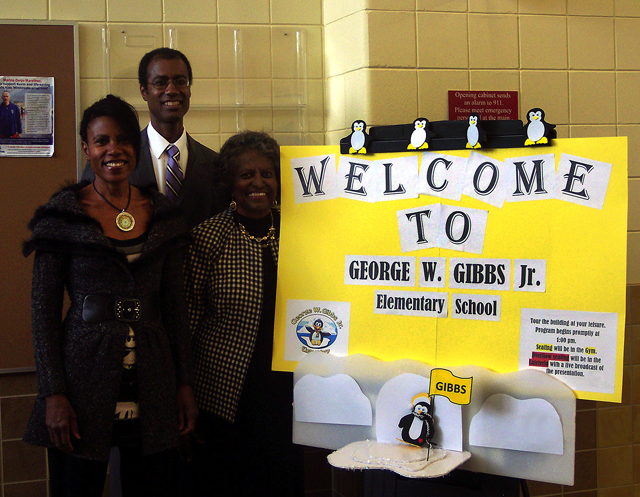

Photo courtesy: Leilani Henry

From left, Leilani Henry, her brother E. Anthony Gibbs and mother Joyce Gibbs at the dedication of a school named after her father in October 2009.

During the 1960s, Gibbs was active in the civil rights movement, co-founding the local branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and participating in protests. Only about 50 of its 350 members were black, according to Henry. “He’s very persuasive,” she notes. Gibbs was also active in his community, using his natural people skills to recruit his neighbors and friends to various causes. He never stopped talking about his Antarctic experiences. The community of Rochester honored his commitment to community by naming a school, street and scholarship in his name. In 2009, the Advisory Committee on Antarctic Names also recognized Gibbs’ accomplishments by naming a rock point on Horseshoe Island off the Antarctic Peninsula after him — Gibbs Point “The Antarctica trip was the background for him to understand that contribution was important no matter who you are and from what angle you’re doing it,” Henry says. “That’s what his life was about: Working for the community, getting people involved, looking at how everyone can make a difference.”Back 1 2 |

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsU.S. National Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |