|

The next generationDescendants of Scott and Amundsen find their way to AntarcticaPosted January 20, 2012

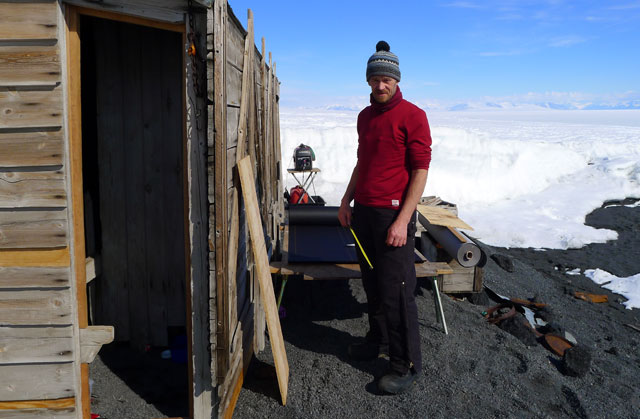

A century ago, Briton Robert Falcon Scott and Norwegian Roald Amundsen raced to be the first people to reach the geographic South Pole, one of the last great feats of polar exploration. Today, two men with similar names are in Antarctica during the centennial season, including an Amundsen at the South Pole. Actually, make that Amundson with an “o.” Kristopher Amundson is working for a year as the IT network engineer at the South Pole Station The name was changed somewhere in the Midwest, according to Amundson. Apart from that, he doesn’t have much additional information about his exact familial relationship to Roald Amundsen, who was the first to reach the South Pole on Dec. 14, 1911, with four companions. “From the family standpoint, it makes a pretty boring story,” says Amundson, 33, who was born and raised in Portland, Ore. Following in Scott's footstepsFalcon Scott will spend more than a month in Antarctica, but far from the South Pole, working as a restoration carpenter to conserve the expedition base from which his famous grandfather launched his trek to the South Pole on Nov. 1, 1911. Built in 1910, the wooden building at Cape Evans on Ross Island is one of several historic structures in the region that the Antarctic Heritage Trust Falcon Scott, only grandson of Capt. Robert F. Scott, grew up aware of the stories about his famous grandfather. But daily life revolved around his father’s career. Sir Peter Markham Scott was a famous conservationist and a founder of the World Wildlife Fund, as well as several wetlands bird sanctuaries in Britain. Peter Scott was only two years old when his father died, along with four countrymen, as they struggled, starving and weak, back from the South Pole. In a last letter to his wife, Capt. Scott advised her to “make the boy interested in natural history if you can; it is better than games.” The mantle of the Scott family’s legacy in Antarctica eventually fell to the 57-year-old Falcon Scott. “I think it started to become more a part of my life with the Discovery [expedition] centenary, which took place in 2001,” he says. The British National Antarctic Expedition of 1901-1904 Falcon Scott first visited the Ice in 1994, as a tourist aboard a cruise ship, which briefly stopped at Ross Island for a few hours. The visit didn’t include a stop at the Cape Evans site. “It was my wish to come back and have a more realistic experience of the Antarctic,” Falcon Scott says. A self-taught builder by trade, Falcon Scott applied for a job as a conservation carpenter several years ago with the Trust. This year he got his wish. “It’s really amazing. I’m completely overjoyed by the whole thing. It’s so stunning here,” he says by phone while standing on the volcanic rock beach near the hut in early January, a week before the day 100 years ago when Capt. Scott and his crew reached the South Pole on Jan. 17, 1912. “It was very emotional walking in. I didn’t expect it. I thought it would be very mechanical walking in,” he says of the moment he first entered the building, which his fellow conservators had restored to its original condition for him to see. “It brought a tear to my eyes. … It was a very special time. I’ll never forget it.” The Pole but under very different circumstancesKristopher Amundson would probably say the same thing. He had originally considered a much shorter trip to the South Pole versus the yearlong contract he signed to work at the bottom of the world. He and his friend, Austin Putnam, had conceived of the idea of visiting for a few days as tourists for the centennial celebration held on Dec. 14, 2011, which included a ceremony presided over by Norwegian Prime Minister Jens Stoltenberg. [See previous article — South Pole anniversary: Norwegian prime minister visits bottom of the world to honor Amundsen.]

Photo Credit: Peter Rejcek

The Dec. 14, 2011, ceremony marking the 100th anniversary of Roald Amundsen's arrival at the South Pole.

But such trips cost tens of thousands of dollars. He mentioned the dilemma to a stateside co-worker, Carla Appel, who coincidentally, had previously worked a few years earlier in the IT department at South Pole. It was a eureka sort of moment: “Why not get paid to go down there for the centennial,” Amundson says, adding that Appel left her job at the same company and returned to the South Pole to work as an IT systems administrator. “It was a weird coincidence, happenstance, alignment of planets,” Amundson says. The opportunity to meet the Norwegian prime minister and take part in the outdoor centennial anniversary will doubtless be a highlight of his time in Antarctica, he adds. But there are plenty of other things about his job that you don’t find in a typical IT environment. “Yup. I’m out in negative 25 running some Ethernet cable or putting network cables on snowmobile sleds to haul out to [remote areas],” Amundson says. “It’s just a little different.”

|

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsU.S. National Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |