Mountain lifeCTAM camp staff works behind the scenes to support sciencePosted April 7, 2011

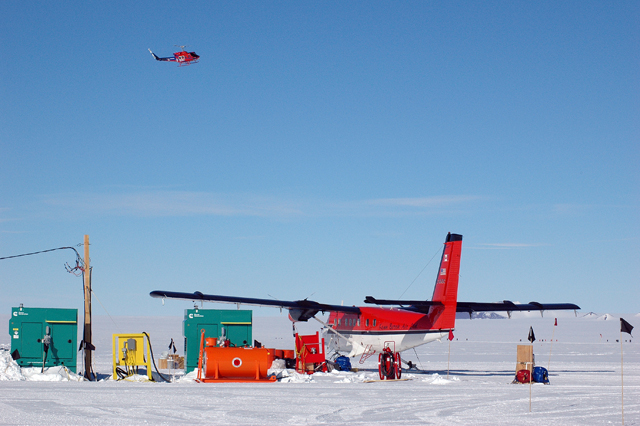

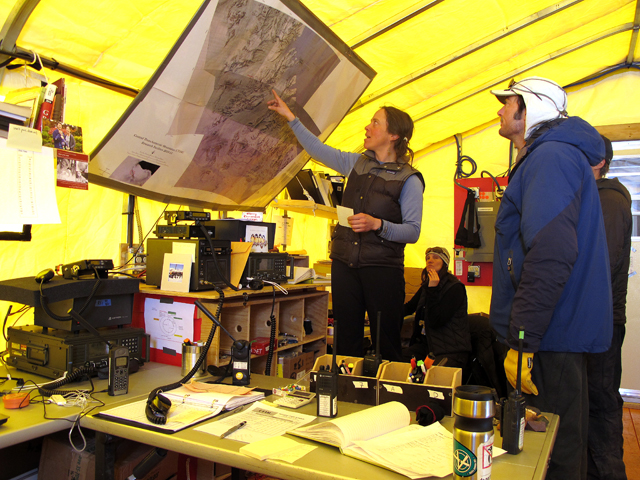

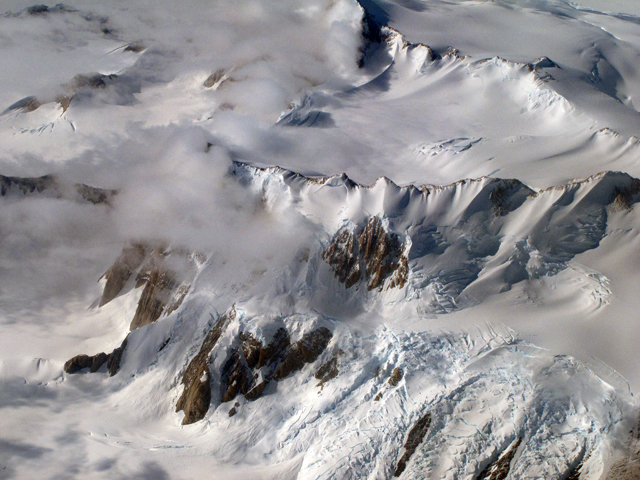

The central Transantarctic Mountains field camp may have been the busiest place south of McMurdo Station The silence that otherwise might have existed on a still, bluebird-clear day in Antarctica’s longest mountain range was often shattered by the clatter of two Bell 212 helicopters dropping down to land. The whine from the four props on a heavily loaded LC-130 attempting a takeoff joined the cacophony. Meanwhile, the faint hum from an approaching Twin Otter airplane added its own distinctive note to the aerial concert that occurred nearly every day at the largest field camp in the U.S. Antarctic Program (USAP) Yes, it was a hectic place. Eighteen different teams of scientists made their way through the camp over the two months that it was in full operation. The researchers were studying everything from dinosaur fossils to the ebb and flow of glaciers over countless millennia. Many spent weeks at the main camp, located just north of the mighty Beardmore Glacier, nearly 400 nautical miles from McMurdo. Some groups just passed though en route to more isolated spots that few, if any, humans had ever visited. All of them needed to hitch rides on an aircraft at one time or another. It was up to camp manager Julie Grundberg to schedule, reschedule, shuffle and reshuffle flight plans to get people in and out as weather allowed. “Every day is different. I’ve really enjoyed it. I’ll be sorry to see it end,” said Grundberg in early January, with a few weeks left before the sprawling camp would be packed up and flown north to McMurdo, the largest research station in the USAP. “I don’t get attached to any plan. Every day you just do the best with what you have, with the weather, with the aircraft, with the crews. It sometimes changes during the day and you adjust, and pick the best direction and go with it,” added Grundberg, a tall, sharp-featured woman who has worked for the USAP on and off for the last 10 years. This was her first stint at a field camp, let alone as camp manager. But her experience managing flight schedules in McMurdo made her a natural fit for this job. On Nov. 5, she and five other people were the first ones dropped off at the site. “It was basically a pile of tents and food and nothing else,” Grundberg said. A small army of carpenters would eventually follow, building science offices, a communications building, a long galley with a kitchen, among a host of other structures, in about 18 days. Enough facilities — including a shower — to accommodate about 80 people for short stints. A staff of about 18 people included cooks, mechanics, cargo handlers, dishwashers, and weather observers. “This is way too plush,” quipped lead cook Jake Schas, who commanded a tight kitchen, which sported a couple of household stoves, with two other cooks. Made-from-scratch cookies and cake could usually be found sitting above the DIY sandwich bar. Formerly a lead baker at McMurdo, Schas has found his niche in the field camps, preferring even more primitive conditions than one finds at the CTAM field camp. He previously spent two seasons on the polar plateau in East Antarctica, cooking on Coleman stoves for more than 40 people at an elevation of some 11,500 feet. Schas might have been more comfortable in some of the previous incarnations of the CTAM field camp, also referred to as the Beardmore camp. Most people will tell you there have been four Beardmore camps since the mid-1980s. David Elliot Today’s camp is definitely “grander” than those 40 years ago, according to Elliot, today a professor emeritus at The Ohio State University And while today’s scientists have limited e-mail access and Iridium phones for calls back to the United States, there are some things that no amount of luxury or technology will ever change: the fickleness of Antarctic weather. “You recognize that if you work down here that things may not work out as you intended. In fact, they very seldom do work out the way you intended. But that’s OK. That’s part of the game,” mused Elliot, 74, who served as chief scientist at the 1990-91 Beardmore field camp, which supported 15 science projects. There were also Beardmore camps during the 1985-86 and 2003-04 seasons. The camp also hosted an international meeting of dignitaries during the 1984-85 season. [See previous article: Mountain retreat.] John Isbell More importantly, the science coming out of the different groups is spectacular, he said. “Thanks to this camp, our understanding of the geologic and biologic history of this area is an order of magnitude greater than it was four weeks ago,” Isbell said. “We’re all small pieces of a much bigger puzzle. We’re each tackling something separate from each other. … You start building a history of the continent, piece by piece, sediment by sediment, or fossil by fossil.” If the scientists had any complaints it was that the camp would be only a one-hit wonder, pulled down even quicker than it was set up. Few believe there will be another camp near the Beardmore for years to come, meaning newly unearthed fossils may sit a long time before they can retrieved. Steve Hasiotis Still, the pony-tailed ichnologist was well satisfied with his haul of fossilized burrows and animal tracks. [See related article: No bones about it.] He credits his success in the field to those scheduling the helicopters and baking the bread back at camp. “We’re really indebted to the staff at CTAM because with those people doing the daily chores, there wouldn’t be a camp,” he said. Return to CTAM 2010-11 main page. |

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsU.S. National Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |