|

Roof over AntarcticaNew book chronicles early exploration of Transantarctic MountainsPosted December 9, 2011

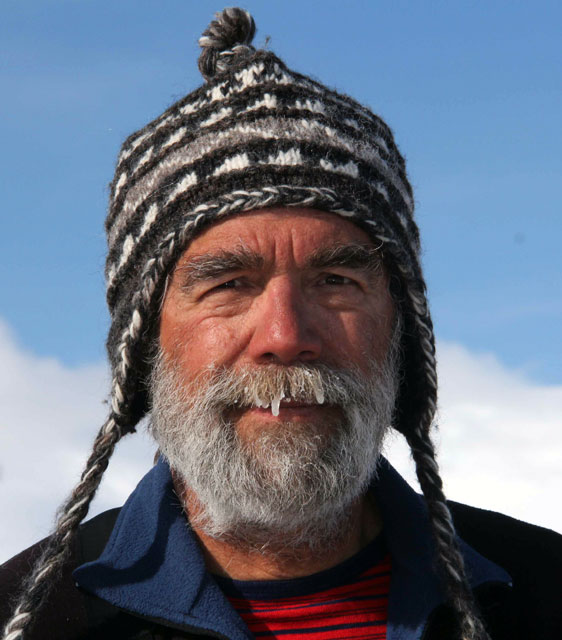

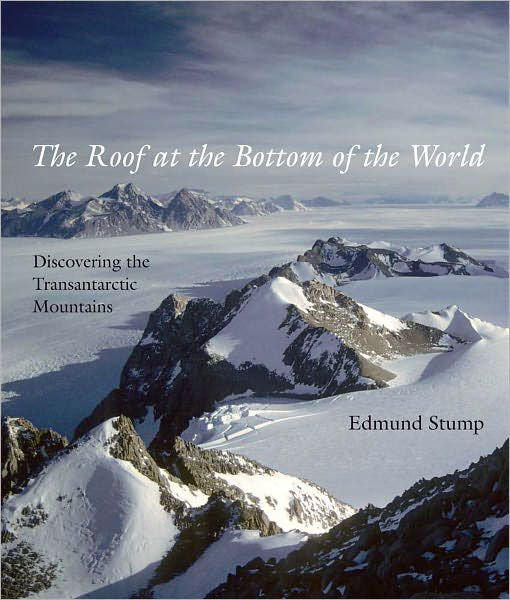

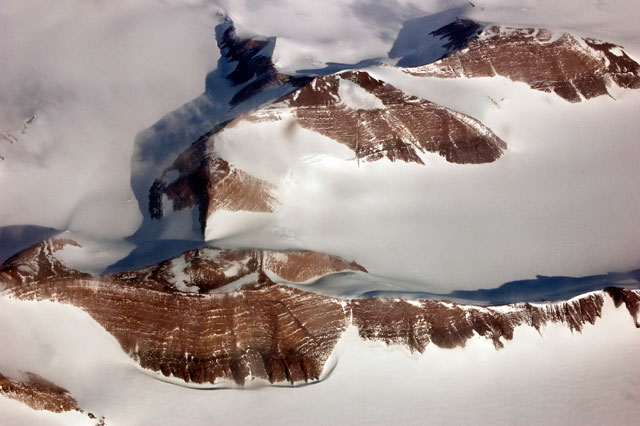

The Himalaya Mountains, the so-called Roof of the World, stretches some 2,400 kilometers across Asia, piercing the sky with more than 100 mountains taller than 7,000 meters. Equally as long, but virtually unknown outside the world of academia and polar adventurers, the Transantarctic Mountains (TAM) bisect the continent of Antarctica, separating its two great ice sheets. Few people alive today are as intimately knowledgeable about Antarctica’s great mountain range as geologist Edmund Stump “That season really changed my life and launched my career,” said Stump in 2010, four decades later, while back in Antarctica as chief scientist of a field camp in the central Transantarctic Mountains, which had become his home away from home. It’s only natural that Stump would write a book about his beloved mountains, The Roof at the Bottom of the World: Discovering the Transantarctic Mountains Through the use of Stump’s own stunning photography and shaded-relief maps, the book plots the routes taken by the early expeditions, from the 19th century pioneers who arrived in wooden ships through the Heroic Age of Exploration represented by Scott, Shackleton, and Amundsen to the modern era of scientific research. The Antarctic Sun Antarctic Sun: The Transantarctic Mountains is a place where you’ve worked on and off for 40 years. Why did you want write a book about the world’s least-known mountain range, and what were some of the challenges of writing a history of the Transantarctics? Edmund Stump: I feel it has been a great privilege to be able to work for so many years in the Transantarctic Mountains. I find the mountains to be incredibly beautiful. From very early on, I have fancied doing a picture book of the place. It is part ego, I suppose, and part genuinely wanting to share the place with others. A picture book needs a text, even if most people only look at the pictures, and at some point, I hit on doing a narrative of exploration as the context for the photos. The first challenge then was pairing as many of my photos as I could with places that the explorers had visited. My use of the shaded-relief, topographic maps to show the explorers’ routes developed late in the project, and the challenge there was to [use] Photoshop® [on] the digital images of the maps of all words, and to add names and routes with Adobe Illustrator®. This took many hours over many months. AS: What do you consider some of the key scientific discoveries that have come out of the Transantarctics? What have they revealed not just about the continent, but the geological history of the world? ES: Although by the late 1960s everyone was jumping on the plate-tectonic bandwagon, the discovery of Lystrosaurus [an ancestor to mammals that lived 250 million years ago] was very important [in] affirming the existence of [the supercontinent] Gondwanaland prior to its breakup and continental drift. Starting in the early 1990s, there was a big push internationally to reconstruct the supercontinent of Rodinia, the one that broke up about 750 million years ago before coming back together in Gondwanaland and Pangaea. Because of Antarctica’s central position in Rodinia, this research was important beyond the continent. The history of glaciation in Antarctica has been a longstanding research topic that continues to have profound implications for the global evolution of climate on timescales varying from thousands to tens of millions of years. AS: You mention in the beginning of the book that your personal heroes of Antarctic exploration are the three members of geologist Quin Blackburn’s party that traversed to the head of Scott Glacier during Admiral Byrd’s second expedition in the early 1930s. In fact, you suggested the name Gothic Mountains for a group of mountains first visited by Blackburn’s team in the region in 1934. What is it about this particular explorer that has captured your admiration? ES: For starters, Quin Blackburn was a geologist, out there doing what geologists do, collecting samples, measuring sections, and as all the early parties did, surveying. What I admire most about the Blackburn party is the competency with which they did their traverse. Byrd had taken a page out of Amundsen’s playbook in terms of driving dogs and eating dogs. Each member of the party, Blackburn, Stuart Paine, and Richard Russell, had a team at the start. They traversed really gnarly crevasse fields, especially in the middle stretch of Scott Glacier. They suffered under relentless katabatic winds. They discovered what, to my money, is the most beautiful section of the TAM. They went about their business without fanfare, and with no aggrandizement afterwards. They came back from the traverse weighing more than they did when they left. These guys really had exploration down pat.

Photo Credit: Peter Rejcek/Antarctic Photo Library

A helicopter flies over the central Transantarctic Mountains field camp where Ed Stump served as chief scientist in 2010-11.

I did indeed name the Gothic Mountains, following the ’80-’81 field season, when we mapped and collected [samples from] them. I chose the name to be of the same theme as the name Organ Pipe Peaks, which was Quin Blackburn’s name, and the only descriptive name for his entire traverse of Scott Glacier. It wasn’t until some years later that I realized that both Blackburn and Stuart Paine had described them as having the appearance of Gothic cathedrals in their journals. … For sure, the name is apt. AS: You had an opportunity to return to the Transantarctic Mountains as chief scientist of a large field camp near the Beardmore Glacier for the 2010-11 field season, exactly 40 years after your first trip down to the Ice. The technologies have changed. The science questions have changed. My sense from talking with you in Antarctica is that your passion and enthusiasm for the continent and its mountains hasn’t changed. What’s the endearing attraction after four decades? ES: It is the place itself that has kept calling me back. Antarctica is such pristine wilderness. To me being in mountains, any mountains, lifts my spirit. But the Transantarctic Mountains are different by virtue of their being polar. Devoid of vegetation and dirt, there is a purity to the landscape that transcends all others. Add to that the ice in all its graceful and chaotic forms, and you have more beautiful country than can be explored in a lifetime. |