|

Arctic adventureMoriarty supported 1968 snowmobile expedition to the North PolePosted May 6, 2011

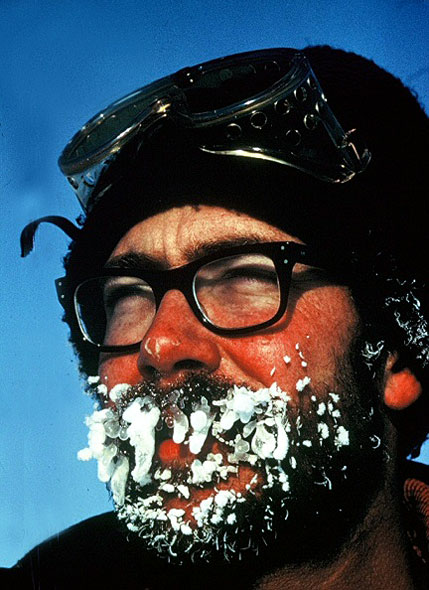

John Moriarty is one of those ordinary people who never seem to pass up an opportunity to do something extraordinary. In 1968, Moriarty’s sense of adventure propelled him to join a team of arctic adventurers that became the first to make an overland traverse to the North Pole using Ski-Doo snowmobiles, a relatively new invention at the time. Moriarty was a 28-year-old “food technologist” for the Pillsbury Company in Minneapolis, Minn., when a man named Ralph Plaisted approached the famous food manufacturer about supplying his upcoming arctic expedition with supplies. Moriarty was working in Pillsbury’s research and development (R&D) department. The lab had government contracts from the Army to develop foodstuffs for field troops, from freeze-dried meals to fruitcakes that could be baked in foil pouches. “They were just kind of weird, off-the-wall things. They were trying to develop better C-rations for the Army,” recalled Moriarty during an interview at McMurdo Station Plaisted knew about Pillsbury’s research through contacts at the company, Moriarty explained. An avid outdoorsman, with a mercurial personality, Plaisted and his friend Arthur Aufderheide (a physician who later gained fame as a pathologist specializing in mummies) had conceived of the idea of reaching the North Pole by snowmobile in the spring of 1966. Their first attempt in 1967 failed due to storms and open water. The attempt was captured in a CBS-TV documentary “To the Top of the World,” by Charles Kuralt, who accompanied the expedition. Moriarty had worked with Plaisted and his crew that year on food supplies. “I made some rations for them. I researched it by reading books I could find about mountain climbing and what they had for food. There wasn’t a lot of material out there,” Moriarty said. “Everybody seems to have relied on pemmican,” he added, laughing, referring an early type of energy bar made with fat and protein favored by such Antarctic explorers like Robert Scott and Roald Amundsen in their quest for the South Pole in the early 20th century. Plaisted decided to make one more attempt in 1968. Pillsbury again offered to sponsor the expedition with food. And so Moriarty got back to work developing a menu that incorporated about 5,000 calories per day. He even considered the logistics, assuming some of the food cargo might be airdropped to the field team. So he crated up a few boxes and dropped them off the third-floor roof of the Pillsbury building to see how the food would survive the crash. About two weeks before the expedition was due to depart, Moriarty approached Plaisted about joining the team. The group was still in need of a base camp mechanic to work on the diesel generators, along with other camp duties. “It was one of those things where you know you have to do it. I always wanted to do something like that,” said Moriarty, who had grown up reading the adventures of the polar explorers. “When you’re from Minnesota, you like the cold. I still like the cold. I figured this is my opportunity. If I don’t do this, I’ll never forgive myself.” The crew agreed Moriarty would make a good addition to the team, and on Feb. 21, 1968, he and the rest of the expedition members began the long journey to Ward Hunt Island, a tiny island off the north coast of Ellesmere Island where they would establish their base camp. It was used as a weather station during the International Geophysical Year of 1967-58, with a small, worn-out tented Jamesway building on the site. “It was up to us to make our own base camp, and that’s what we did,” Moriarty said.1 2 Next |

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsU.S. National Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |