|

Launching new careersFormer USAP participants land spots on latest astronaut classPosted July 12, 2013

Antarctica is a huge continent — but it’s a relatively small world when it comes to those who have lived and worked on that frozen land. Yet Christina Hammock and Jessica Meir But they’ll get a chance to compare notes on their Antarctic experiences later this summer in Houston. Both were among the eight candidates selected to join the NASA astronaut corps “I think it’s awesome,” Hammock said of the inclusion of two USAP participants in the 21st astronaut class. Only 338 people have been selected since 1959, when NASA picked seven military pilots as the first U.S. astronauts.

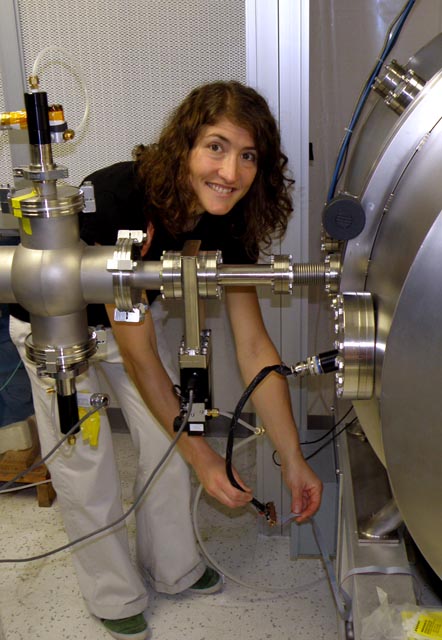

Photo Courtesy: Christina Hammock

Christina Hammock uses a particle accelerator to test an instrument for the NASA Juno Mission to Jupiter while working as an electrical engineer at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Lab.

“The USAP was an amazing program for me. It gave me a lot of opportunities,” Hammock said during a telephone interview from American Samoa, where she is the station chief for a NOAA “I think [Antarctica is] a great analog for the space program and for the whole concept of exploring the frontiers through science. It definitely gave me the confidence that I needed to move forward in my other jobs, and also to do the application [to NASA]. I feel like I owe so much to the USAP.” Hammock first worked at the Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station during the 2004-05 summer and then wintered over at the research facility in 2005. She was the cryogenics technician, a position that oversees the liquid helium supply that helps cool super-sensitive sensors on telescopes used to explore the universe from the bottom of the world. She was the first woman to hold that job, as well as the first woman at Palmer Station in 2006-07 to work as a research associate, an assignment that involves overseeing a variety of scientific experiments at the small marine research base. An electric engineer with graduate degrees from North Carolina State University “I wanted to be an astronaut my whole life,” said the 34-year-old. “I’ve always been drawn to science — any kind of science on the frontier has always fascinated me, and that’s where I wanted to be.” The posters on her wall as a kid were of two things — Antarctica and outer space. “I made a point of following those two things throughout my career,” Hammock said. She’s already had an opportunity to work with the U.S. space agency at the John Hopkins Applied Physics Lab “I’ve been really lucky that some of the things I’ve worked on have launched into space,” she said. Meir, 35, had similar dreams of far away places since she was at least five years old. “I think one of the things is just the feeling of wanting to be in space and looking back at Earth and seeing our whole planet and everything that you’ve ever known beneath you in its entirety like that,” she said from Boston, where she is currently an assistant professor at Harvard Medical School/Massachusetts General Hospital That childhood wish first sent her to NASA as early as an undergraduate at Brown University During her senior year at Brown, she and a few other students submitted a proposal for NASA’s Reduced Gravity Student Flight Opportunities program |

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsU.S. National Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |