Photo Credit: Peter Rejcek

|

MacOps operator Alyssa Hartson handles radio traffic while McMurdo Station communications supervisor

Shelly Campbell and operator Sage Asher discuss work schedules. MacOps monitors all field party communications.

|

MacOps, MacOps

McMurdo Station communications department serves as nerve center for fieldwork

By Peter Rejcek, Antarctic Sun Editor

Posted December 19, 2014

It’s mid-morning on a Tuesday, and bad weather has delayed or shut down most science operations around McMurdo Station. Helicopters and planes aren’t flying, which means most field parties aren’t moving around.

The only radio chatter is coming from “B-009,” the designation for a team of scientists monitoring Weddell seals on the sea ice. The group is on snowmobiles, preparing to depart its field camp.

The familiar call comes over the radio: “MacOps, MacOps, this is B-009 departing …”

McMurdo Communications Operations, better known as MacOps, is the nerve center for radio traffic between the research station and field parties as close as B-009 on the sea ice and as far as field camps hundreds of miles away.

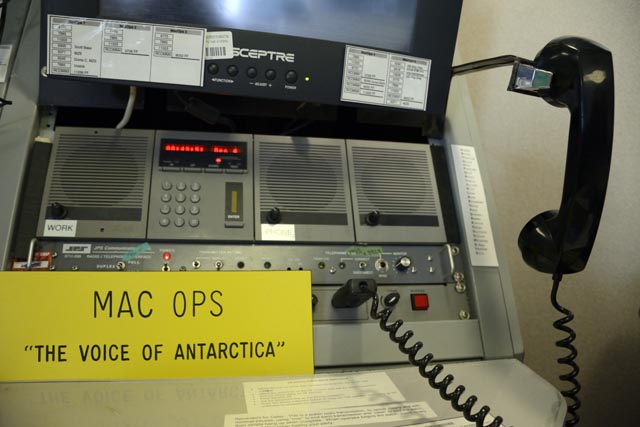

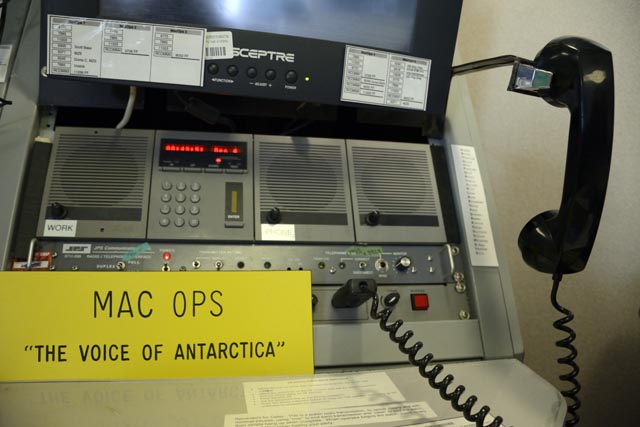

Photo Credit: Peter Rejcek

MacOps is known as the Voice of Antarctica.

For scientists in the field, MacOps serves as a lifeline in case of an emergency. But it’s more than that: It’s a crossroads of information when other sources about things such as weather and flights aren’t available. A constant stream of messages – as mundane as details on outgoing cargo or as personal as the birth of a niece back in the United States – pass through MacOps on a daily, an hourly basis.

“I really feel like we have our finger on the pulse – we know what is happening when,” says Sage Asher, one of four operators hired each austral summer to monitor the various lines of communication at MacOps, located in a two-story office complex simply known as Bldg. 165.

In a way, one can measure the heartbeat of the field season from the MacOps radio traffic. In the early weeks, most of the communication comes from field parties working on the nearby sea ice, such as biologists studying seals or atmospheric scientists analyzing air samples.

Soon helicopters start flying, ferrying people to the McMurdo Dry Valleys, a polar desert ecosystem studded with ice-covered lakes and wild geologic formations. Then planes begin taking scientists even farther afield, to glaciers and ice shelves and distant mountain peaks.

“It’s fun because we have different tempos depending on the time of season,” notes Shelly Campbell, McMurdo Station communications supervisor who started working in the U.S. Antarctic Program in 1996-97 as a general assistant. She joined MacOps the following year and – except for a five-year stint working in South Pole communications – has been in the department ever since.

Photo Credit: Peter Rejcek

Each field team gets a picture on the wall at MacOps.

At the peak of the field season – when the pulse is racing the fastest – MacOps can be tracking more than 30 field camps with 200 people or more at one time. There could be dozens of field check-ins and other radio and email traffic to monitor.

“It’s those days that make the job fun,” says Alyssa Hartson, a MacOps operator from Alaska in her second season in the department. “The hard days are when those camps don’t need anything and there’s not a lot of information coming through.”

Hartson experienced some slow days during the 2013-14 field season when the U.S. government shutdown curtailed the number of projects supported. The maximum population in the field at one time peaked at an eight-year low of 126 people. Field operations were at an exceptionally high tempo in 2010-11 with support of a large field camp in the Transantarctic Mountains. That year saw a max population of 335 people in 36 camps.

Field science begins to shrink just after it swells to the maximum extent, as sea ice melts, forcing researchers to pull back to McMurdo Station. Helicopters wind down by the end of January and big field camps in remote areas are broken down and winterized.

Even the types of communications used by those in the field follows this rhythm. Most nearby communication with MacOps is by VHF (very-high-frequency) radio from groups operating on the sea ice. Increasing distance requires either high-frequency radio communications – bouncing radio signals off the Earth’s ionosphere – or Iridium satellite phones.

Photo Credit: Peter Rejcek

A map of the McMurdo Dry Valleys shows some of the field camps monitored by MacOps.

“It’s interesting to go through these phases,” says Asher, also from Alaska, who worked many years in the high-tempo restaurant industry that helped prepare her to deal with a daily barrage of communiques.

Operator Carey Collins has worked on and off in MacOps for nearly two decades, including several seasons in the now-defunct MacRelay. She recalls the days when racks lining one wall in an adjoining room were filled with analog instruments that provided functions now served by other technologies.

A close cousin of MacOps, MacRelay operated in the days before Internet and satellite communications became so ubiquitous. Data were sent over HF radio. The “static” was then translated by computer into a readable message.

“It just seems so long ago,” Collins says. “We did very intensive support for the Coast Guard cutters when they came down because the satellite coverage for ships was spotty once they got far enough south to cut ice.”

MacOps may be more high-tech these days – with sending text messages through Iridium, a constellation of about 70 low-orbiting satellites – but the team insists on providing a personal touch.

“It is more customer-service oriented than I thought it would be coming into the job,” Asher says. “I think we do have the opportunity to give it a bit more personality, and people really respond to it.”

Photo Credit: Peter Rejcek

MacRelay is no longer a functioning part of the McMurdo Station communications infrastructure.

Each research team must visit MacOps before deploying to the field for a communications brief. That gives both groups time to meet. One MacOps tradition is to shoot a photo of each team, which is pinned on the wall of the communications center. This year, MacOps reciprocated with a photo of their own.

Microbiologist Jill Mikucki, returning from three weeks working atop Taylor Glacier in the McMurdo Dry Valleys, raved about the support she and her team receive from MacOps.

“They’re a lifeline. They’re entertainment,” Mikucki says.

For example, operator Gracie Cole has been known to read the horoscope to field teams over HF radio. This is Cole’s first year in the department, after working several summers as part of the station’s dish-washing crew, as well as two winters at McMurdo Station in the Recreation department and Berg Field Center, respectively.

“I wanted to be in a position where I was more directly involved with mission-critical operations, either with science or direct support. That appealed to me,” Cole says. “You get a better idea of what goes into different aspects of our program.”

Learning about the discoveries as they’re happening has been one of the exciting things for Collins. “I love the fact that we support science directly. That’s the thing that I always thought was great about MacOps and has kept me in the department all these years,” she says. “It adds a human side to the achievements that you may read about later.

“We get to be part of that.”