|

Taking out the trashWaste Department helps keep the continent clean with a cool vibePosted May 30, 2014

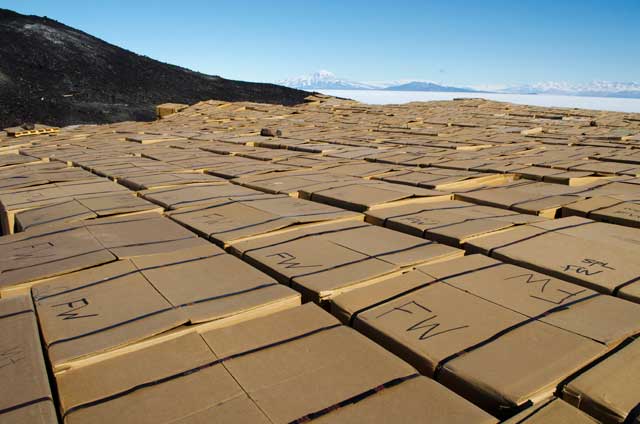

James VanMatre was kicking back on the Virgin Islands in the 1990s when he decided to give up the tropical sun for the extreme southerly latitudes of Antarctica, where he worked as a janitor his first season, then as a “trash man” the following austral summer. Nearly 20 years later, VanMatre is the supervisor of Waste Operations for the U.S. Antarctic Program (USAP) “I never thought I would be in the same business as my dad. That’s very strange,” he says. No stranger, perhaps, than the Herculean effort it takes to collect, package and ship hundreds of thousands of pounds of solid and hazardous waste from Antarctica every year. The United States, as a party to the international Antarctic Treaty system “We’re regulated by everyone,” says VanMatre, a young-looking 40-something who seems like he’d be more comfortable surfing waves than surfing through the piles of paperwork to satisfy regulations that literally stretch from one hemisphere to the next. But you won’t find a greater proselytizer about the world of waste than VanMatre, except perhaps his own tight-knit crew, most of whom work at McMurdo Station “Waste is an incredible community. I love working the Waste department – just really good friends. I laugh every day, most of the day,” enthuses Kate Fey, who has worked in the department all four of her seasons on the Ice. “It feels good to work for a department that is trying to keep Antarctica nicer,” adds Fey, also known around the station for her vocals fronting various McMurdo bands during her down time. “We do our part to reuse and recycle things so we’re not being wasteful.” The USAP boasts about a 65 percent recycle rate, much of it accomplished at the “grass roots” level by having the station residents sort their trash in dorms and offices. Lines of dumpsters, most made out of cardboard with wood lids, are found throughout the small research facility. Their contents – as well as trash from South Pole Station and field camps spread across the continent – eventually end up at the Waste Barn for additional processing. “Everything has to come off the continent in one way or another, so it makes sense not to have a huge pile of trash at the end of the season,” notes Julie Katch, lead recycling technician who joined the department last year. An architect by training, Katch worked several seasons in the USAP as a draftsperson. Both she and Fey had some experience in working in their city’s respective recycling program. However, most “wasties,” as the crewmembers are commonly called, don’t necessarily have waste management experience before they’re hired. The operation is too specialized, according to VanMatre, especially the hazardous waste component. Only the largest research universities in the United States produce the variety of hazardous waste – such as small amounts of radioactive materials used in labs – that the USAP must manage. “It’s a hard job to hire for,” VanMatre says, explaining that he tries to employ people who work well in teams, often drawing from departments where those on the lowest rungs have the toughest jobs but best attitudes. Those with a background on trail crews – strong and sturdy people accustomed to wielding chainsaws and shovels – usually fit in well with the department ethos. “Waste gives them a lot of independence. I need them to be self-starters and finish things without needing to be supervised,” VanMatre says. |

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsU.S. National Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |