|

RetirementErb prepares to step down as longest-serving director of NSF OPPPosted March 23, 2012

From a unique vantage point, spanning the end of one century and the beginning of another, Karl Erb, soon to step down as the longest-serving director of the Office of Polar Programs And that, he notes, is almost everything. It was the mid-1990s, and Erb was working for Neal Lane, then-director of the National Science Foundation (NSF)

In 1997, Augustine and his Blue Ribbon Panel In November 1998, Erb was appointed the director of the NSF’s Office of Polar Programs (OPP), where he would oversee construction of the new Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station “It’s going to be hard,” he says of retiring during a phone interview earlier this month. “I just enjoy doing it.” Erb took the helm of the USAP at a time of transition, and not just at the South Pole. The U.S. Navy, which had been the backbone of logistical support for U.S. research activities since the 1950s, was formally stepping aside. Civilian contractors had been slowly taking on the jobs once done by the Navy, while the New York Air National Guard Erb recalls the culture change that ensued, as regular tour-of-duty Navy personnel were replaced by part-time military men and women who were eager to share with others the adventures they had in Antarctica when they got back home. “That not only broadens support for the program, but it brings the program into a lot more houses,” Erb says. But it wasn’t just the culture that was changing. Capability and technology were also progressing. The U.S. Air Force “It has revolutionized the program,” Erb notes. Around the same time, the NSF started a new experiment with an old technology — the tractor traverse. It had been common in the 1950s to the 1960s to move materials and fuel across Antarctica’s vast icy desert using tractors and sleds. Now, the big-wheeled beasts of burden are back, carrying cargo and fuel between South Pole and McMurdo on a regular basis — reducing the USAP’s carbon footprint and freeing LC-130 flights for deep-field science support.

Photo Credit: Jean Varner/Antarctic Photo Library

The U.S. Air Force C-17 cargo airplane has helped revolutionize USAP logistics, according to Erb.

Photo Credit: Peter Rejcek/Antarctic Photo Library

Thousands of gallons of fuel are now transported by heavy tractors on the South Pole Operations Traverse.

“The traverse has been a focus and will be increasing in the future,” Erb says. On one of his first trips to the Ice, Erb says he toured the medical clinic at McMurdo Station and was surprised to see what looked like World War II-era X-ray equipment. Investments to update obsolete instruments and the advent of high-speed Internet has allowed surgeons in the United States to help doctors on the Ice with medical procedures, even things like appendectomies. “Now we have these links to world-class medical centers, which we can access through telemedicine. The expertise these medical centers [have] to help us with problems is tremendous,” he said. “That’s really a big change.” And the new world-class research station at the South Pole, dedicated in January 2008, has helped turn the bottom of the world into one of the top places to study the early universe and to try to observe the subatomic particles called neutrinos that whizz through the galaxy. In 1991, the NSF had established the Center for Astrophysical Research, a Science and Technology Center that ran for 10 years, laying the foundation for the explosion of large-scale projects that have come online in the last decade. Erb notes that the opportunities available to researchers at the South Pole Station are unique in the field of astrophysics. “A whole generation of astrophysicists achieved international renown in the very early stages of their careers,” he says. “In Antarctica, they can do science that they can’t do anywhere else, make discoveries, build careers and train students. It’s really very exciting.” An experimental nuclear physicist who served on the Yale University He noted that in taking up the directorship, there were those who observed that his background at first didn’t seem to quite mesh with glaciers and penguins, but Erb embraced the unfamiliar fields of research. And there’s one thing that all science projects share, he says, whether fitting an instrument on an accelerator or drilling through an ice sheet in the middle of Nowhere, Antarctica: “You have a plan and then you improvise around it.” Erb leaves just as Augustine has again been tapped to lead a Blue Ribbon Panel to shape the future of the Program for the next 20 years. The new report is expected to address things like transportation and deep-field support in an era when fuel costs and uncertainties around the United State’s icebreaker fleet are on the rise.

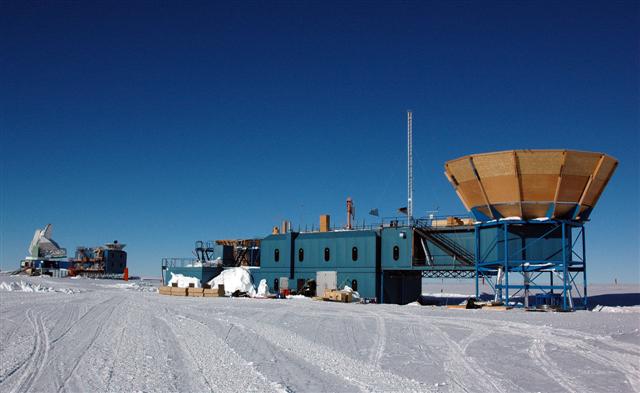

Photo Credit: Peter Rejcek/Antarctic Photo Library

The Dark Sector at the South Pole Station hosts a number of major astrophysical experiments.

Erb talks excitedly about the various possibilities under consideration by the panel, such as combining the new traverse capability with the Air Guard’s ski-equipped planes, stretching the logistical reach of the USAP into little-explored regions of the continent. He knows the future must include more alternative energy technologies, like the turbine wind farm built between McMurdo and New Zealand’s Scott Base He concedes that it’s tempting to remain at OPP just a little longer, to wander a little farther down that new roadmap being designed by the Blue Ribbon Panel. But then there are the years of missed art gallery shows and dormant hobbies like ham radio that take a backseat to what is a rewarding but demanding job, he says. Retirement promises its own awards. “The big thing for me is to choose how I use my time,” he says, promising that he will continue to remain involved and interested as polar research moves forward. “The frontier of science keeps expanding, and that’s really exciting, I think,” he says. “It stretches the imagination.” Kelly Falkner, deputy head of NSF OPP, will serve as the interim director of the program beginning on April 1. Prior to joining NSF in January 2011, Falkner was a professor in the College of Oceanic and Atmospheric Sciences at Oregon State University

|

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsU.S. National Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |